This is “Preparing a Speech”, chapter 9 from the book A Primer on Communication Studies (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 9 Preparing a Speech

Ancient Greek educators and philosophers wrote the first public speaking texts about 2,400 years ago. Aristotle’s On Rhetoric covers many of the same topics addressed in this unit of the book, including speech organization, audience analysis, and persuasive appeals. Even though these principles have been around for thousands of years and have been taught to millions of students, it’s still a challenge to get students to see the value of public speaking. Some students think they already know everything they need to know about speaking in public. In response I remind them that even the best speakers still don’t know everything there is to know about public speaking. Other students don’t think they’ll engage in public speaking very often, if at all. To them, I mention that oral communication and presentation skills are integral to professional and personal success. Last, some students are anxious or even scared by the thought of speaking in front of an audience. To them, I explain that speaking anxiety is common and can be addressed. Learning about and practicing public speaking fosters transferable skills that will help you organize your thoughts, outline information, do research, adapt to various audiences, and utilize and understand persuasive techniques. These skills will be useful in other college classes, your career, your personal relationships, and your civic life.

9.1 Selecting and Narrowing a Topic

Learning Objectives

- Employ audience analysis.

- Determine the general purpose of a speech.

- List strategies for narrowing a speech topic.

- Compose an audience-centered, specific purpose statement for a speech.

- Compose a thesis statement that summarizes the central idea of a speech.

There are many steps that go into the speech-making process. Many people do not approach speech preparation in an informed and systematic way, which results in many poorly planned or executed speeches that are not pleasant to sit through as an audience member and don’t reflect well on the speaker. Good speaking skills can help you stand out from the crowd in increasingly competitive environments. While a polished delivery is important and will be discussed more in Chapter 10 "Delivering a Speech", good speaking skills must be practiced much earlier in the speech-making process.

Analyze Your Audience

Audience analysis is key for a speaker to achieve his or her speech goal. One of the first questions you should ask yourself is “Who is my audience?” While there are some generalizations you can make about an audience, a competent speaker always assumes there is a diversity of opinion and background among his or her listeners. You can’t assume from looking that everyone in your audience is the same age, race, sexual orientation, religion, or many other factors. Even if you did have a fairly homogenous audience, with only one or two people who don’t match up, you should still consider those one or two people. When I have a class with one or two older students, I still consider the different age demographics even though twenty other students are eighteen to twenty-two years old. In short, a good speaker shouldn’t intentionally alienate even one audience member. Of course, a speaker could still unintentionally alienate certain audience members, especially in persuasive speaking situations. While this may be unavoidable, speakers can still think critically about what content they include in the speech and the effects it may have.

Good speakers should always assume a diversity of backgrounds and opinions among their audience members.

© Thinkstock

Even though you should remain conscious of the differences among audience members, you can also focus on commonalities. When delivering a speech in a college classroom, you can rightfully assume that everyone in your audience is currently living in the general area of the school, is enrolled at the school, and is currently taking the same speech class. In professional speeches, you can often assume that everyone is part of the same professional organization if you present at a conference, employed at the same place or in the same field if you are giving a sales presentation, or experiencing the nervousness of starting a new job if you are leading an orientation or training. You may not be able to assume much more, but that’s enough to add some tailored points to your speech that will make the content more relevant.

Demographic Audience Analysis

DemographicsBroad sociocultural categories such as age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, education level, religion, ethnicity, and nationality that are used to segment a larger population. are broad sociocultural categories, such as age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, education level, religion, ethnicity, and nationality that are used to segment a larger population. Since you are always going to have diverse demographics among your audience members, it would be unwise to focus solely on one group over another. As a speaker, being aware of diverse demographics is useful in that you can tailor and vary examples to appeal to different groups of people. As you can read in the “Getting Real” feature in this chapter, engaging in audience segmentation based on demographics is much more targeted in some careers.

Psychological Audience Analysis

Psychological audience analysisAnalysis that considers your audience’s psychological dispositions toward the topic, speaker, and occasion and how their attitudes, beliefs, and values inform those dispositions. considers your audience’s psychological dispositions toward the topic, speaker, and occasion and how their attitudes, beliefs, and values inform those dispositions. When considering your audience’s disposition toward your topic, you want to assess your audience’s knowledge of the subject. You wouldn’t include a lesson on calculus in an introductory math course. You also wouldn’t go into the intricacies of a heart transplant to an audience with no medical training. A speech on how to give a speech would be redundant in a public speaking class, but it could be useful for high school students or older adults who are going through a career transition. Students in my class recently had to theme their informative speeches around the topic of renewable energy. They were able to tie their various topics to a new renewable energy production plant that opened that semester on our campus. They had to be careful not to overrun their speech with scientific jargon. One student compared the concept of biogasification to the natural gas production that comes from living creatures like humans and cows. This comparison got a laugh from the audience and also made the seemingly complex concept more understandable.

