This is “Middle English Literature”, chapter 1 from the book An Introduction to British Literature (v. 0.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 1 Middle English Literature

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

1.1 Introduction to Middle English Literature: The Medieval World

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Compare and contrast the comitatus organization of Old English society with medieval feudalism.

- Identify the three estates of medieval society and appraise their function.

- Assess the influence of the Church on the literature of the Middle Ages.

- Understand the correlation between the Church and the concept of chivalry in the Middle Ages.

- Recognize types of religious literature of the Middle Ages, including medieval drama.

- Assess the impact of Caxton’s printing press on the Middle English language and literature.

The world about which Chaucer wrote was a very different world from that which produced Beowulf. Developments in language, new structures in society, and changes in how people viewed the world and their place in it produced literature unlike the heroic literature of the Old English period.

Language

After the Norman Conquest in 1066, Old English was suppressed in records and official venues in favor of the Norman French language. However, the English language survived among the conquered Anglo-Saxons. The peasant classes spoke only English, and the Normans who spread out into the countryside to take over estates soon learned English of necessity. By the 14th century, English reemerged as the dominant language but in a form very different from Anglo-Saxon Old English. Writers of the 13th and 14th centuries described the co-existence of Norman French and the emerging English now known as Middle English.

A medieval university from a 13th-century illuminated manuscript.

Society

In the Middle Ages, the king-retainer structure of Anglo-Saxon society evolved into feudalisma method of organizing society consisting of three estates: clergymen, the noblemen who were granted fiefs by the king, and the peasant class who worked on the fief, a method of organizing society consisting of three estates: clergymen, the noblemen who were granted fiefs by the king, and the peasant class who worked on the fief. Medieval society saw the social order as part of the Great Chain of Beingthe metaphor used in the Middle Ages to describe the social hierarchy believed to be created by God, the metaphor used in the Middle Ages to describe the social hierarchy believed to be created by God. Originating with Aristotle and, in the Middle Ages, believed to be ordained by God, the idea of Great Chain of Being, or Scala Naturae, attempted to establish order in the universe by picturing each creation as a link in a chain beginning with God at the top, followed by the various orders of angels, down through classes of people, then animals, and even inanimate parts of nature. The hierarchical arrangement of feudalism provided the medieval world with three estates, or orders of society: the clergy (those who tended to the spiritual realm and spiritual needs), the nobility (those who ruled, protected, and provided civil order), and the commoners (those who physically labored to produce the necessities of life for all three estates). However, by Chaucer’s lifetime (late 14th century), another social class, a merchant middle class, developed in the growing cities. Many of Chaucer’s pilgrims represent the emerging middle class: the Merchant, the Guildsmen, and even the Wife of Bath.

Philosophy

The Church

The most important philosophical influence of the Middle Ages was the Church, which dominated life and literature. In medieval Britain, “the Church” referred to the Roman Catholic Church.

Canterbury Cathedral.

Although works such as Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales reveal an exuberant, and often bawdy, sense of humor in the Middle Ages, people also seemed to have a pervasive sense of the brevity of human life and the transitory nature of life on earth.

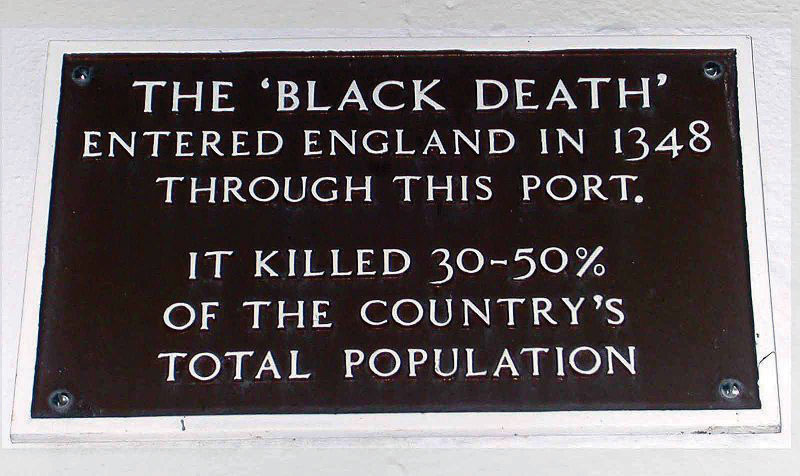

Plaque in Weymouth, England.

Outbreaks of the plague, known as the Black Death, affected both the everyday lives and the philosophy of the Middle Ages. It was not unusual for the populations of entire villages to die of plague. Labor shortages resulted, as did a fear of being near others who might carry the contagion. In households where one member of a family contracted the plague, other members of the family were quarantined, their doors marked with a red x to warn others of the presence of plague in the house. Usually other members of the family did contract and die from the disease although there were instances of individuals, particularly children, dying from starvation after their parents succumbed to plague.

Bodiam Castle.

Even beyond the outbreaks of plague, the Middle Ages were a dangerous, unhealthy time. Women frequently died in childbirth, infant and child mortality rates were high and life expectancies short, what would now be minor injuries frequently resulted in infection and death, and sanitary conditions and personal hygiene, particularly among the poor, were practically non-existent. Even the moats around castles that seem romantic in the 21st century were often little more than open sewers.

With these conditions, it’s not surprising that people of the Middle Ages lived with a persistent sense of mortality and, for many, a devout grasp on the Church’s promise of Heaven. Life on earth was viewed as a vale of tears, a hardship to endure until one reached the afterlife. In addition, some believed physical disabilities and ailments, including the plague, to be the judgment of God for sin.

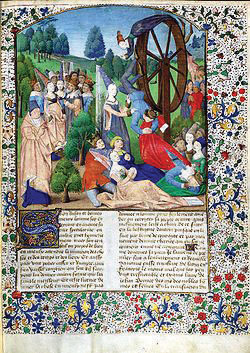

Fortuna spinning her Wheel of Fortune, from a work of Boccaccio.

An important image in the Middle Ages was the wheel of fortune. Picturing life as a wheel of chance, where an individual might be on top of the wheel (symbolic of having good fortune in life) one minute and on the bottom of the wheel the next, the image expressed the belief that life was precarious and unpredictable. In Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, the monk, for example, tells of individuals who enjoyed good fortune in life until a turn of the wheel brought them tragedy.

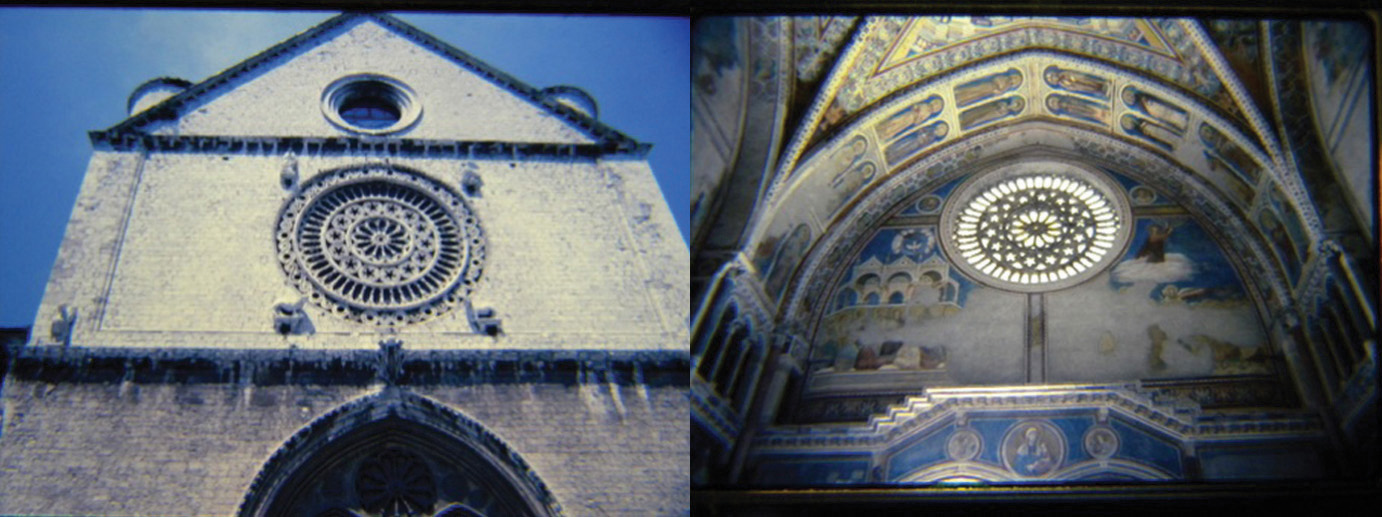

The Church incorporated the wheel of fortune in its imagery. Many medieval cathedrals feature rose windows. From the exterior of the church, the stone tracery of the window looks similar to a wheel of fortune; from within the church, sunlight floods through the glass, revealing its beauty. Symbolically, those outside the Church are at the mercy of fortune’s vagaries; those in the Church see the light through the stonework, suggesting the light of truth and faith, the light of Christ, available to those within the Church.

