This is “Net Present Value”, section 8.2 from the book Accounting for Managers (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

8.2 Net Present Value

Learning Objective

- Evaluate investments using the net present value (NPV) approach.

Question: Now that we have the tools to calculate the present value of future cash flows, we can use this information to make decisions about long-term investment opportunities. How does this information help companies to evaluate long-term investments?

Answer: The net present value (NPV)A method used to evaluate long-term investments. It is calculated by adding the present value of all cash inflows and subtracting the present value of all cash outflows. method of evaluating investments adds the present value of all cash inflows and subtracts the present value of all cash outflows. The term discounted cash flows is also used to describe the NPV method. In the previous section, we described how to find the present value of a cash flow. The term net in net present value means to combine the present value of all cash flows related to an investment (both positive and negative).

Recall the problem facing Jackson’s Quality Copies at the beginning of the chapter. The company’s president and owner, Julie Jackson, would like to purchase a new copy machine. Julie feels the investment is worthwhile because the cash inflows over the copier’s life total $82,000, and the cash outflows total $57,000, resulting in net cash inflows of $25,000 (= $82,000 – $57,000). However, this approach ignores the timing of the cash flows. We know from the previous section that the further into the future the cash flows occur, the lower the value in today’s dollars.

Question: How do managers adjust for the timing differences related to future cash flows?

Answer: Most managers use the NPV approach. This approach requires three steps to evaluate an investment:

Step 1. Identify the amount and timing of the cash flows required over the life of the investment.

Step 2. Establish an appropriate interest rate to be used for evaluating the investment, typically called the required rate of returnThe interest rate used for evaluating long-term investments; it represents the company’s minimum acceptable return (or discount rate; also called hurdle rate).. (This rate is also called the discount rate or hurdle rate.)

Step 3. Calculate and evaluate the NPV of the investment.

Let’s use Jackson’s Quality Copies as an example to see how this process works.

Step 1. Identify the amount and timing of the cash flows required over the life of the investment.

Question: What are the cash flows associated with the copy machine that Jackson’s Quality Copies would like to buy?

