This is “Group Decision-Making”, section 11.2 from the book An Introduction to Group Communication (v. 0.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

11.2 Group Decision-Making

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Define decision-making and distinguish between decision-making and problem-solving.

- Describe five methods of group decision-making.

- Identify six guidelines for consensus decision-making.

- Define autocratic, democratic, and participative decision-making styles and place them within the Tannenbaum-Schmidt continuum.

Life is the sum of all your choices.

Albert Camus

Simply put, decision-makingThe process of choosing among options and arriving at a position, judgment, or action. is the process of choosing among options and arriving at a position, judgment, or action. It usually answers a “wh-” question—i.e., what, who, where, or when?—or perhaps a “how” question.

A group may, of course, make a decision in order to solve a problem. For instance, a group of students might discover halfway through a project that some of its members are failing to contribute to the required work. They might then decide to develop a written timeline and a set of deadlines for itself if it believes that action will lead them out of their difficulty.

Not every group decision, however, will be in response to a problem. Many decisions relate to routine logisticalRoutine in nature (applicable to fundamental elements and considerations of how an organization or process works). matters such as when and where to schedule an event or how to reach someone who wasn’t able to make it to a meeting. Thus, decision-making differs from problem-solving.

Any decision-making in a group, even about routine topics, is significant. Why? Because decision-making, like problem-solving, results in a change in a group’s status, posture, or stature. Such change, in turn, requires energy and attention on the part of a group in order for the group to progress easily into a new reality. Things will be different in the group once a problem has been solved or a decision has been reached, and group members will need to adjust.

Methods of Reaching Decisions

Research does indicate that groups generate more ideas and make more accurate decisions on matters for which a known preferred solution exists, but they also operate more slowly than individuals.Hoy, W.K., & Miskel, C.G. (1982). Educational administration: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.). New York: Random House. Under time pressure and other constraints, some group leaders exercise their power to make a decision unilaterallyDetermined or executed by one person alone.—alone—because they’re willing to sacrifice a degree of accuracy for the sake of speed. Sometimes this behavior turns out to be wise; sometimes it doesn’t.

Assuming that a group determines that it must reach a decision together on some matter, rather than deferring to the will of a single person, it can proceed according to several methods. Parker and HoffmanParker, G., & Hoffman, R. (2006). Meeting excellence: 33 tools to lead meetings that get results. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass., along with Hartley and DawsonHartley, P., & Dawson, M. (2010). Success in groupwork. New York: St. Martin’s Press., place decision-making procedures in several categories. Here is a synthesis of their views of how decision-making can take place:

-

“A plop.”

A group may conduct a discussion in which members express views and identify alternatives but then reach no decision and take no action. When people go their own ways after such a “plopA discussion in which members of a group express views and identify alternative but reach no decision and take no action.,” things sometimes take care of themselves, and the lack of a decision causes no difficulties. On the other hand, if a group ignores or postpones a decision which really needs attention, its members may confront tougher decisions later—some of which may deal with problems brought about by not addressing a topic when it was at an early stage.

-

Delegation to an expert.

A group may not be ready to make a decision at a given time, either because it lacks sufficient information or is experiencing unresolved conflict among members with differing views. In such a situation, the group may not want to simply drop the matter and move on. Instead, it may turn to one of its members who everyone feels has the expertise to choose wisely among the alternatives that the group is considering. The group can either ask the expert to come back later with a final proposal or simply allow the person to make the decision alone after having gathered whatever further information he or she feels is necessary.

-

Averaging.

Group members may shift their individual stances regarding a question by “splitting the difference” to reach a “middle ground.” This technique tends to work most easily if numbers are involved. For instance, a group trying to decide how much money to spend on a gift for a departing member might ask everyone for a preferred amount and agree to spend whatever is computed by averaging those amounts.

-

Voting.

If you need to be quick and definitive in making a decision, voting is probably the best method. Everyone in mainstream American society is familiar with the process, for one thing, and its outcome is inherently clear and obvious. A majority voteA process of making a decision whereby the vote of more than half a group’s members are considered to be decisive. requires that more than half of a group’s members vote for a proposal, whereas a proposal subject to a two-thirds voteA process of making a decision whereby twice as many voters have to approve of a proposal than oppose it in order for the proposal to be accepted. will not pass unless twice as many members show support as those who oppose it.