Rose window in the Basilica of St. Francis in Assissi, Italy.

Note how the stone tracery from the outside looks like a wheel of fortune. From inside the Church, the light is apparent.

Chivalry

In addition to religion, a second philosophical influence on medieval thought and literature was chivalrythe code of conduct which bound and defined a knight’s behavior, the code of conduct that bound and defined a knight’s behavior.

The ideals of chivalry form the basis of the familiar Arthurian legends, the stories of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. Historians generally agree that, if Arthur existed, it was most likely in the time period after the Roman legions left Britain undefended in the fifth century. Arthur was likely a Celtic/Roman leader who, for a time, repelled the invading Anglo-Saxons. However, the King Arthur of the familiar legends is a fictional figure of the later Middle Ages, along with his Queen Guinevere, the familiar knights such as Lancelot and Gawain, his sword Excalibur, Merlin the magician, and his kingdom of Camelot.

The concepts of chivalry and courtly love, unlike King Arthur, were real. The word chivalry, based on the French word chevalerie, derives from the French words for horse (cheval) and horsemen, indicating that chivalry applies only to knights, the nobility. Under the code of chivalry, the knight vowed not only to protect his vassals, as demanded by the feudal system, but also to be the champion of the Church.

Literature

Because the Church and the concept of chivalry were dominant factors in the philosophy of the Middle Ages, these two ideas also figure prominently in medieval literature.

Religious literature

Religious literature appeared in several genres:

-

devotional books

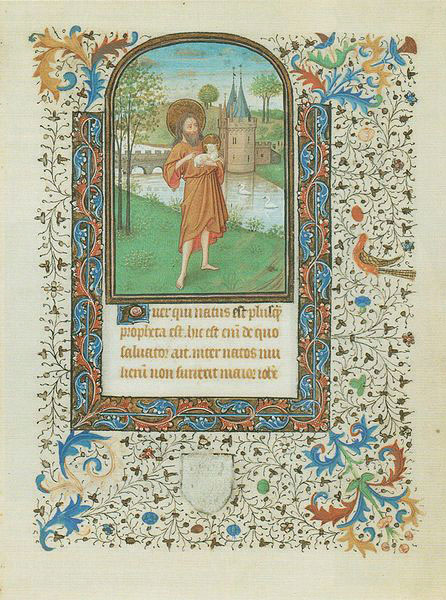

- books of hours [collections of prayers and devotionals, often illuminated]

- sermons

- psalters [books containing psalms and other devotional material, often illuminated]

- missals [books containing the prayers and other texts read during the celebration of mass throughout the year]

- breviaries [books containing prayers and instructions for celebrating mass]

- hagiographies [stories of the lives of saints]

-

medieval drama

- mystery playsa play depicting events from the Bible [plays depicting events from the Bible]

- morality playsa play depicting representative characters in moral dilemmas with both the good and the evil parts of their character struggling for dominance [plays, often allegories, intended to teach a moral lesson]

John the Baptist from a medieval book of hours.

Like the oral tradition of the Anglo-Saxon age, mystery plays and morality plays served a predominantly illiterate population.

Britain’s National Trust presents a video describing the Sarum Missal printed by Caxton, an important extant example of the religious literature of the Middle Ages, as well as a second brief video of their turn-the-pages digital copy of the missal that allows a closer inspection of several pages. The British Library features a turn-the-pages digital copy of the Sherborne Missal.

Chivalric literature

In Britain, chivalric literature, particularly the legends of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, flowered in the medieval romancea narrative, in either prose or poetry, presenting a knight and his adventures, a narrative, in either prose or poetry, presenting a knight and his adventures. The word romance originally indicated languages that derived from Latin (the Roman language) and is not related to modern usage of the word to signify romantic love. Instead a medieval romance presents a knight in a series of adventures (a quest) featuring battles, supernatural elements, repeated events, and standardized characters.

Caxton and the Printing Press

Caxton revolutionized the history of literature in the English language in 1476 when he set up the first printing press in England somewhere in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. The first to print books in English, Caxton helped to standardize English vocabulary and spelling.

The all-encompassing influence of the Church helped create a demand for devotional literature as literacy spread, particularly among the upper and middle classes. Although more people could read, they seldom could read Latin, the language in which clergy recorded most literature. To meet the demand for literature in the vernacular, Caxton printed works in English, including Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. The British Library provides digital images of both the first and second editions that Caxton printed.

Key Takeaways

- After the Norman conquest in 1066, the English language began its gradual transformation from Old English to Middle English.

- Feudalism and chivalry are evident in much Middle English literature.

- The Church was highly influential in daily life of the Middle Ages and in medieval literature.

- William Caxton helped standardize the language and satisfied a demand for literature in the vernacular when he introduced the printing press to England in 1476.

Resources: The Medieval World

Language

- The English Language in the Fourteenth Century. The Geoffrey Chaucer Page. Harvard University. Text, contemporaneous quotations, additional links. http://courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/language.htm

- “The Norman Conquest.” Learning: Changing Language. British Library. http://www.bl.uk/learning/langlit/changlang/activities/lang/norman/normaninvasion.html

Society

- “Feudal Life.” Annenberg Media Learner.org. Interactives. Text and additional topics. http://www.learner.org/interactives/middleages/feudal.html

- “Feudalism and Medieval Life.” Britain Express. English History. http://www.britainexpress.com/History/Feudalism_and_Medieval_life.htm

- “The Great Chain of Being.” 100 Years of Carnegie. Aristotle. Image and explanation. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/history/carnegie/aristotle/chainofbeing.html

- “Medieval Realms.” Alixe Bovey. Learning: Medieval Realms. British Library. Rural life slideshow, text, and images. http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/medieval/rural/rurallife.html

- “Towns.” Alixe Bovey. Learning: Medieval Realms. British Library. Slideshow, text, and images. http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/medieval/towns/medievaltowns.html

Philosophy

- “Black Death.” Mike Ibeji. British History In-Depth. BBC. Text, images, contemporaneous quotation. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/middle_ages/black_01.shtml#top

- “The Black Death: Art.” E.L. Skip Knox. History of Western Civilization. Boise State University. http://www.boisestate.edu/courses/westciv/plague/19.shtml

- “Chivalry.” The End of Europe's Middle Ages. Applied History Research Group. University of Calgary. http://www.ucalgary.ca/applied_history/tutor/endmiddle/FRAMES/feudframe.html

- “Church.”Alixe Bovey. Learning: Medieval Realms. British Library. Slideshow, text, and images. http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/medieval/thechurch/church.html

- “Death.” Alixe Bovey. Learning Medieval Realms. British Library. Text and images. http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/medieval/death/medievaldeath.html

- “King Arthur.” Alan Lupack and Barbara Tepa Lupack, Editors. The Camelot Project. University of Rochester. Texts, background, images, bibliographies. http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/arthmenu.htm

- “Medieval Tragedy.” Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Image, text, and additional links. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/SLT/drama/medievaltragedy.html

- “Religion.” Annenberg Media Learner.org. Interactives. Text and additional topics. http://www.learner.org/interactives/middleages/religion.html

- “The Spread of the Black Death.” Applied History Research Group. University of Calgary. Map and text. http://www.ucalgary.ca/applied_history/tutor/endmiddle/bluedot/blackdeath.html

- “Thomas Malory’s ‘Le Morte Darthur.’” Online Gallery. British Library. information on Malory, Malory’s manuscript, the Arthurian legend, and the historical Arthur. http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/englit/malory/index.html

Literature

- The Morality Plays. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Image, text, and additional links. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/SLT/drama/moralities.html

- The Mystery Cycles. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Image, text, and additional links. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/SLT/drama/mysteries.html

- “The Sarum Missal—Lyme Park, Cheshire.” Turning the Pages of History: The Lyme Caxton Missal. The National Trust. http://youtu.be/hDXki-iiiqM

- “The Sherborne Missal.” Virtual Books. Online Gallery. British Library. http://ttpdownload.bl.uk/app_files/silverlight/default.html?id=181afc99-df1f-4951-8981-df7e26625850

- “Turning the Pages: The Sarum Missal, Lyme Park, Cheshire. The National Trust. http://youtu.be/B0rZyH5U44w

Caxton and the Printing Press

- Caxton’s English. British Library. Treasures in Full. Text, images, additional links. http://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/english.html

- Caxton’s Chaucer. British Library. Treasures in Full. Text, images, additional links. http://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/caxtonslife.html

- Caxton’s Chaucer. British Library. Treasures in Full. Interactive digital images of the first and second editions of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. http://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/homepage.html

- William Caxton and the Printing Press. Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College. Video. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1lMn5OGJrPU

- William Caxton (c.1422–1492). Historic Figures. BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/caxton_william.shtml

- William Caxton and the Printing Press. Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College. Video. http://youtu.be/rQ1-9VsUY1o

- William Caxton (c.1422–1492). Historic Figures. BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/caxton_william.shtml

1.2 William Caxton and Printing in England

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objective

- Recognize the effects of William Caxton’s printing press on the development of the English language and British literature.