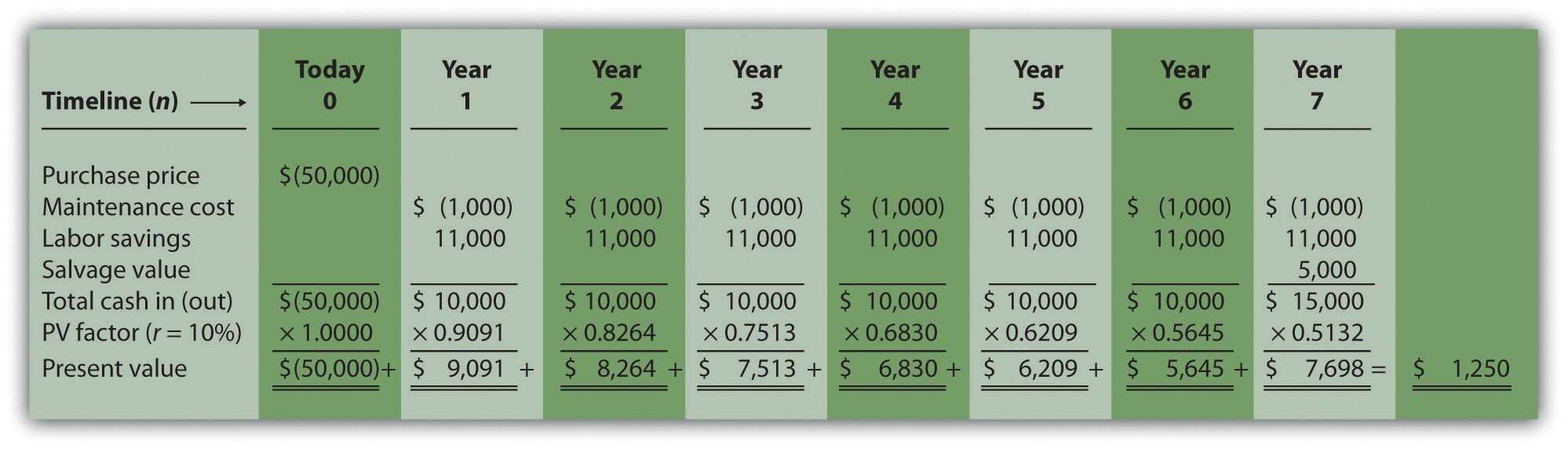

Answer: Jackson’s Quality Copies will pay $50,000 for the new copier, which is expected to last 7 years. Annual maintenance costs will total $1,000 a year, labor cost savings will total $11,000 a year, and the company will sell the copier for $5,000 at the end of 7 years. Figure 8.1 "Cash Flows for Copy Machine Investment by Jackson’s Quality Copies" summarizes the cash flows related to this investment. Amounts in parentheses are cash outflows. All other amounts are cash inflows.

Figure 8.1 Cash Flows for Copy Machine Investment by Jackson’s Quality Copies

Step 2. Establish an appropriate interest rate to be used for evaluating the investment.

Question: How do managers establish the interest rate to be used for evaluating an investment?

Answer: Although managers often estimate the interest rate, this estimate is typically based on the organization’s cost of capital. The cost of capitalThe weighted average costs associated with debt and equity used to fund long-term investments. is the weighted average costs associated with debt and equity used to fund long-term investments. The cost of debt is simply the interest rate associated with the debt (e.g., interest for bank loans or bonds issued). The cost of equity is more difficult to determine and represents the return required by owners of the organization. The weighted average of these two sources of capital represents the cost of capital (finance textbooks address the complexities of this calculation in more detail).

The general rule is the higher the risk of the investment, the higher the required rate of return (assume required rate of return is synonymous with interest rate for the purpose of calculating the NPV). A firm evaluating a long-term investment with risk similar to the firm’s average risk will typically use the cost of capital. However, if a long-term investment carries higher than average risk for the firm, the firm will use a required rate of return higher than the cost of capital.

The accountant at Jackson’s Quality Copies, Mike Haley, has established the cost of capital for the firm at 10 percent. Since the proposed purchase of a copy machine is of average risk to the company, Mike will use 10 percent as the required rate of return.

Step 3. Calculate and evaluate the NPV of the investment.

Question: How do managers calculate the NPV of an investment?