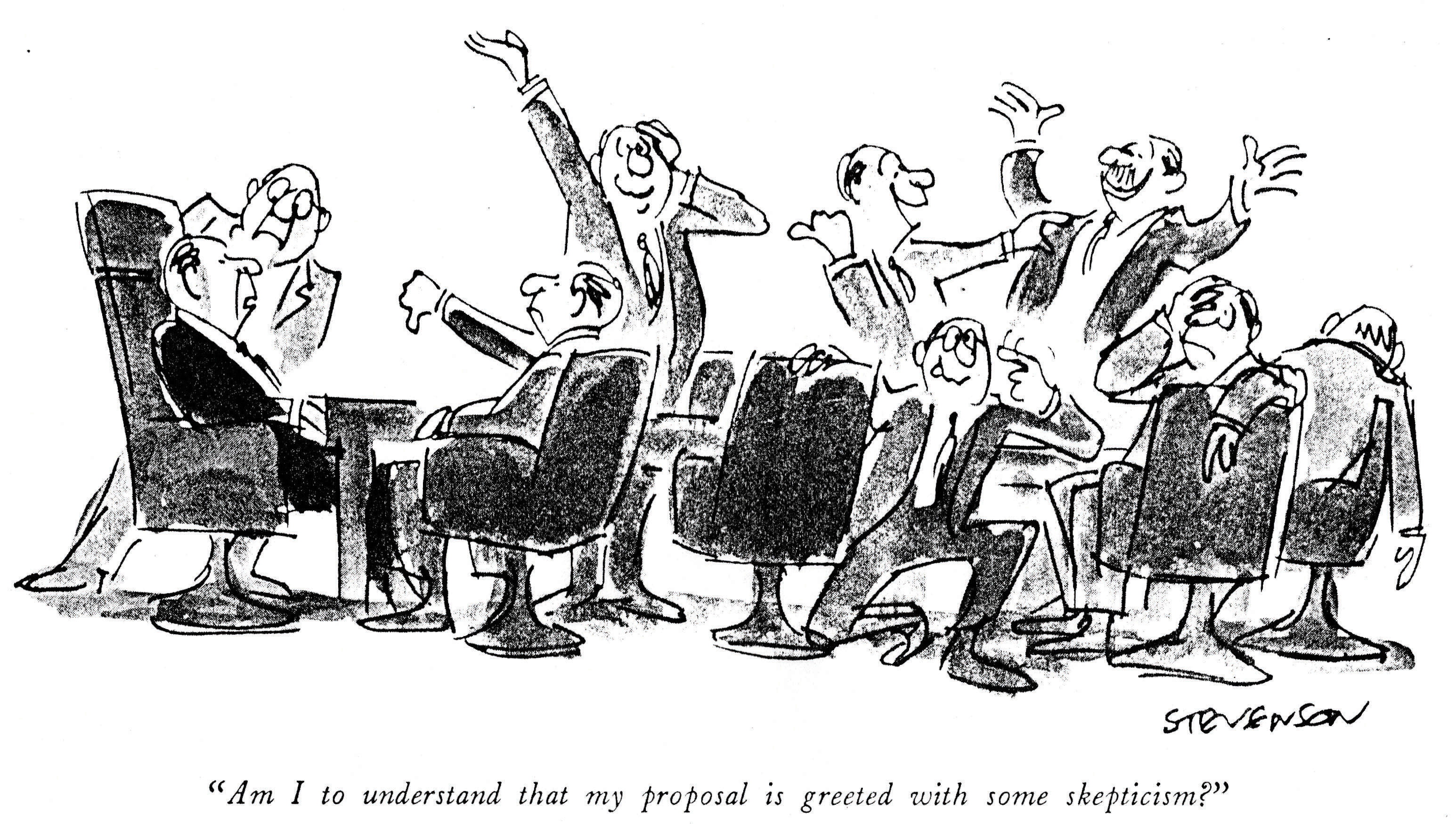

Voting is essentially a win/lose activity. You can probably remember a time when you or someone else in a group composed part of a strong and passionate minority whose desires were thwarted because of the results of a vote. How much commitment did you feel to support the results of that vote?

Voting does offer a quick and simple way to reach decisions, but it works better in some situations than in others. If the members of a group see no other way to overcome a deadlock, for instance, voting may make sense. Likewise, very large groups and those facing serious time constraints may see advantages to voting. Finally, the efficiency of voting is appealing when it comes to making routine or noncontroversial decisions that need only to be officially approved.

-

Consensus.

