This is “Effective Motivation Strategies”, section 9.3 from the book An Introduction to Group Communication (v. 0.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

9.3 Effective Motivation Strategies

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Acknowledge the value of trust among group members.

- Identify four effective motivation strategies.

No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.

Althea Gibson

In the first parts of this chapter we’ve discussed several theories of motivation. Some of the theories laid greatest emphasis on identifying factors that attract people to become motivated, whereas others focused on how the factors interact to produce motivation. What we haven’t answered yet, however, is a very important question: “How can we get a person to acquire motivation and actually act on it?”

At first glance, we might think this is a very easy question to answer. After all, we see people acting in ways that other people want them to every day. What if getting a person motivated and having the person do something on the basis of that motivation is a really simple matter? What if all we need to do is follow a few steps, like these, which are based on the behaviorist concepts of B.F. Skinner that we touched on earlier?

- Tell the person what you want him or her to do in measurable terms. Explain specifically what you have in mind.

- Measure the person’s current level of performance. Determine whether and how well the person is doing the activity in question.

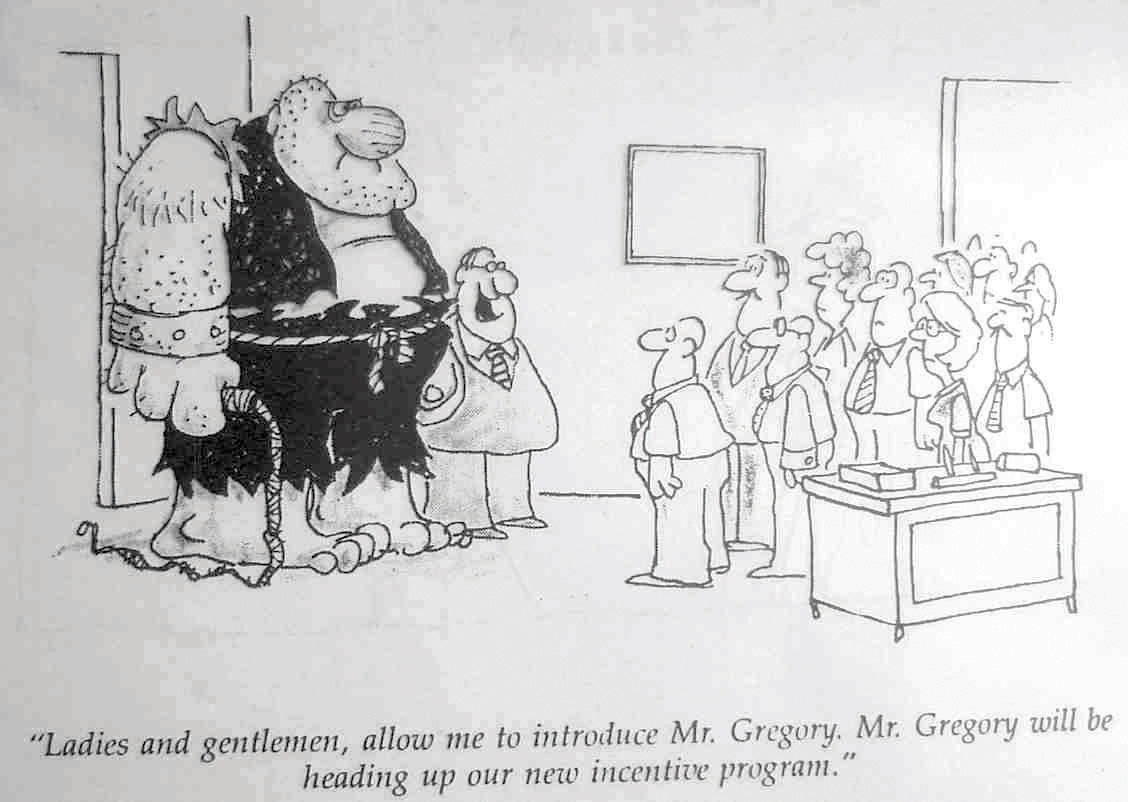

- Let the person know what kind of reward he or she will receive if he or she does what you’ve asked. Be sure to make clear that the reward will follow if the performance goal is achieved.

- When the person does what you’ve asked, give the person the reward you said you would.

In the world of business, some organizations have tried to follow exactly these four behaviorist steps to motivate employees. BurkeBurke, W.W. (2011). Organization change (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. and KelloKello, J.E. (2008). Reflections on I-O psychology and behaviorism. In N. K. Innis (ed.), Reflections on adaptive behavior: Essays in honor of J.E.R. Staddon (pp. 291–313). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. wrote that in the 1970s Emery Air Freight was one of the first and most publicized examples. As it turned out, Emery found that performance by its employees increased and that costs to the company declined by approximately $3 million over a three-year period.Schulz, D., & Schulz, S.E. (2002). Psychology and work today (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

But things are more complicated than this in other places, aren’t they? Emery Air Freight was in the business of processing packages, and that’s a pretty cut-and-dried industrial procedure. College students and church members and people in community organizations or not-for-profit agencies are involved in broader, more complex activities than those that many air freight workers or other employees in commercial enterprises perform.