With the suppression of the Old English language at the time of the Norman Conquest and the replacement of English with French in official venues, English might have been lost forever. Instead, the English language survived and eventually flourished in the late Middle Ages. The future of the English language was further ensured with the arrival of William Caxton and the printing press in England. View a video mini-lecture on Caxton to learn about Caxton’s influence on the English language.

Caxton’s printing device.

The Printing Press

In 1476, Caxton set up a printing press in the vicinity of Westminster Abbey and began to print books, some in Latin as had been traditional, but Caxton also printed books in English. Because there was no standardization in English spelling, Caxton’s choices often became the standard.

Caxton showing the first specimen of his printing to King Edward IV at the Almonry, Westminster.

Daniel Maclise, 1851

The British Library has made available online a comparison of Caxton’s two printings of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, 1476 and 1483. In addition, Barbara Bordalejo in the Canterbury Tales Project at De Montfort University provides a digitized version of the British Library manuscripts that allows the reader to see the Middle English text side by side with the manuscript version and to search for specific lines and words. Britain’s National Archives contains the first document printed by Caxton.

KUHF radio station in Houston, Texas broadcasts “Engines of Our Ingenuity.” John H. Lienhard, Professor Emeritus of Mechanical Engineering and History at the University of Houston, wrote and narrates an audio of an episode on Caxton and the printing press. The website includes both the podcast and a written text.

Key Takeaway

- Caxton’s establishment of the printing press in England helped standardize the English language and promote the use of English in written texts.

Exercises

- The Folger Shakespeare Library provides a video demonstration of an early modern printing press. While watching the video, make a list of words used in early printing techniques that are still used, even with today’s computerized printing techniques.

- Caxton is credited with helping to promote the use of the English language. After reading the British Library’s section on Caxton’s Texts, including the section on Caxton’s English, write a brief paragraph explaining why Caxton chose to print works in the vernacular rather than in Latin.

Resources: William Caxton and Printing in England

Biography

- “Caxton’s Chaucer.” Treasures in Full. British Library. http://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/homepage.html

- “Caxton’s Life.” Treasures in Full: Caxton’s Chaucer. British Library. http://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/caxtonslife.html

- William Caxton (c.1422–1492). Historic Figures. BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/caxton_william.shtml

- “William Caxton.” History. Famous People and the Abbey. Westminster Abbey. http://www.westminster-abbey.org/our-history/people/william-caxton

Printing Press

- “Caxton’s English.” Treasures in Full: Caxton’s Chaucer. British Library. http://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/english.html

- “Caxton’s Technologies.” Treasures in Full: Caxton’s Chaucer. British Library. http://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/caxtonstechnologies.html

- “Caxton’s Texts.” Treasures in Full: Caxton’s Chaucer. British Library. http://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/caxtonstexts.html

- “The First Page Printed in England.” Treasures. National Archives. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/museum/item.asp?item_id=9

- “William Caxton.” John H. Leinhard. Engines of Our Ingenuity. University of Houston's College of Engineering. podcast and text. http://www.uh.edu/engines/epi785.htm

Caxton’s Chaucer

- Caxton's Canterbury Tales: The British Library Copies. Barbara Bordalejo. Canterbury Tales Project. De Montfort University. http://www.cts.dmu.ac.uk/Caxtons/

- “Caxton’s Chaucer.” Treasures in Full. British Library. http://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/homepage.html

Video

- “Printing 101.” Steven Galbraith, Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Books. Folger Shakespeare Library. http://youtu.be/lX6e8Q2nc5A

- William Caxton and the Printing Press. Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College. http://www.youtube.com/user/DrLoweMCC#p/u/18/1lMn5OGJrPU

1.3 Medieval Drama

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Define and explain the purpose of mystery plays and morality plays.

- Identify an example of a mystery play and of a morality play.

The long-held scholarly account of medieval drama asserts that the religious drama of the Middle Ages grew from the Church’s services, masses conducted in Latin before a crowd of peasants who undoubtedly did not understand what they were hearing. This idea certainly fits with the concept of church architecture in its cruciform shape to picture the cross, its stained glass windows to portray biblical stories, and other features designed to convey meaning to an illiterate population. Many scholars suggest that on special days in the liturgical year, the clergy would act out an event from the Bible, such as a nativity scene or a reenactment of the resurrection. Gradually, these productions became more complex and moved outside to the churchyard and then into the village commons.

Other scholars, however, suggest a different origin of medieval drama, claiming that it grew parallel to but outside of Church services which continued with their dramatic features as part of the mass.

Mystery Plays

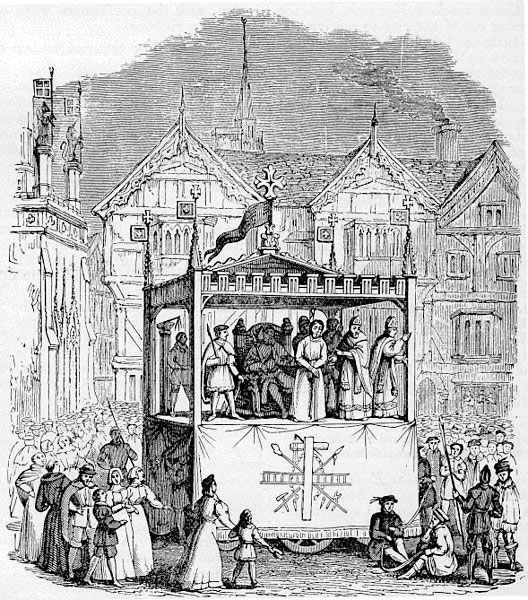

A pageant wagon in Chester, England.

From Book of Days by Robert Chamber

Mystery plays depict events from the Bible. Often mystery plays were performed as cycle playsa sequence of plays portraying all the major events of the Bible, from the fall of Satan to the last judgment, a sequence of plays portraying all the major events of the Bible, from the fall of Satan to the last judgment. Some play cycles were performed by guilds, each guild taking one event to dramatize. One of the most famous of the play cycles, the York mystery plays, is still performed in the English city of York. Records from the Chester cycle, also still performed, list which guilds were involved and which plays each guild presented. In a few places, such as York, the cycles were performed on pageant wagons that moved on a pre-determined route through the city. By staying in the same place, the audience could see each individual play as the wagon stopped and the actors performed before moving on to perform again at the next station. Four English cities were particularly noted for their cycles of mystery plays: Chester, York, Coventry, and Towneley (referred to as the Wakefield plays). Dennis G. Jerz, Associate Professor of English at Seton Hall University, created a simulation of the path of the pageant wagons through York, showing the route and the order of the plays.

The Second Shepherds’ Play

One of the most well-known of the mystery plays is The Second Shepherds’ Play, part of the Wakefield cycle. The play blends comic action, serious social commentary, and the religious story of the angelic announcement of Christ’s birth to shepherds. At the beginning of the play, three shepherds complain of the injustices of their lives on the lowest rung of the medieval social ladder. When another peasant steals one of their lambs, the thief and his wife try to hide the animal by disguising it as their infant son; thus, an identification of a new-born son with the symbolic lamb foreshadows the biblical story. At the end of the play, the religious message becomes clear when angels announce the birth of Christ.

The text of The Second Shepherds’ Play is available on the following sites:

- Bibliotheca Anglica Middle English Literature. Bibliotheca Augustana. University of Augsburg. http://www.hs-augsburg.de/~harsch/anglica/Chronology/15thC/WakefieldMaster/wak_shep.html

- Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=cme;idno=Towneley;rgn=div1;view=text;cc=cme;node=Towneley%3A13

- “The Second Shepherds’ Play.” The Electric Scriptorium. University of Calgary, Canada. http://people.ucalgary.ca/~scriptor/towneley/plays/second.html

- “The Second Shepherds’ Play.” Ernest Rhys, ed. Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/19481/19481-h/19481-h.htm

Morality Plays

Morality plays are intended to teach a moral lesson. These plays often employ allegorythe use of characters or events in a literary work to represent abstract ideas or concepts, the use of characters or events in a literary work to represent abstract ideas or concepts. Morality plays, particularly those that are allegorical, depict representative characters in moral dilemmas with both the good and the evil parts of their character struggling for dominance. Similar to mystery plays, morality plays did not act out events from the Bible but instead portrayed characters much like the members of the audience who watched the play. From the characters’ difficulties, the audience could learn the moral lessons the Church wished to instill in its followers.