In consensus decision-making, group members reach a resolution which all of the members can support as being acceptable as a means of accomplishing some mutual goal even though it may not be the preferred choice for everyone. In common use, “consensus” can range in meaning from unanimity to a simple majority vote. In public policy facilitation and multilateral international negotiations, however, the term refers to a general agreement reached after discussions and consultations, usually without voting.“consensus”. (2002). In Dictionary of Conflict Resolution, Wiley. Retrieved from http://www.credoreference.com/entry/wileyconfres/consensus

Consensus should not be confused with unanimityA condition in which no one in a group has explicitly stated objections to a proposal or decision., which means only that no one has explicitly stated objections to a proposal or decision. Although unanimity can certainly convey an accurate perspective of a group’s views at times, groupthink also often leads to unanimous decisions. Therefore, it’s probably wise to be cautious when a group of diverse people seems to have formed a totally unified bloc with respect to choices among controversial alternatives.

When a consensus decision is reached through full interchange of views and is then adopted in good faithSeriously and honestly, as in a decision-making or conflict situation. by all parties to a discussion, it can energize and motivate a group. Besides avoiding the win/lose elements intrinsic to voting, it converts each member’s investment in a decision into a stake in preserving and promoting the decision after it has been agreed upon.

Guidelines for Seeking Consensus

How can a group actually go about working toward consensus? Here are some guidelines for the process:

First, be sure everyone knows the definition of consensus and is comfortable with observing them. For many group members, this may mean suspending judgment and trying something they’ve never done before. Remind people that consensus requires a joint dedication to moving forward toward improvement in and by the group.

Second, endeavor to solicit participation by every member of the group. Even the naturally quietest person should be actively “polled” from time to time for his or her perspectives. In fact, it’s a good idea to take special pains to ask for varied viewpoints when discussion seems to be stalled or contentious.

Third, listen honestly and openly to each group member’s viewpoints. Attempt to seek and gather information from others. Do your best to subdue your emotions and your tendency to judge and evaluate.

Fourth, be patient. To reach consensus often takes much more time than voting would. A premature “agreement” reached because people give in to speed things up or avoid conflict is likely later to weaken or fall apart.

Fifth, always look for mutually acceptable ways to make it through challenging circumstances. Don’t resort to chance mechanisms like flipping a coin, and don’t trade decisions arbitrarily just so that things come out equally for people who remain committed to opposing views.

Sixth, resolve gridlock earnestly. Stop and ask, “Have we really identified every possible feasible way that our group might act?” If members of a group simply can’t agree on one alternative, see if they can all find and accept a next-best option. Then be sure to request an explicit statement from them that they are prepared to genuinely commit themselves to that option.

One variation on consensus decision-making calls upon a group’s leader to ask its members, before initiating a discussion, to agree to a deadline and a “safety valve.” The deadline would be a time by which everyone in the group feels they need to have reached a decision. The “safety valve” would be a statement that any member can veto the will of the rest of the group to act in a certain way, but only if he or she takes responsibility for moving the group forward in some other positive direction.

Although consensus entails full participation and assent within a group, it usually can’t be reached without guidance from a leader. One college president we knew was a master at escorting his executive team to consensus. Without coercing or rushing them, he would regularly involve them all in discussions and lead their conversations to a point at which everyone was nodding in agreement, or at least conveying acceptance of a decision. Rather than leaving things at that point, however, the president would generally say, “We seem to have reached a decision to do XYZ. Is there anyone who objects?” Once people had this last opportunity to add further comments of their own, the group could move forward with a sense that it had a common vision in mind.

Consensus decision-making is easiest within groups whose members know and respect each other, whose authority is more or less evenly distributed, and whose basic values are shared. Some charitable and religious groups meet these conditions and have long been able to use consensus decision-making as a matter of principle. The Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers, began using consensus as early as the 17th century. Its affiliated international service agency, the American Friends Service Committee, employs the same approach. The Mennonite Church has also long made use of consensus decision-making.

Decision-Making by Leaders

People in the business world often need to make decisions in groups composed of their associates and employees. Take the case of a hypothetical businessperson, Kerry Cash.

Kerry owns and manages Wenatcheese, a shop which sells gourmet local and imported cheese. Since opening five years ago, the business has overcome the challenge of establishing itself and has built a solid clientele. Sales have tripled. Two full-time and four part-time employees—all productive, reliable, and customer-friendly—have made the store run efficiently and bolstered its reputation.