The audience may or may not have preconceptions about you as a speaker. One way to positively engage your audience is to make sure you establish your credibility. In terms of credibilityAudience members’ perceptions of whether or not a speaker is competent, trustworthy, and/or engaging., you want the audience to see you as competent, trustworthy, and engaging. If the audience is already familiar with you, they may already see you as a credible speaker because they’ve seen you speak before, have heard other people evaluate you positively, or know that you have credentials and/or experience that make you competent. If you know you have a reputation that isn’t as positive, you will want to work hard to overcome those perceptions. To establish your trustworthiness, you want to incorporate good supporting material into your speech, verbally cite sources, and present information and arguments in a balanced, noncoercive, and nonmanipulative way. To establish yourself as engaging, you want to have a well-delivered speech, which requires you to practice, get feedback, and practice some more. Your verbal and nonverbal delivery should be fluent and appropriate to the audience and occasion. We will discuss speech delivery more in Chapter 10 "Delivering a Speech".

The circumstances that led your audience to attend your speech will affect their view of the occasion. A captive audienceAn audience consisting of people who are required to be present. includes people who are required to attend your presentation. Mandatory meetings are common in workplace settings. Whether you are presenting for a group of your employees, coworkers, classmates, or even residents in your dorm if you are a resident advisor, you shouldn’t let the fact that the meeting is required give you license to give a half-hearted speech. In fact, you may want to build common ground with your audience to overcome any potential resentment for the required gathering. In your speech class, your classmates are captive audience members.

When you speak in a classroom or at a business meeting, you may have a captive audience.

©Thinkstock

View having a captive classroom audience as a challenge, and use this space as a public speaking testing laboratory. You can try new things and push your boundaries more, because this audience is very forgiving and understanding since they have to go through the same things you do. In general, you may have to work harder to maintain the attention of a captive audience. Since coworkers may expect to hear the same content they hear every time this particular meeting comes around, and classmates have to sit through dozens and dozens of speeches, use your speech as an opportunity to stand out from the crowd or from what’s been done before.

A voluntary audienceAn audience consisting of people who chose to be present. includes people who have decided to come hear your speech. This is perhaps one of the best compliments a speaker can receive, even before they’ve delivered the speech. Speaking for a voluntary audience often makes me have more speaking anxiety than I do when speaking in front of my class or my colleagues, because I know the audience may have preconceived notions or expectations that I must live up to. This is something to be aware of if you are used to speaking in front of captive audiences. To help adapt to a voluntary audience, ask yourself what the audience members expect. Why are they here? If they’ve decided to come and see you, they must be interested in your topic or you as a speaker. Perhaps you have a reputation for being humorous, being able to translate complicated information into more digestible parts, or being interactive with the audience and responding to questions. Whatever the reason or reasons, it’s important to make sure you deliver on those aspects. If people are voluntarily giving up their time to hear you, you want to make sure they get what they expected.