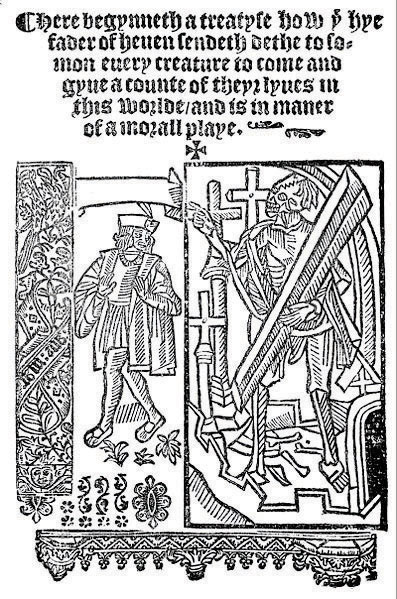

First page of medieval print version of Everyman.

One of the most well known of extant morality plays is Everyman. In this morality play, God sends Death to tell Everyman that his time on earth has come to an end.

The text of Everyman is available on the following sites:

- Everyman. Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=cme;cc=cme;view=toc;idno=Everyman

- Everyman. Ernest Rhys, ed. Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/19481/19481-h/19481-h.htm

- Everyman. Renascence Editions. University of Oregon. http://www.luminarium.org/renascence-editions/everyman.html

- Everyman. W. Carew Hazlitt, ed. Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/9050/pg9050.html

Key Takeaways

- Medieval drama provided a method for the Church to teach a largely illiterate population.

- Two primary forms of medieval drama were the mystery play and the morality play.

Resources: Medieval Drama

History of Medieval Drama

- “The Dawn of the English Drama.” Theater Database. rpt. from Truman. J. Backus. The Outlines of Literature: English and American. New York: Sheldon and Company, 1897. 80–84. http://www.theatredatabase.com/medieval/dawn_of_the_english_drama.html

- “Drama of the Middle Ages.” Theater Database. http://www.theatredatabase.com/medieval/medieval_theatre_001.html

- “The Medieval Drama.” Theater Database. rpt. from Robert Huntington Fletcher. A History of English Literature for Students. Boston: Richard G. Badger, 1916. 82–91. http://www.theatredatabase.com/medieval/medieval_drama_001.html

- “The Medieval Drama.” TheatreHistory.com. rpt. from Brander Matthews. The Development of the Drama. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1912. 107–146. http://www.theatrehistory.com/medieval/medieval001.html

- “Medieval Drama: Myths of Evolution, Pageant Wagons, and (lack of) Entertainment Value.” Carolyn Coulson-Grigsby. The ORB: Online Reference Book for Medieval Studies. http://www.the-orb.net/non_spec/missteps/ch5.html

- “Medieval Drama: An Introduction of Middle English Plays.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt. from Robert Huntington Fletcher. A History of English Literature. Boston: Richard G. Badger, 1916. 85–91. http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/medievaldrama.htm

- “Middle English Plays.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. Links to an introduction of medieval drama in England, texts of plays, and scholarly information on medieval drama. http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/plays.htm

Mystery Plays

- “The Chester Guilds.” Chester Mystery Plays. History including a pop-up list of guilds responsible for specific plays in the Chester cycle. http://www.chestermysteryplays.com/history/history/morehistory.html

- “The Collective Story of the English Cycles.” Theatre Database.com. rpt. from Charles Mills Gayley. Plays of Our Forefathers. New York: Duffield & Co., 1907. 118–24. http://www.theatredatabase.com/medieval/collective_story_of_the_english_cycles.html

- “Medieval Church Plays.” TheatreHistory.com. rpt. from Alfred Bates, ed. The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization, Vol. 7. London: Historical Publishing Company, 1906. 2–3, 6–10. http://www.theatrehistory.com/medieval/mysteries001.html

- “Mysteries and Pageants in England.” TheatreHistory.com. rpt. from Martha Fletcher Bellinger. A Short History of the Drama. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1927. 132–7. http://www.theatrehistory.com/medieval/mysteries002.html

- “Popular English Drama: The Mystery Plays.” L.D. Benson. The Geoffrey Chaucer Page. Harvard University. http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/special/litsubs/drama/

- Simulation of York Corpus Christi Play. Dennis G. Jerz. An interactive map that illustrates the progression of the plays through the city of York. http://jerz.setonhill.edu/resources/PSim/applet/index.html

- “What Are the York Mystery Plays?” York Mystery Plays. A brief history of the York plays and information about current productions. http://www.yorkmysteryplays.org/default.asp?idno=4

- “What’s the Mystery?: Medieval Miracle Plays.” Folger Shakespeare Library. http://www.folger.edu/template.cfm?cid=2514

- “The York Plays.” Chester N. Scoville and Kimberley M. Yates. Records of Early English Drama (REED): Centre for Research in Early English Drama. University of Toronto. http://www.reed.utoronto.ca/yorkplays/york.html#pag

Text of The Second Shepherds’ Play

- Bibliotheca Anglica Middle English Literature. Bibliotheca Augustana. University of Augsburg. http://www.hs-augsburg.de/~harsch/anglica/Chronology/15thC/WakefieldMaster/wak_shep.html

- Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=cme;idno=Towneley;rgn=div1;view=text;cc=cme;node=Towneley%3A13

- “The Second Shepherds’ Play.” The Electric Scriptorium. University of Calgary, Canada. http://people.ucalgary.ca/~scriptor/towneley/plays/second.html

- “The Second Shepherds’ Play.” Ernest Rhys, ed. Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/19481/19481-h/19481-h.htm

Morality Plays

- “Allegory.” The University of Victoria’s Hypertext Writer’s Guide. Department of English. University of Victoria. http://web.uvic.ca/wguide/Pages/LTAllegory.html

- Everyman. Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. Links to an introduction to Everyman, sites including the text of the play, and scholarly information about the play. http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/everyman.htm

- “Moralities, Interludes and Farces of the Middle Ages.” Moonstruck Drama Bookstore. rpt. from Martha Fletcher Bellinger. A Short History of the Drama. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1927. 138–44. http://www.imagi-nation.com/moonstruck/spectop006.html

- “The Morality Plays.” Drama. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/SLT/drama/moralities.html

Text of Everyman

- Everyman. Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=cme;cc=cme;view=toc;idno=Everyman

- Everyman. Ernest Rhys, ed. Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/19481/19481-h/19481-h.htm

- Everyman. Renascence Editions. University of Oregon. http://www.luminarium.org/renascence-editions/everyman.html

- Everyman. W. Carew Hazlitt, ed. Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/9050/pg9050.html

Video

- A Brief Introduction to the York Mystery Plays 2010. Information about the modern production of the York cycle. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8nyFLOlEupM

- “From an Ill-Spun Wool: The Second Shepherds' Play and Early English Theater.” Folger Shakespeare Library. Podcast lectures about the staging of the play and the origin of the play. http://www.folger.edu/template.cfm?cid=2615

- The History of the Theatre: Medieval Theatre. Richard Parker. Theatre Arts Instructor, Columbia Gorge Community College. Lecture on early drama from an online theater history class at Columbia Gorge Community College. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QxdDoUoFQhM

- “Noah’s Deluge, Part 2.” Chester Mystery Plays. A video of one of the 2009 Chester plays. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PxQ6sihBKmU&p=1D92A5E5AEF6B6A5&playnext=1&index=3

1.4 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify literary techniques used in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

- Identify and account for the pagan and Christian elements in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

- Define medieval romance and apply the definition of the genre to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

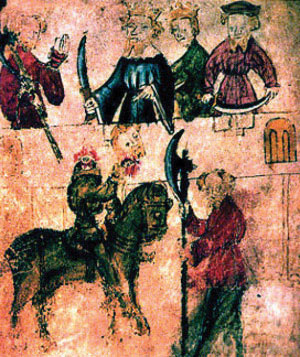

Beheading of the Green Knight.

From the manuscript Cotton Nero A.x, f. 94b

The last 40 years of the Middle Ages, from 1360 to 1400, produced the three greatest works of medieval literature:

- Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales

- Malory’s Morte d’Arthur

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight by the Pearl Poetthe unidentified author of Pearl, Patience, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the unidentified author of Pearl, Patience, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

Scholars believe the same unknown individual wrote Pearl, Patience, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, thus referring to him as the Pearl poet.