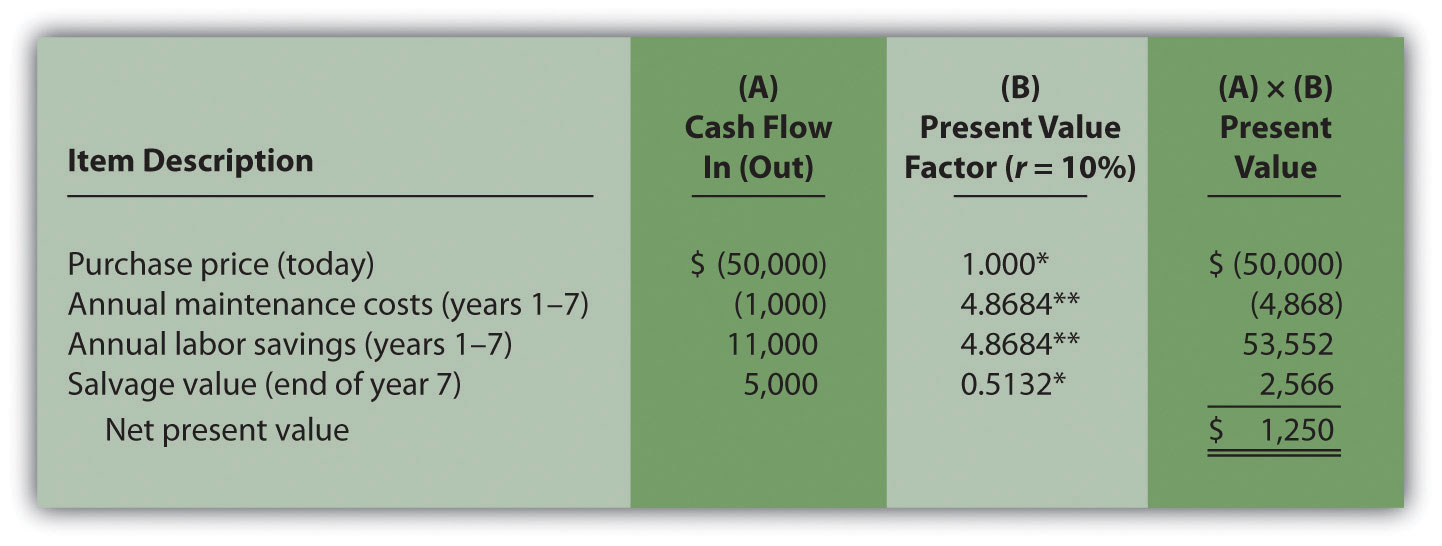

Answer: Figure 8.2 "NPV Calculation for Copy Machine Investment by Jackson’s Quality Copies" shows the NPV calculation for Jackson’s Quality Copies. Examine this table carefully. The cash flows come from Figure 8.1 "Cash Flows for Copy Machine Investment by Jackson’s Quality Copies". The present value factors come from Figure 8.9 "Present Value of $1 Received at the End of " in the appendix (r = 10 percent; n = year). The bottom row, labeled present value is calculated by multiplying the total cash in (out) × present value factor, and it represents total cash flows for each time period in today’s dollars. The bottom right of Figure 8.2 "NPV Calculation for Copy Machine Investment by Jackson’s Quality Copies" shows the NPV for the investment, which is the sum of the bottom row labeled present value.

Figure 8.2 NPV Calculation for Copy Machine Investment by Jackson’s Quality Copies

The NPV is $1,250. Because NPV is > 0, accept the investment. (The investment provides a return greater than 10 percent.)

The NPV Rule

Question: Once the NPV is calculated, how do managers use this information to evaluate a long-term investment?

Answer: Managers apply the following rule to decide whether to proceed with the investment:

NPV Rule: If the NPV is greater than or equal to zero, accept the investment; otherwise, reject the investment.

As summarized in Figure 8.3 "The NPV Rule", if the NPV is greater than zero, the rate of return from the investment is higher than the required rate of return. If the NPV is zero, the rate of return from the investment equals the required rate of return. If the NPV is less than zero, the rate of return from the investment is less than the required rate of return. Since the NPV is greater than zero for Jackson’s Quality Copies, the investment is generating a return greater than the company’s required rate of return of 10 percent.

Figure 8.3 The NPV Rule

Note that the present value calculations in Figure 8.3 "The NPV Rule" assume that the cash flows for years 1 through 7 occur at the end of each year. In reality, these cash flows occur throughout each year. The impact of this assumption on the NPV calculation is typically negligible.

Business in Action 8.2

Cost of Capital by Industry

Cost of capital can be estimated for a single company or for entire industries. New York University’s Stern School of Business maintains cost of capital figures by industry. Almost 7,000 firms were included in accumulating this information. The following sampling of industries compares the cost of capital across industries. Notice that high-risk industries (e.g., computer, e-commerce, Internet, and semiconductor) have relatively high costs of capital.

| Air transportation | 11.48 percent |

| Auto and truck | 11.04 percent |

| Auto parts | 9.56 percent |

| Beverage (soft drinks) | 8.16 percent |

| Computer | 14.49 percent |

| E-commerce | 15.65 percent |

| Grocery | 9.79 percent |

| Internet | 15.98 percent |

| Retail store | 9.30 percent |

| Semiconductor | 19.03 percent |

Source: New York University’s Stern Business School, “Home Page,” http://pages.stern.nyu.edu.