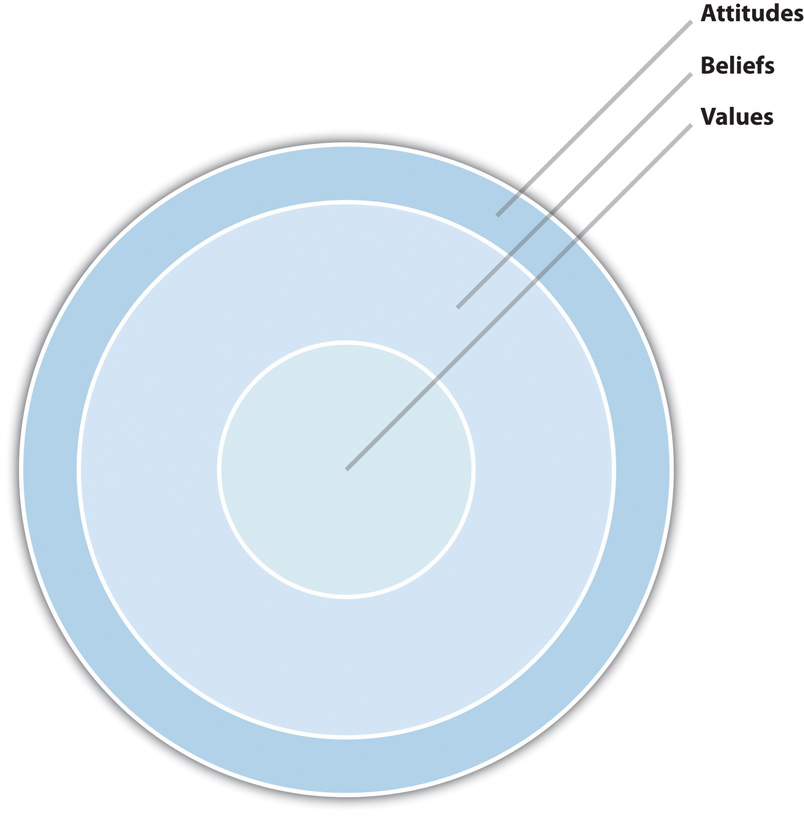

A final aspect of psychological audience analysis involves considering the audience’s attitudes, beliefs, and values, as they will influence all the perceptions mentioned previously. As you can see in Figure 9.1 "Psychological Analysis: Attitudes, Beliefs, and Values", we can think of our attitudes, beliefs, and values as layers that make up our perception and knowledge.

Figure 9.1 Psychological Analysis: Attitudes, Beliefs, and Values

At the outermost level, attitudes are our likes and dislikes, and they are easier to influence than beliefs or values because they are often reactionary. If you’ve ever followed the approval rating of a politician, you know that people’s likes and dislikes change frequently and can change dramatically based on recent developments. This is also true interpersonally. For those of you who have siblings, think about how you can go from liking your sisters or brothers, maybe because they did something nice for you, to disliking them because they upset you. This seesaw of attitudes can go up and down over the course of a day or even a few minutes, but it can still be useful for a speaker to consider. If there is something going on in popular culture or current events that has captured people’s attention and favor or disfavor, then you can tap into that as a speaker to better relate to your audience.

When considering beliefs, we are dealing with what we believe “is or isn’t” or “true or false.” We come to hold our beliefs based on what we are taught, experience for ourselves, or have faith in. Our beliefs change if we encounter new information or experiences that counter previous ones. As people age and experience more, their beliefs are likely to change, which is natural.

Our values deal with what we view as right or wrong, good or bad. Our values do change over time but usually as a result of a life transition or life-changing event such as a birth, death, or trauma. For example, when many people leave their parents’ control for the first time and move away from home, they have a shift in values that occurs as they make this important and challenging life transition. In summary, audiences enter a speaking situation with various psychological dispositions, and considering what those may be can help speakers adapt their messages and better meet their speech goals.

Situational Audience Analysis

Situational audience analysisAnalysis that considers the physical surroundings and setting of a speech. considers the physical surroundings and setting of a speech. It’s always a good idea to visit the place you will be speaking ahead of time so you will know what to expect. If you expect to have a lectern and arrive to find only a table at the front of the room, that little difference could end up increasing your anxiety and diminishing your speaking effectiveness. I have traveled to many different universities, conference facilities, and organizations to speak, and I always ask my host to show me the room I will be speaking in. I take note of the seating arrangement, the presence of technology and its compatibility with what I plan on using, the layout of the room including windows and doors, and anything else that’s relevant to my speech. Knowing your physical setting ahead of time allows you to alter the physical setting, when possible, or alter your message or speaking strategies if needed. Sometimes I open or close blinds, move seats around, plug my computer in to make sure it works, or even practice some or all of my presentation. I have also revised a speech to be more interactive and informal when I realized I would speak in a lounge rather than a classroom or lecture hall.

“Getting Real”