Text

Modern English Text

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Jessie L. Weston. In Parentheses. Middle English Series. York University. Verse translation. http://www.yorku.ca/inpar/

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Jessie L. Weston. University of Rochester. The Camelot Project. Prose translation. http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/sggk.htm

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Paul Deane. Forgotten Ground Regained: A Treasury of Alliterative and Accentual Poetry. Verse translation. http://alliteration.net/Pearl.htm

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. University of Toronto Libraries. Middle English with prose translation. http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poem/62.html

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. W. A. Neilson. In Parentheses. Middle English Series. York University. Prose translation. http://www.yorku.ca/inpar/sggk_neilson.pdf

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A Close Verse Translation. Geoffrey Chaucer Page. Harvard University. http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/ready.htm

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A Middle English Arthurian Romance Retold in Modern Prose. Jessie L. Weston. Google Books. http://books.google.com/books?id=j8l7-HnlMfkC&printsec=frontcover&dq=sir+gawain+and+the+green+knight&source=bl&ots=C7I7E8GMVE&sig=cvMDxdXVp1PqOueBlJSEZPjXhpE&hl=en&ei=x2twTMmFKoL7lweM6smADg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=13&ved=0CFsQ6AEwDA#v=onepage&

Original Text

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The Cotton Nero A.x. Project. Dr.Murray McGillivray, University of Calgary, Team Leader. University of Calgary. http://people.ucalgary.ca/~scriptor/cotton/transnew.html

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. University of Toronto Libraries. Middle English with prose translation. http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poem/62.html

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. J.R.R. Tolkien and E.V. Gordon. Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=cme;cc=cme;rgn=main;view=text;idno=Gawain

Audio

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. W. H. Neilson. LibriVox. Recording in modern English. http://www.archive.org/details/gawain_mj_librivox

Alliterative Revival

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is part of a movement known as the alliterative revivala resurgent use of the alliterative verse form of oral Old English poetry such as Beowulf, a resurgent use of the alliterative verse form of oral Old English poetry such as Beowulf. In the following lines, the first two lines of the poem, note the repetition of the s sounds in line 1 and in line 2 the b sounds:

Sidebar 2.1.

Siþen þe sege and þe assaut watz sesed at Troye,

þe borʒ brittened and brent to brondeʒ and askez

Sidebar 2.2.

Since the siege and the assault was ceased at Troy,

The burg [city] broken and burned to brands [cinders] and ashes

Bob and Wheel

As these first two lines of the poem illustrate, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is written in long alliterative lines, each stanza having a varying number of lines. These long alliterative lines are followed by the bob and wheela group of five short lines at the end of an alliterative verse rhyming ABABA, a group of five short lines at the end of an alliterative verse rhyming ABABA.

For example, in stanza three, beginning with line 37, the story begins with a description of King Arthur and his court at Camelot in eighteen long alliterative lines followed by the five short lines of the bob and wheel:

Sidebar 2.3.

on sille

þe hapnest under heuen

kyng hyʒest mon of wylle

hit werere now gret nye to neuen

so hardy ahere on hille

Sidebar 2.4.

in the hall

the most fortunate ones under heaven

highest king of most will

it is now hard to name

so hardy a one on the hill

Notice the two-syllable line called the bob and the four lines called the wheel:

Sidebar 2.5.

on sille

þe hapnest under heuen

kyng hyʒest mon of wylle

hit werere now gret nye to neuen

so hardy ahere on hille

Also notice the ABABA rhyme scheme:

Sidebar 2.6.

| on sille | A |

| þe hapnest under heuen | B |

| kyng hyʒest mon of wylle | A |

| hit werere now gret nye to neuen | B |

| so hardy ahere on hille | A |

Green Man Myth

Also like Old English poetry, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, although composed well into the Middle Ages when the Church dominated society, combines hints of paganism in the figure of the Green Knight with obvious Christian elements in Sir Gawain. The Green Knight is a type of Green Mana character in ancient fertility myths representing spring and the renewal of life, a character in ancient fertility myths representing spring and the renewal of life, a parallel of Christian belief in resurrection. In some decapitation myths, a motif found in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the blood of the Green Man symbolizes the fertilizing of crops, thus insuring an adequate food supply. Surprisingly, Green Man symbols are common in Gothic cathedrals, such as these in Ely Cathedral, in York Minster, and in the ruins of Fountains Abbey.

Green Man in Ely Cathedral.

Green Man in York Minster.

Green Man in the ruins of Fountains Abbey.

Chivalry and Courtly Love

In this story, the actions of Sir Gawain and the rest of King Arthur’s knights are measured by chivalry, the code of conduct which bound and defined a knight’s behavior. In fact, the ordeal that Sir Gawain endures is eventually revealed to be a test of the Court’s dedication to their vows of knighthood.

The concept of medieval chivalry was famously described in 1891 by Leon Gautier, who listed ten rules of chivalry from the 11th and 12th centuries:

- Thou shalt believe all that the Church teaches and shalt observe all its directions.

- Thou shalt defend the Church.

- Thou shalt respect all weaknesses and shalt constitute thyself the defender of them.

- Thou shalt love the country in the which thou wast born.

- Thou shalt not recoil before thine enemy.

- Thou shalt make war against the infidel without cessation, and without mercy.

- Thou shalt perform scrupulously thy feudal duties, if they be not contrary to the laws of God.

- Thou shalt never lie, and shalt remain faithful to thy pledged word.

- Thou shalt be generous, and give largesse to everyone.

- Thou shalt be everywhere and always the champion of the Right and the Good against Injustice and Evil.

In addition to the ideals of chivalry, the nobility often modeled their behavior, in literature at least, on the concept of courtly loverules governing the behavior of knights and ladies in a ritualistic, formalized system of flirtation, rules governing the behavior of knights and ladies in a ritualistic, formalized system of flirtation. Courtly love is an integral part of the medieval romances sung by troubadours as entertainment in the courts of France, stories of knights inspired to great deeds by their love for fair damsels, sometimes a damsel in distress rescued by the knight. The idea behind amour courtois is that a knight idealized a lady, a lady not his wife and often in fact married to another, and performed deeds of chivalry to honor her.

“Rules” governing the conduct of a knight involved in courtly love were outlined by Andreas Capellanus in his 12th-century book The Art of Courtly Love. The ORB: Online Reference Book for Medieval Studies lists Capellanus’ rules:

- Marriage is no real excuse for not loving.

- He who is not jealous cannot love.

- No one can be bound by a double love.

- It is well known that love is always increasing or decreasing.

- That which a lover takes against his will of his beloved has no relish.

- Boys do not love until they arrive at the age of maturity.

- When one lover dies, a widowhood of two years is required of the survivor.

- No one should be deprived of love without the very best of reasons.

- No one can love unless he is impelled by the persuasion of love.

- Love is always a stranger in the home of avarice.

- It is not proper to love any woman whom one should be ashamed to seek to marry.

- A true lover does not desire to embrace in love anyone except his beloved.

- When made public love rarely endures.

- The easy attainment of love makes it of little value; difficulty of attainment makes it prized.

- Every lover regularly turns pale in the presence of his beloved.

- When a lover suddenly catches sight of his beloved his heart palpitates.

- A new love puts to flight an old one.

- Good character alone makes any man worthy of love.

- If love diminishes, it quickly fails and rarely revives.

- A man in love is always apprehensive.

- Real jealousy always increases the feeling of love.

- Jealousy, and therefore love, are increased when one suspects his beloved.

- He whom the thought of love vexes, eats and sleeps very little.

- Every act of a lover ends with the thought of his beloved.

- A true lover considers nothing good except what he thinks will please his beloved.

- Love can deny nothing to love.

- A lover can never have enough of the solaces of his beloved.

- A slight presumption causes a lover to suspect his beloved.

- A man who is vexed by too much passion usually does not love.

- A true lover is constantly and without intermission possessed by the thought of his beloved.

- Nothing forbids one woman being loved by two men or one man by two women.

Note that many of the stereotypical signs of being in love are listed, such as appearing pale (#15), being unable to eat or sleep (#23), and displaying jealousy (#21). Other familiar concepts such as playing hard to get (#14) and secret loves (#13) come from the rules of courtly love. The rules also make clear that engaging in the rituals of courtly love is only for the nobility (#11).

The concept of courtly love and the medieval romance arrived in Britain with Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine, a region in what is now France, and her marriage to the English King Henry II.

Images from the Middle Ages portray noble couples in typical aristocratic medieval activities: playing chess, hunting with falcons, dancing, and, in some images, obviously engaging in courtly flirtations. In one scene, for example, a lady appears to be presenting a token to a knight. In another, a knight appears to have stabbed himself, possibly in despair over his unrequited love. In another scene, knights fight in a tournament while adoring ladies watch from the stands.

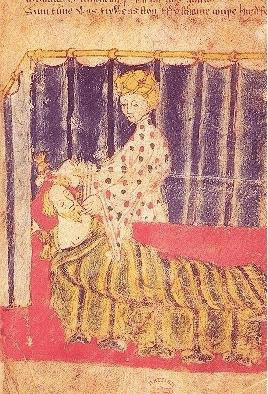

Temptation of Sir Gawain by Lady Bertilak.

From the manuscript Cotton Nero A. x, f. 129

Medieval Romance

In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, both the code of chivalry and the rituals of courtly love govern Sir Gawain’s behavior and decisions, as would be expected in a medieval romance, a narrative with the following characteristics:

- a plot about knights and their adventures

- improbable, often supernatural, elements

- conventions of courtly love

- standardized characters (the same types of characters appearing in many stories: the chivalrous knight; the beautiful lady; the mysterious old hag)

- repeated events, often repeated in numbers with religious significance such as three

Key Takeaways

- One of the major writers of the Middle Ages is the unidentified Pearl Poet, and one of his major works is Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight exhibits literary techniques typical of the alliterative revival.