Now, with Christmas and the New Year coming, Kerry wants to decide, “Shall I open another shop in the spring?” Because the year-end rush is on, there’s not a lot of time to weigh pros and cons.

As the diagram indicates, many managers in Kerry’s situation employ two means to make decisions like this: intuition and analysis. They’ll feel their gut instinct, analyze appropriate financial facts, or do a little bit of both.

Unfortunately, this kind of dualistic decision-making approach restricts an individual leader’s options. It doesn’t do justice to the complexity of the group environment. It also fails to fully exploit the power and relevance of other people’s knowledge.

Figure 11.1 Intuition-Analysis

Too much feeling may produce arbitrary outcomes. And, as the management theorist Peter Drucker observed, too much fact can create stagnation and “analysis paralysisAn overload of information beyond what is needed, leading to an inability to make a decision.”: “(A)n overload of information, that is, anything much beyond what is truly needed, leads to information blackout. It does not enrich, but impoverishes.”Drucker, P.F. (1993). The effective executive. New York: Harperbusiness.

Fortunately, a couple of authorities wrote an article in 1973 which can help members of groups assess and strengthen the quality of their decision-makingTannenbaum, R., & Schmidt, W. (1973, May-June). How to choose a leadership pattern. Harvard Business Review, 3–11.. Robert Tannenbaum and Warren Schmidt were those authorities. Their article so appealed to American readers that more than one million reprints eventually sold.

The Tannnenbaum-Schmidt Continuum

Kerry Cash, wondering whether to open another Wenatcheese outlet, can refer to the Tannenbaum-Schmidt model in Table 11.2 "Tannenbaum-Schmidt Continuum" to identify a spectrum of ways to resolve the question:

Table 11.2 Tannenbaum-Schmidt Continuum

| Autocratic | Democratic | Participative | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manager makes decision and announces it | Manager sells decision | Manager presents ideas and invites questions | Manager presents tentative decisions subject to change | Manager presents problem, gets suggestions, and makes decision | Manager defines limits asks group to make decision | Manager permits subordinates to function within limits defined by superior |

Let’s take a look at the components of this continuum, from left to right. First, we have two autocratic options:

- OPTION ONE: Pure announcement. “All right, folks, I’ve decided we’re going to open a new shop in Dryden over Memorial Day weekend.”

- OPTION TWO: “Selling”. “I’d like us to open a new shop in Dryden. I have five reasons. Here they are…”

Next, three democratic options are available:

- OPTION THREE: Presentation with questions. “I’ve decided we’ll open a new shop in Dryden. What would you like to know about the plan?”

- OPTION FOUR: Tentative decision. “I want to open a new shop in Dryden. Do you have any observations or questions about this possibility?”

- OPTION FIVE: Soliciting suggestions. “I think we’re in a position to open a new shop. Dryden seems like the best location, but I’d also consider Cashmere or Leavenworth or Okanogan. I’ll decide which way to go after you give me your thoughts.”

Finally, two participative kinds of approaches present themselves:

- OPTION SIX: Limited group autonomy. “I want to open a new shop in either Dryden, Cashmere, or Leavenworth sometime between Easter and Independence Day. Talk it over and let me know what we should do.”

- OPTION SEVEN: Full group autonomy. “I’m willing to establish a new shop if you’d like. Let me know by two weeks from now whether you want to do that, and if so, where and when.”

Of course, many decisions embody more complications and include more details than Kerry Cash’s. Some are related to people: Shall we bring more people into the group? If we do, how many should be full-fledged and how many should be temporary or provisional? Or do we need to reduce our number of members?

Other decisions depend on financial variables and constraints: Can we trust the economy enough to invest in new equipment? Do we have time to develop and promote any new ideas?

The Tannenbaum-Schmidt model doesn’t tell us how to choose between its own options. Tannenbaum and Schmidt, however, did offer some advice on this score. These are some topics they suggested that leaders address as they decide where to position themselves on the continuum:

- THE ORGANIZATION. What kind is it? Is it a new, or is it relatively solid and secure?

- THE PEOPLE. How mature are they? How experienced? How motivated?

- THE PROBLEM OR DECISION. How intricate is it? What kind of expertise is required to solve it?

- TIME. What deadlines, if any, do we face? Is there enough time to involve as many people as we’d like?

Robert Tannenbaum died in 2003 after more than 50 years as a consultant, an academic, and a writer for businesses and organizations. Warren Schmidt lives on as an emeritus professor in the School of Policy, Planning, and Development at the University of Southern California.