Requirements for Motivating Action

According to behaviorism, it’s unnecessary to pay attention to people’s interior statesThoughts, feelings, and sentiments within people. (Behaviorists hold that motivation can be explained and promoted without reference to interior states). in order to motivate them to do things. Emery Air Freight’s approach, with its predetermined regimen of consequences for its employees’ behavior, was consistent with this belief.

Most theorists today, however, believe that people need to undergo certain mental processes and reach certain mental states in order to take any particular action. Specifically, for people to be motivated to act the way someone else wants them to, they first need to possess the skills and abilities required to accomplish the action. If they have those skills and abilities, they also need to know what the other person wants them to do, how to do it, and what will happen if they do it.

In a group, having a designated leader propose that people act in a certain way can often be helpful. This will depend on the structure and mood and purpose of the group, however.

If you’re part of a team of students that has been assigned a project, for instance, you might not decide to choose a leader. Instead, you and the other members may want to motivate each other by discussing your needs and options as equals to see what ideas and directions bubble up spontaneously.

No matter who is trying to motivate whom to act, one final consideration should be taken into account. Motivation, as we noted in chapter 4, is at least partly determined by whether people trust each other.

What if you think someone’s primary reason for asking you to do something in a group is that the person hopes to gain personally from what you do? If that’s the case, you’re not very apt to be motivated. If the person seems to care about you genuinely, on the other hand, you’re more likely to go along with his or her suggestions.

Motivation Strategies

Let’s take a look at four strategies for motivating people in groups. Three of the strategies are based in longstanding organizational research, whereas one is a broader approach to motivation in general.

Based on their study of research in groups, Hoy and MiskelHoy, W.K., & Miskel, C.G. (1982). Educational administration: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.). New York: Random House. contended that taking the following steps will lead people to be motivated:

- Allow all members of the group to set goals together, rather than imposing goals upon them. Research indicates that people who get to participate in developing their own goals become more satisfied during the performance of their tasks than those who don’t. If your student group is supposed to deliver a presentation together, you should all meet at the start of your assignment and decide what you plan to accomplish.

- Establish goals which are specific. Broad or unclear goals are unlikely to cause people in a group to focus their attention and energy well. Instead of saying, “Let’s all pitch in and give our presentation 10 days from now,” it’s better to decide which person will talk about which subjects in the presentation, for how many minutes, and with how many handouts or projected images.

- Establish the highest possible goals. You’ve perhaps heard the adage “Shoot for the moon; even if you miss, at least you’ll hit the stars.” The saying isn’t astronomically accurate, of course, since the stars are a lot farther away than the moon. The principle is a good one, though, since research shows that the more difficult the goals, the more effort people will put into achieving them, as long as they accept the more difficult goals in the first place.

Hoy and Miskel contended that these three strategies tend to reinforce one another. In particular, they wrote, members of a group who are allowed to participate in setting its goals may not necessarily perform at a higher level than those who aren’t, but they’re likely to set higher goals for themselves than people who have goals imposed upon them. Thus, at least indirectly, the outcomes of their work may be better for the group.

In his book Intrinsic Motivation at Work, Kenneth Thomas wrote about a fourth strategy for motivating people: developing rewards tentatively and being prepared to change them as circumstances dictate. Personal goals and desires may shift with time, he contended, and people also sometimes have multiple and even conflicting goals. Sometimes a person who initially was enthusiastic about working on a task might say, “My get-up-and-go got up and went.”

Students working on a team project, for example, may go through a cycle of changing personal goals. When they first get together, they may want more than anything else to minimize the time they spend on the project. Later, they might start to care much more about receiving a good grade—or about building relationships among themselves, or about something else entirely. To motivate them requires flexibility.

Key Takeaway

Allowing group members to set specific, challenging goals and being willing to modify those goals as circumstances change is likely to motivate them to act in a desired manner.

Exercises

- Think of a group you’ve been a part of in which trust among its members was strong. How did you know that the trust existed? What caused it to develop? How did its presence affect the group’s motivation?

- Some people might claim that part of leadership is to set goals for a group, not to ask people to set its goals together. If you were ever in a group whose leader established its goals, how do you feel that influenced the members’ attitudes and motivation?

- In what ways do you feel a group’s motivation might benefit if its members operated without a designated leader? In what ways might its motivation suffer?