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight reveals vestiges of paganism in a society dominated by Christianity.

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight illustrates two concepts important to medieval nobility: chivalry and courtly love.

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight exemplifies the medieval romance genre.

Exercises

- Review the rules of chivalry as reported by Leon Gautier. On which points does Sir Gawain fail to live up to his vows of knighthood?

- How do the tenets of courtly love affect Sir Gawain’s interaction with Lady Bertilak?

- Do you detect any incongruities in the two systems of chivalry and courtly love?

- Describe the two “games” in which Sir Gawain becomes involved. What was the purpose of these two challenges?

- Identify examples of the characteristics of medieval romance apparent in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

Resources: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

General Resources

- “Music, Literature and Illuminated Manuscripts.” Learning: Medieval Realms. British Library. http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/medieval/musicartlit/musicartliterature.html

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. Links to text, images, and scholarly information. http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/gawainre.htm

Modern English Text

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Jessie L. Weston. In Parentheses. Middle English Series. York University. Verse translation. http://www.yorku.ca/inpar/

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Jessie L. Weston. University of Rochester. The Camelot Project. Prose translation. http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/sggk.htm

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Paul Deane. Forgotten Ground Regained: A Treasury of Alliterative and Accentual Poetry. Verse translation. http://alliteration.net/Pearl.htm

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. University of Toronto Libraries. Middle English with prose translation. http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poem/62.html

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. W. A. Neilson. In Parentheses. Middle English Series. York University. Prose translation. http://www.yorku.ca/inpar/sggk_neilson.pdf

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A Close Verse Translation. Geoffrey Chaucer Page. Harvard University. http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/ready.htm

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A Middle English Arthurian Romance Retold in Modern Prose. Jessie L. Weston. Google Books. http://books.google.com/books?id=j8l7-HnlMfkC&printsec=frontcover&dq=sir+gawain+and+the+green+knight&source=bl&ots=C7I7E8GMVE&sig=cvMDxdXVp1PqOueBlJSEZPjXhpE&hl=en&ei=x2twTMmFKoL7lweM6smADg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=13&ved=0CFsQ6AEwDA#v=onepage&

Original Text

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The Cotton Nero A.x. Project. Dr.Murray McGillivray, University of Calgary, Team Leader. University of Calgary. http://people.ucalgary.ca/~scriptor/cotton/transnew.html

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. J.R.R. Tolkien and E.V. Gordon. Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=cme;cc=cme;rgn=main;view=text;idno=Gawain

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. University of Toronto Libraries. Middle English with prose translation. http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poem/62.html

Audio

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. W. H. Neilson. LibriVox. Recording in modern English. http://www.archive.org/details/gawain_mj_librivox

The Pearl Poet

- “The Pearl Poet.” Paul Deane. Forgotten Ground Regained: A Treasury of Alliterative and Accentual Poetry. http://alliteration.net/Pearlman.html

- “The Pearl- (Gawain-) Poet.” Online Companion to Middle English Literature. Chair of Medieval English Literature and Historical Linguistics of the Heinrich-Heine-University Duesseldorf. http://user.phil-fak.uni-duesseldorf.de/~holteir/companion/Navigation/Authors/Pearl-Poet/pearl-poet.html

Courtly Love

- Andreas Capellanus. The Geoffrey Chaucer Page. Harvard University. http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/special/authors/andreas/index.html

- Andreas Capellanus: The Art of Courtly Love, (btw. 1174–1186). Paul Halsall. Internet Medieval Sourcebook. The ORB: Online Reference Book for Medieval Studies. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/capellanus.asp

- “Chivalry and Courtly Love.” David L. Simpson. DePaul University. http://condor.depaul.edu/dsimpson/tlove/courtlylove.html

- “’Courtly Love’ Images.” Dr. Debora B. Schwartz. English Department, College of Liberal Arts. California Polytechnic State University. http://cla.calpoly.edu/~dschwart/engl513/courtly/images.htm

1.5 Geoffrey Chaucer (1343–1400)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Explain the literary techniques Chaucer uses that distinguish Canterbury Tales from collections of unrelated stories.

- List and define types of tales used in Canterbury Tales.

- Categorize individual tales.

- Identify the social strata to which each pilgrim belongs and correlate the description of each character with the tale he/she tells.

“He [Chaucer] must have been a man of a most wonderful comprehensive nature, because, as has been truly observed of him, he has taken into the compass of his Canterbury Tales the various manners and humours (as we now call them) of the whole English nation in his age … 'tis sufficient to say, according to the old proverb, that here is God's plenty.”

John Dryden

With this quotation, John Dryden, 17th-century poet, essayist, and literary critic, encapsulates what many consider to be one of the prominent features of Chaucer’s work: The Canterbury Tales pictures the medieval world with a richness of description that makes it vibrant and alive. "The General Prologue" introduces individuals from every level of society—peasant, nobleman, clergy, and the new middle class—with vividness and detail.

Chaucer’s Pilgrims by late 18th-century poet and artist William Blake.

Biography

Anonymous portrait of Chaucer.

Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343–1400) was born into an apparently prosperous merchant family. As a boy he served as a page to a noble family and throughout his life worked in increasingly more prominent government positions. Chaucer’s wife Phillipa was the sister of John of Gaunt’s third wife Katherine, who had been a governess to the children of John and his wife Blanche. John of Gaunt, a wealthy and politically powerful younger son of King Edward III, became Chaucer’s patron. Whether through this family connection or on his own merit, Chaucer maintained a comfortable life through his position in the court. Chaucer’s poem The Book of the Duchess was written to commemorate the death of John of Gaunt’s wife Blanche.

When Chaucer died in 1400, he was buried in Westminster Abbey, an indication of his high social status. His tomb in the south transept of Westminster Abbey began the tradition of Poet’s Corner.

Chaucer’s tomb in Westminster Abbey.

Westminster Abbey.

Text

Text in Modern English Translation

- The Canterbury Tales. Michael Murphy. Brooklyn College, City University of New York. “The General Prologue” and selected tales in Middle English with “reader-friendly” prose translations. http://academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu/webcore/murphy/canterbury/canterbury.htm

- “The Canterbury Tales and Other Works.” Librarius. side-by-side translations. http://www.librarius.com/

- “Canterbury Tales: Prologue [Parallel Texts].” Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Paul Halsall. Fordham University. parallel edition of “The General Prologue.” http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/CT-prolog-para.html

- “ELF Presents The Canterbury Tales.” The Electronic Literature Foundation. http://www.canterburytales.org/canterbury_tales.html

- “Interlinear Translations of Some of The Canterbury Tales.” Geoffrey Chaucer Page. L.D. Benson. Harvard University. interlinear translations. http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/teachslf/tr-index.htm

Text in Middle English

- “Chaucer Texts.” eChaucer: Chaucer in the Twenty-First Century. Gerard NeCastro. University of Maine at Machias. Middle English text and prose translations. http://www.umm.maine.edu/faculty/necastro/chaucer/texts/

- The Canterbury Tales, and Other Poems. Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/catalog/world/readfile?fk_files=1448814&pageno=26

- Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=cme;idno=CT

- “Selected Poetry of Geoffrey Chaucer.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English. University of Toronto. http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poet/61.html

Audio

- “The Canterbury Tales.” Ed. D. Laing Purves (1838–1873). Librivox. complete audio files. http://librivox.org/the-canterbury-tales-by-geoffrey-chaucer/

- “The Canterbury Tales Audio Links.” Librarius. selected audio files. http://www.librarius.com/cantlink/audiofs.htm

- “Chaucer Canterbury Tales.” Luminarium. Anniina Jokinen. selected audio files. http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/canterbury.htm

- The Chaucer Metapage Audio Files. Virginia Military Institute. Audio files of “The General Prologue,” “The Knight’s Tale,” “The Miller’s Tale,” “The Wife of Bath’s Tale,” “The Envoy to the Clerk’s Tale,” “The Pardoner’s Tale,” and “The Nun’s Priest Tale.” http://www.vmi.edu/fswebs.aspx?tid=34099&id=34249

Types of Tales

Chaucer uses several types of tales typical in the Middle Ages.