Annuity Tables

Question: Notice in Figure 8.1 "Cash Flows for Copy Machine Investment by Jackson’s Quality Copies" that the rows labeled maintenance cost and labor savings have identical cash flows from one year to the next. Identical cash flows that occur in regular intervals, such as these at Jackson’s Quality Copies, are called an annuityA term used to describe identical cash flows that occur in regular intervals.. How can we use annuities in an alternate format to calculate the NPV?

Answer: In Figure 8.4 "Alternative NPV Calculation for Jackson’s Quality Copies", we demonstrate an alternative approach to calculating the NPV.

Figure 8.4 Alternative NPV Calculation for Jackson’s Quality Copies

*Because this is not an annuity, use Figure 8.9 "Present Value of $1 Received at the End of " in the appendix.

**Because this is an annuity, use Figure 8.10 "Present Value of a $1 Annuity Received at the End of Each Period for " in the appendix. The number of years (n) equals seven since identical cash flows occur each year for seven years.

Note: the NPV of $1,250 is the same as the NPV in Figure 8.2 "NPV Calculation for Copy Machine Investment by Jackson’s Quality Copies".

The purchase price and salvage value rows in Figure 8.4 "Alternative NPV Calculation for Jackson’s Quality Copies" represent one-time cash flows, and thus we use Figure 8.9 "Present Value of $1 Received at the End of " in the appendix to find the present value factor for these items (these are not annuities). The annual maintenance costs and annual labor savings rows represent cash flows that occur each year for seven years (these are annuities). We use Figure 8.10 "Present Value of a $1 Annuity Received at the End of Each Period for " in the appendix to find the present value factor for these items (note that the number of years, n, equals seven since the cash flows occur each year for seven years). Simply multiply the cash flow shown in column (A) by the present value factor shown in column (B) to find the present value for each line item. Then sum the present value column to find the NPV. This alternative approach results in the same NPV shown in Figure 8.2 "NPV Calculation for Copy Machine Investment by Jackson’s Quality Copies".

Business in Action 8.3

© Thinkstock

Winning the Lottery

Like many other states, California pays out lottery winnings in installments over several years. For example, a $1,000,000 lottery winner in California will receive $50,000 each year for 20 years.

Does this mean that the State of California must have $1,000,000 on the day the winner claims the prize? No. In fact, California has approximately $550,000 in cash to pay $1,000,000 over 20 years. This $550,000 in cash represents the present value of a $50,000 annuity lasting 20 years, and the state invests it so that it can provide $1,000,000 to the winner over 20 years.

Source: California State Lottery, “California State Lottery Home Page,” http://www.calottery.com.

Key Takeaway

- Present value calculations tell us the value of cash flows in today’s dollars. The NPV method adds the present value of all cash inflows and subtracts the present value of all cash outflows related to a long-term investment. If the NPV is greater than or equal to zero, accept the investment; otherwise, reject the investment.