Intel Corporation actually identifies in advance of its meetings the kind of decision-making that will be associated with each question or topicMatson, E. (1996, April-May). The seven sins of deadly meetings. Fast company, 122.. The four categories it uses resemble some of the components of the Tannenbaum/Schmidt model, as follows:

- Authoritative (the leader takes full responsibility).

- Consultative (the leader makes a decision after weighing views from the group).

- Voting.

- Consensus.

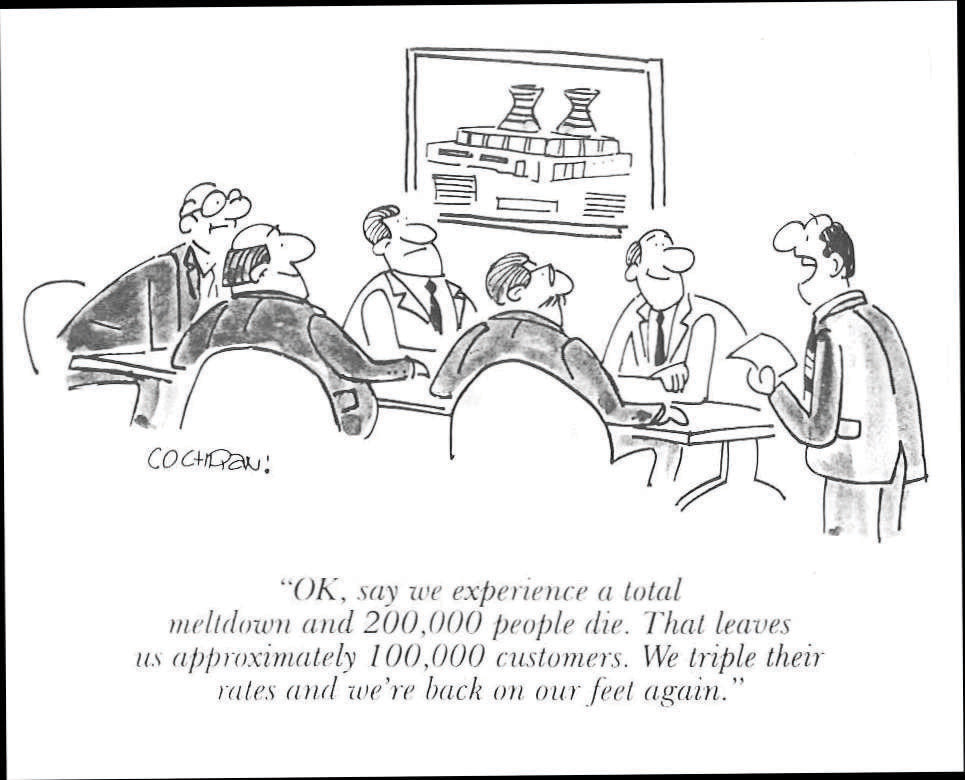

Once you’ve reached a decision, take a few steps back. Ask yourself, “Is it truly consistent with our group’s values, or was it perhaps simply a technocraticBased primarily or exclusively on scientific data and technical information rather than on human considerations. outcome: i.e., procedurally proper but devoid of empathy and human understanding? Throughout history, many a group’s decision reached “by the book” later caused dissension, disappointment, or even dissolution of the group itself.

Key Takeaways

- Groups may choose among several methods of decision-making, including consensus, depending on their circumstances and the characteristics of their leaders and members. Making decisions which are consistent with the group’s values is of paramount importance.

Exercises

- Think of major decisions made in the last couple of years by two groups you’re a part of. Which method from this section did the groups use in each case? Which of the decisions are you more satisfied with now? Why? To what degree do you feel the decision-making methods the groups used fit the circumstances and the characteristics of the groups themselves?

- Tell a classmate about a decision that a group you’re part of needs to make shortly. Ask the classmate for his/her advice on which decision-making method the group should employ.

- A major hesitation raised by some people with respect to consensus decision-making is that it requires much more time than voting or other direct methods. In what kind of situation would you be, or have you been, willing to invest “as much time as it takes” to reach consensus in a group?

- If you were compelled to make every decision either totally by intuition or totally by analysis, which would you choose? On the basis of what experience or value do you feel this way? If you could choose to have every group leader around you make decisions by only one of the two methods, which would you prefer, and why?