-

medieval romance—a narrative with the following characteristics:

- a plot about knights and their adventures

- improbable, often supernatural elements

- inclusion of the conventions of courtly love

- standardized characters (the same types of characters appearing in many stories: the chivalrous knight; the beautiful lady; the mysterious old hag)

-

repeated events, often repeated in numbers with religious significance such as three

- examples of medieval romances in The Canterbury Tales: “The Knight’s Tale,” “The Wife of Bath’s Tale” (an Arthurian romance)

-

fabliaua humorous, bawdy tale, often including satire of foolish characters—a humorous, bawdy tale, often including satire of foolish characters

- examples of fabliaux in The Canterbury Tales: “The Miller’s Tale,” “The Reeve’s Tale,” “The Summoner’s Tale”

-

exempluma moral tale, often used to illustrate a point in a sermon—a moral tale, often used to illustrate a point in a sermon

- examples of exempla in The Canterbury Tales: “The Clerk’s Tale,” “The Pardoner’s Tale,” “The Monk’s Tale”

-

saint’s legenda story depicting the life and martyr’s death of a saint—a story depicting the life and martyr’s death of a saint

- examples of saints’ legends in The Canterbury Tales: “The Prioress’s Tale,” “The Second Nun’s Tale”

-

beast epica fable, often allegorical, that features animal characters—a fable, often allegorical, that features animal characters

- example of a beast epic in The Canterbury Tales: “The Nun’s Priest’s Tale”

Many of the tales Chaucer uses in The Canterbury Tales are not his original stories. Many come from other sources or are traditional stories. Chaucer’s originality is in his artful use of the material to create a unified work that portrays a vast array of medieval characters.

“The General Prologue”

Although collections of stories were not uncommon in the Middle Ages, Chaucer's Canterbury Tales are unique because they are more than a collection of unrelated tales; Chaucer produces a unified work through two techniques. First, he uses a frameworka narrative that contains another narrative: in Canterbury Tales, the fiction of the pilgrims on a pilgrimage that provides the structure and the rationale for the various tales, a narrative that contains another narrative: in Canterbury Tales, the fiction of the pilgrims on a pilgrimage that provides the structure and the rationale for the various tales. Thus the various stories form a whole fiction. Second, Chaucer provides linksconversations among the various pilgrims between the stories to tie the stories together, conversations among the various pilgrims between the stories to tie the stories together.

The first component of the framework is “The General Prologue” which introduces characters who tell the stories and who continue to function as characters in the links between the tales. In the first few lines Chaucer sets the stage, explaining the setting and the situation:

Sidebar 2.7.

Whan that Aprille, with hise shoures soote,

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

And bathed euery veyne in swich licour,

Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

Whan Zephirus eek with his swete breeth

Inspired hath in euery holt and heath

The tendre croppes and the yonge sonne

Hath in the Ram his halfe cours yronne,

And smale foweles maken melodye,

That slepen al the nyght with open eye,

So priketh hem nature in hir corages;

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

And Palmeres for to seken straunge strondes,

To ferne halwes kowthe in sondry londes

And specially, from euery shires ende

Of Engelond, to Caunturbury they wende,

The hooly blisful martir for to seke,

That hem hath holpen, whan þat they were secke.

from Frederick J. Furnivall’s edition of the Ellesmere Manuscript, 1868

These lines tell us that the pilgrims are on their way to Canterbury Cathedral. The following presentation provides pictures of and information about Canterbury Cathedral.

PowerPoint 2.1.

Follow-along file: PowerPoint title and URL to come.

Canterbury Cathedral.

Video Clip 2

Thomas Becket and the reason Chaucer’s pilgrims are traveling to Canterbury Cathedral.

(click to see video)The following study guide to “The General Prologue” will help identify key features of each of the pilgrims Chaucer introduces in the prologue.

PowerPoint 2.2.

Follow-along file: PowerPoint title and URL to come.

Eastbridge “Hospital" (a place of hospitality) in Canterbury where pilgrims to Canterbury Cathedral found food and shelter, built in the late 12th century.

Selected Individual Tales

“The Miller’s Tale”

An interlinear translation by Larry D. Benson is available on the Harvard Geoffrey Chaucer website.

“The Miller’s Tale” is an example of a fabliau. Fabliaux often involve students from the two great British medieval universities, Oxford and Cambridge, such as Nicholas, the Oxford student in “The Miller’s Tale.” (Only males attended medieval universities.) Many fabliaux probably were composed by students. Modern students may be surprised to learn that people of the Middle Ages thought college students might be involved in pursuing women, drinking, and playing pranks, or in making up stories that involved these activities. Or maybe modern college students would think that students haven’t changed much throughout the ages!

In “The Miller’s Tale” Chaucer brings together two plots from traditional stories:

- a student creates an opportunity to sleep with a woman by convincing her husband that Noah’s flood is about to be repeated

- a lover who is tricked into a humiliating misdirected kiss takes vengeance on his tormentor

These are traditional plots; Chaucer may or may not have been the first to write them. However, their union, culminating in Nicholas’s cry “Water,” is brilliantly handled by Chaucer.

“The Wife of Bath’s Tale”

The text of “The Wife of Bath’s Tale” is available on the Litrix Reading Room website.

“The Wife of Bath’s Tale” is a medieval romance, specifically an Arthurian romance. Not a major character in the tale, King Arthur appears in the story to pass judgment on the guilty knight, only to have his Queen Guinevere ask him to change his ruling. Thus, King Arthur’s giving in to the Queen’s desire is the first intimation of the lesson the errant knight must learn.

The Wife of Bath’s character and her tale have been seen as a reaction to the anti-feminism cultivated by the medieval church. Note the characters who interrupt her prologue and tale. Also often referred to as “the first feminist,” the Wife of Bath, as an actual medieval woman, would have had no concept of modern feminist viewpoints.

“The Clerk’s Tale”

An interlinear translation by Larry D. Benson is available on the Harvard Geoffrey Chaucer website.

Chaucer’s Clerk is also an Oxford student, but one much different from the gallant rascal Nicholas in the Miller’s story. A charity student, the Clerk has taken lower orders in the Church and studies philosophy. Serious about his studies, the Clerk has neither time for pranks nor money for drink; Chaucer in “The General Prologue” tells us that he spends his money on books. Another significant description of the Clerk is Chaucer’s assertion: “Gladly would he learn and gladly teach.”

“The Clerk’s Tale” with its apparent admonition about wives being submissive to their husbands is often contrasted with “The Wife of Bath’s Tale.” However, the fifth and sixth stanzas from the end of the tale reveal the Clerk’s real point in telling this story. Even the Clerk himself says that it would be unthinkable for wives to react as Griselda did, and he then establishes his story as an exemplum by explaining its religious lesson.

Key Takeaways

- Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales provides a vivid description of life in the Middle Ages by picturing in detail characters from every level of medieval society.

- Chaucer moves beyond the traditional collection of unrelated tales by making Canterbury Tales a unified whole through the use of literary techniques such as the framework of the pilgrimage, links, and the matching of a tale’s content to the personality of the pilgrim who tells it.

- Various types of tales such as medieval romance, fabliau, exemplum, saint’s legend, and beast epic make up Canterbury Tales.

Exercises

- Although collections of stories were not uncommon in the Middle Ages, Chaucer's Canterbury Tales are unique because they are more than a collection of unrelated tales; Chaucer produces a unified work through two techniques. First, he uses the framework of the pilgrimage to make the various stories part of a whole fiction. Part of that framework consists of conversations among the various characters between the stories to help tie the stories together. These bits of conversation which tie the stories together are called links. Locate examples of links. Explain the content of each link and evaluate the effectiveness of the link in relating the characters and the stories to each other.

- Another technique Chaucer used to make Canterbury Tales a unified work is the careful choosing of a story that is appropriate for the character who tells it. Chaucer introduces each character in the "General Prologue," and then he frequently adds information in the links or in the character's prologue to his/her story that helps complete the portrait of that person. The story told by the Miller, for example, is just the type of story we expect him to tell because of what we know about his personality. Analyze the elements that make "The Miller's Tale," "The Wife of Bath's Tale," and "The Clerk's Tale" appropriate for those characters.

- After hearing the recordings and seeing the visual examples of the Old English of Beowulf in Chapter 1 and the Middle English of Chaucer, compare and contrast these two precursors of the modern English language.

- Why did Chaucer choose Canterbury Cathedral as the destination for his pilgrims?