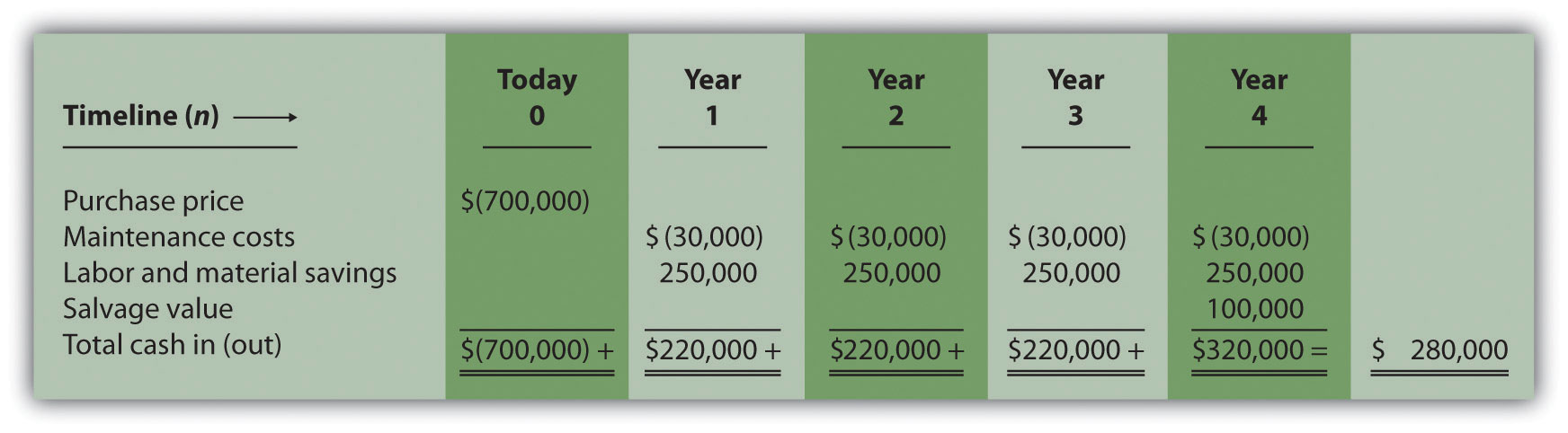

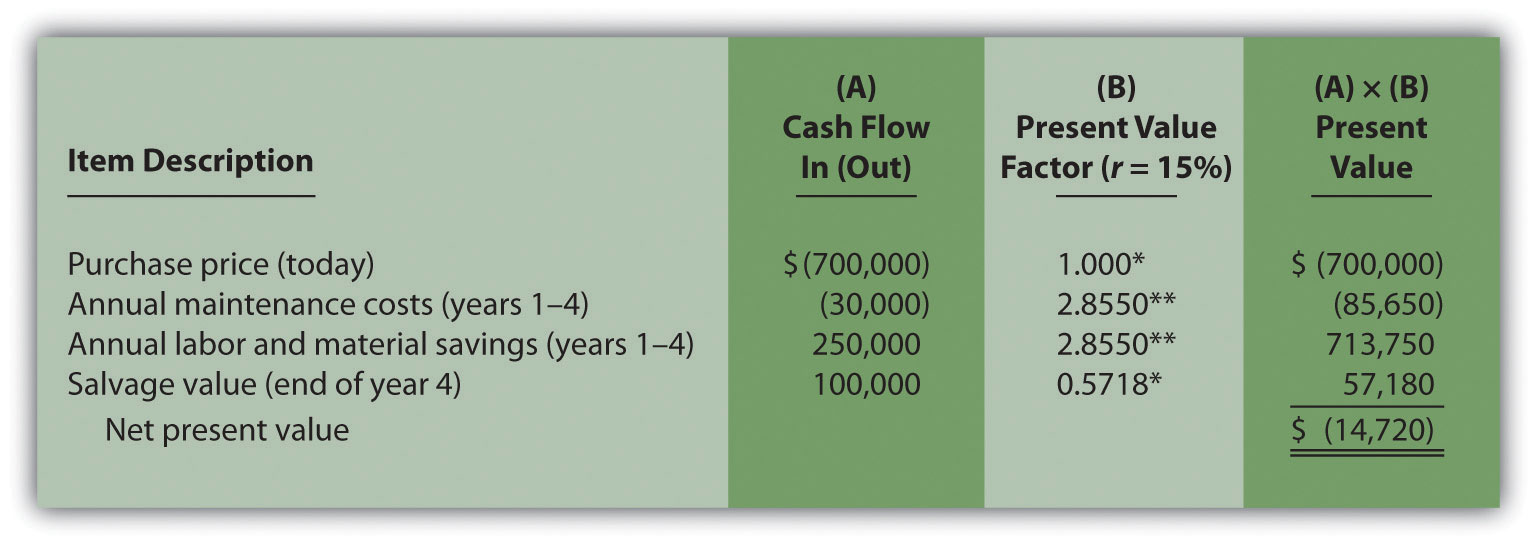

Review Problem 8.2

The management of Chip Manufacturing, Inc., would like to purchase a specialized production machine for $700,000. The machine is expected to have a life of 4 years, and a salvage value of $100,000. Annual maintenance costs will total $30,000. Annual labor and material savings are predicted to be $250,000. The company’s required rate of return is 15 percent.

- Ignoring the time value of money, calculate the net cash inflow or outflow resulting from this investment opportunity.

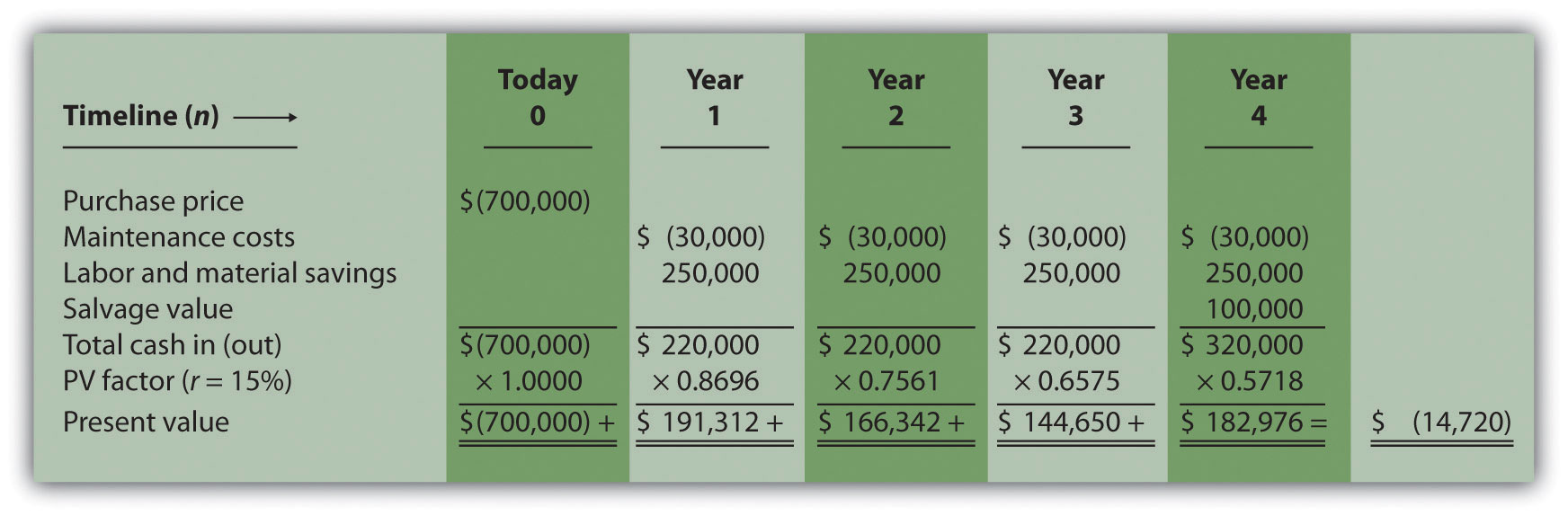

- Find the NPV of this investment using the format presented in Figure 8.2 "NPV Calculation for Copy Machine Investment by Jackson’s Quality Copies".

- Find the NPV of this investment using the format presented in Figure 8.4 "Alternative NPV Calculation for Jackson’s Quality Copies".

- Should Chip Manufacturing, Inc., purchase the specialized production machine? Explain.

Solution to Review Problem 8.2

-

The net cash inflow, ignoring the time value of money, is $280,000, calculated as follows:

-

The NPV is $(14,720), calculated as follows:

-

The alternative format used for calculating the NPV is shown as follows. Note that the NPV here is identical to the NPV calculated previously in part 2.

*Because this is not an annuity, use Figure 8.9 "Present Value of $1 Received at the End of " in the appendix.

**Because this is an annuity, use Figure 8.10 "Present Value of a $1 Annuity Received at the End of Each Period for " in the appendix. The number of years (n) equals four since identical cash flows occur each year for four years.

- Because the NPV is less than 0, the return generated by this investment is less than the company’s required rate of return of 15 percent. Thus Chip Manufacturing, Inc., should not purchase the specialized production machine.