Resources: Geoffrey Chaucer (1343–1400)

General Resources

- Chaucer Canterbury Tales. Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. Links to the text, images, audio, and scholarly sources. http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/canterbury.htm

- Chaucer MetaPage. International Congress of Medieval Studies and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Links to the text, images, audio, scholarly sources, and other Chaucer websites. http://englishcomplit.unc.edu/chaucer/index.html

- Geoffrey Chaucer Page. Harvard University. Biographical information, background information, interlinear translations, glossary. http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/

- “Pardoners and Indulgences.” Treasures in Full: Caxton’s Chaucer. British Library. Image of the Pardoner and information on medieval indulgences. http://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/pardoners.html

Biography

- “Chaucer.” Bartleby.com. rpt. from The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21). Volume II. The End of the Middle Ages. http://www.bartleby.com/212/0701.html

- “Chaucer Chronology.” eChaucer: Chaucer in the Twenty-First Century. Gerard NeCastro. University of Maine at Machias. http://www.umm.maine.edu/faculty/necastro/chaucer/chronology/

- “Geoffrey Chaucer (c1343–1400).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt. from A. W. Pollard. "Geoffrey Chaucer." Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed., Vol. VI. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. 17–22. http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/chaucerbio.htm

- “The Life of Chaucer.” Geoffrey Chaucer Page. Harvard University. http://courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/special/varia/life_of_Ch/ch-life.html/

Text in Modern English Translation

- The Canterbury Tales. Michael Murphy. Brooklyn College, City University of New York. “The General Prologue” and selected tales in Middle English with “reader-friendly” prose translations. http://academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu/webcore/murphy/canterbury/canterbury.htm

- “The Canterbury Tales and Other Works.” Librarius. side-by-side translations. http://www.librarius.com/

- “Canterbury Tales: Prologue [Parallel Texts].” Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Paul Halsall. Fordham University. parallel edition of “The General Prologue.” http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/CT-prolog-para.html

- “ELF Presents The Canterbury Tales.” The Electronic Literature Foundation. http://www.canterburytales.org/canterbury_tales.html

- “Interlinear Translations of Some of The Canterbury Tales.” Geoffrey Chaucer Page. L.D. Benson. Harvard University. interlinear translations. http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/teachslf/tr-index.htm

Text in Middle English

- “Chaucer Texts.” eChaucer: Chaucer in the Twenty-First Century. Gerard NeCastro. University of Maine at Machias. Middle English text and prose translations. http://www.umm.maine.edu/faculty/necastro/chaucer/texts/

- The Canterbury Tales, and Other Poems. Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/catalog/world/readfile?fk_files=1448814&pageno=26

- Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=cme;idno=CT

- “Selected Poetry of Geoffrey Chaucer.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English. University of Toronto. http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poet/61.html

Audio

- “The Canterbury Tales.” Ed. D. Laing Purves (1838–1873). Librivox. complete audio files. http://librivox.org/the-canterbury-tales-by-geoffrey-chaucer/

- “The Canterbury Tales Audio Links.” Librarius. selected audio files. http://www.librarius.com/cantlink/audiofs.htm

- “Chaucer Canterbury Tales.” Luminarium. Anniina Jokinen. selected audio files. http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/canterbury.htm

- The Chaucer Metapage Audio Files. Virginia Military Institute. Audio files of “The General Prologue,” “The Knight’s Tale,” “The Miller’s Tale,” “The Wife of Bath’s Tale,” “The Envoy to the Clerk’s Tale,” “The Pardoner’s Tale,” and “The Nun’s Priest Tale.” http://www.vmi.edu/fswebs.aspx?tid=34099&id=34249

Video

- “Geoffrey Chaucer and the Canterbury Tales.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College. http://www.youtube.com/user/DrLoweMCC#p/u/24/2KVcMjtgb8Q

Caxton’s Chaucer

- “Caxton’s Chaucer.” British Library. Online Gallery. Information on and images of Caxton , Caxton’s printing of Chaucer, digital images of Caxton’s editions of Canterbury Tales, links to sources, glossary. http://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/homepage.html

- “Image from William Caxton’s Chaucer.” British Library. Online Gallery. Image of knight and page of print from Caxton’s Chaucer. http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/landprint/chaucer/large17666.html

Manuscripts and Images

- Corpus Christi College. Oxford University. Early 15th-century handwritten manuscript of Canterbury Tales, including unfinished illustrations and notes from the scribe. http://image.ox.ac.uk/show?collection=corpus&manuscript=ms198

- Digital Scriptorium. Huntington Catalog Database. University of California, Berkeley. Images of manuscripts, including the Ellesmere manuscript. http://dpg.lib.berkeley.edu/webdb/dsheh/heh_brf?Description=&CallNumber=EL+26+C+9

- “Geoffrey Chaucer The Canterbury Tales The Classic Text: Traditions and Interpretations.” University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. Information and images of texts and illustrations, including the Ellesmere manuscript and Caxton’s text. http://www4.uwm.edu/libraries/special/exhibits/clastext/clspg073.cfm

- “The World of Chaucer: Medieval Books and Manuscripts.” University of Glasgow exhibit. http://special.lib.gla.ac.uk/exhibns/chaucer/index.html

Concordance

- Chaucer Concordance. eChaucer: Chaucer in the Twenty-First Century. Gerard NeCastro. University of Maine at Machias. http://www.umm.maine.edu/faculty/necastro/chaucer/concordance/

Middle English Dictionary/Glossary

- Chaucer Glossary. eChaucer: Chaucer in the Twenty-First Century. Gerard NeCastro. University of Maine at Machias. http://www.umm.maine.edu/faculty/necastro/chaucer/glossary/

- Middle English Dictionary. University of Michigan. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/med/

1.6 Julian of Norwich (1342–1416)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Define the term showing as used in the Middle Ages and explain why it is an appropriate title for the work of Julian of Norwich.

- Account for the Lady Julian’s writing skill in an age in which illiteracy, particularly among women, was common.

Biography

Little is known of the woman now called Julian of Norwich before she became an anchoressa woman called to a contemplative life closed away from other people, a woman called to a contemplative life closed away from other people. As part of her renunciation of her worldly life, she gave up her birth name and adopted the name Julian from the Church of St. Julian in Norwich, England. Julian of Norwich lived in a small room, typical of anchorites and anchoresses, called a cell attached to the church. Unlike many anchoresses, who often had not taken religious orders, Julian may have been a Benedictine nun before beginning her reclusive life.

St. Julian’s Church, Norwich.

An anchoress’s cell typically had a window that opened into the church proper, allowing the recluse to listen to and participate in worship services. Another window would open into a small room where a servant, who took care of her worldly needs, lived, and a third window opened to the outside to allow the anchoress to converse with people who sought her spiritual guidance.

Lady Julian’s cell and the window opening into the church.

According to her own account, when Julian was thirty years old, she suffered a nearly fatal illness. As she recovered she experienced a series of visions. Deciding to become an anchoress, over the next several years she wrote two versions of her Showings of Love.

Text

“Revelations of Divine Love.” Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Calvin College. http://www.ccel.org/ccel/julian/revelations.html

Showings of Love (also known as Revelations of Divine Love)

Although her work bears various titles, Julian chose the word showinga word used in the Middle Ages to describe a manifestation, a revelation, a dream, or a vision, usually of a religious nature, a word used in the Middle Ages to describe a manifestation, a revelation, a dream, or a vision, usually of a religious nature. Her work encompasses her descriptions and explanations of the spiritual insight gained through a series of spiritual visions and visitations she experienced during her severe illness.

In contrast to the teachings of the medieval church and to commonly held beliefs of the Middle Ages, Julian’s writings emphasize the love and compassion of Christ; unlike most people of that era, Julian did not consider illness or suffering a punishment from God but a means of becoming close to God. Rather than emphasizing the fear of damnation in the next world, Julian hoped that all people would be saved from Hell and would receive the blessing of eternal life with God. Also, Julian metaphorically referred to God as both Father and Mother, in opposition to the medieval Church’s paternalistic view of God as Father.

In one of her more well-known passages, Julian describes holding a hazelnut in the palm of her hand and realizing three things from the experience: 1. that God made it; 2. that God loves it; 3. that God keeps it. Perhaps the most recognized quotation from her work is her saying, “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well.”

The British Library provides a digitized view of a medieval manuscript which includes Julian’s work.

Key Takeaways

- Little is known about Julian of Norwich before she became an anchoress and adopted the name Julian.

- Her major work, Showings of Love, is an explanation of the visions she had during a serious illness.

- Some of Julian’s theology conflicts with the teachings of the medieval Church.

Exercises

- Find the medieval definition of showing from the Oxford English Dictionary, and apply the definition to Julian’s works.

- What, according to her comments, is the significance of Julian’s observations about the hazelnut? What other images or metaphors does Julian of Norwich use to express her spiritual insights?

- What aspects of Julian’s life and writings might contradict the traditional teachings of the medieval Church? Speculate on why the Church did not attempt to suppress her writing or to reprimand her for ideas that, from other individuals, might be considered heretical, such as the idea of God as a Mother figure.

Resources: Julian of Norwich

General Resources

- Julian of Norwich 1342-c.1416. Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. Biographical information, text of Revelations, and scholarly articles. http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/julian.htm

- “Women.” Learning: Medieval Realms. British Library. http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/medieval/women2/medievalwomen.html

Text

- “Revelations of Divine Love.” Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Calvin College. http://www.ccel.org/ccel/julian/revelations.html

Biography

- “The Beginning of Julian’s Spiritual Vision, in a Collection of Theological Works, including Julian of Norwich.” Illuminated Manuscripts. Online Gallery. British Library. http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/illmanus/other/011add000037790u00097v00.html

- “Julian of Norwich.” Karen Rae Keck. The Ecole Glossary. The Ecole Initiative. University of Evansville. Brief biographical information. http://ecole.evansville.edu/glossary/juliann.html