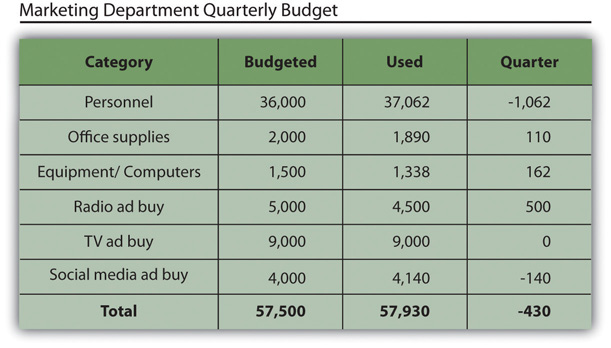

Marketing Careers and Audience Segmentation

Advertisers and marketers use sophisticated people and programs to ensure that their message is targeted to particular audiences. These people are often called marketing specialists.Career Cruising, “Marketing Specialist,” Career Cruising: Explore Careers, accessed January 24, 2012, http://www.careercruising.com. They research products and trends in markets and consumer behaviors and may work for advertising agencies, marketing firms, consulting firms, or other types of agencies or businesses. The pay range is varied, from $35,000 to $166,000 a year for most, and good communication, creativity, and analytic thinking skills are a must. If you stop to think about it, we are all targeted based on our demographics, psychographics, and life situations. Whereas advertisers used to engage in more mass marketing, to undifferentiated receivers, the categories are now much more refined and the target audiences more defined. We only need to look at the recent increase in marketing toward “tweens” or the eight-to-twelve age group. Although this group was once lumped in with younger kids or older teens, they are now targeted because they have “more of their own money to spend and more influence over familial decisions than ever before.”David L. Siegel, Timothy J. Coffey, and Gregory Livingston, The Great Tween Buying Machine (Chicago, IL: Dearborn Trade, 2004).

Whether it’s Red Bull aggressively marketing to the college-aged group or gyms marketing to single, working, young adults, much thought and effort goes into crafting a message with a particular receiver in mind. Some companies even create an “ideal customer,” going as far as to name the person, create a psychological and behavioral profile for them, and talk about them as if they were real during message development.Michael R. Solomon, Consumer Behavior: Buying, Having, and Being, 7th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2006), 10–11.

Facebook has also revolutionized targeted marketing, which has led to some controversy and backlash.Daisy Greenwell, “You Might Not ‘Like’ Facebook So Much after Reading This…” The Times (London), sec. T2, January 13, 2012, 4–5. The “Like” button on Facebook that was introduced in 2010 is now popping up on news sites, company pages, and other websites. When you click the “Like” button, you are providing important information about your consumer behaviors that can then be fed into complicated algorithms that also incorporate demographic and psychographic data pulled from your Facebook profile and even information from your friends. All this is in an effort to more directly market to you, which became easier in January of 2012 when Facebook started allowing targeted advertisements to go directly into users’ “newsfeeds.”

Markets are obviously segmented based on demographics like gender and age, but here are some other categories and examples of market segments: geography (region, city size, climate), lifestyle (couch potato, economical/frugal, outdoorsy, status seeker), family life cycle (bachelors, newlyweds, full nesters, empty nesters), and perceived benefit of use (convenience, durability, value for the money, social acceptance), just to name a few.Leon G. Schiffman and Leslie Lazar Kanuk, Consumer Behavior, 7th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2000), 37.

- Make a list of the various segments you think marketers might put you in. Have you ever thought about these before? Why or why not?

- Take note of the advertisements that catch your eye over a couple days. Do they match up with any of the segments you listed in the first question?

- Are there any groups that you think it would be unethical to segment and target for marketing? Explain your answer.

Determine Your Purpose, Topic, and Thesis

General Purpose

Your speeches will usually fall into one of three categories. In some cases we speak to inform, meaning we attempt to teach our audience using factual objective evidence. In other cases, we speak to persuade, as we try to influence an audience’s beliefs, attitudes, values, or behaviors. Last, we may speak to entertain or amuse our audience. In summary, the general purposeThe overarching purpose of your speech, which will be to inform, to persuade, or to entertain. of your speech will be to inform, to persuade, or to entertain.

You can see various topics that may fit into the three general purposes for speaking in Table 9.1 "General Purposes and Speech Topics". Some of the topics listed could fall into another general purpose category depending on how the speaker approached the topic, or they could contain elements of more than one general purpose. For example, you may have to inform your audience about your topic in one main point before you can persuade them, or you may include some entertaining elements in an informative or persuasive speech to help make the content more engaging for the audience. There should not be elements of persuasion included in an informative speech, however, since persuading is contrary to the objective approach that defines an informative general purpose. In any case, while there may be some overlap between general purposes, most speeches can be placed into one of the categories based on the overall content of the speech.

Table 9.1 General Purposes and Speech Topics

| To Inform | To Persuade | To Entertain |

|---|---|---|

| Civil rights movement | Gun control | Comedic monologue |

| Renewable energy | Privacy rights | My craziest adventure |

| Reality television | Prison reform | A “roast” |

Choosing a Topic

Once you have determined (or been assigned) your general purpose, you can begin the process of choosing a topic. In this class, you may be given the option to choose any topic for your informative or persuasive speech, but in most academic, professional, and personal settings, there will be some parameters set that will help guide your topic selection. Speeches in future classes will likely be organized around the content being covered in the class. Speeches delivered at work will usually be directed toward a specific goal such as welcoming new employees, informing about changes in workplace policies, or presenting quarterly sales figures. We are also usually compelled to speak about specific things in our personal lives, like addressing a problem at our child’s school by speaking out at a school board meeting. In short, it’s not often that you’ll be starting from scratch when you begin to choose a topic.

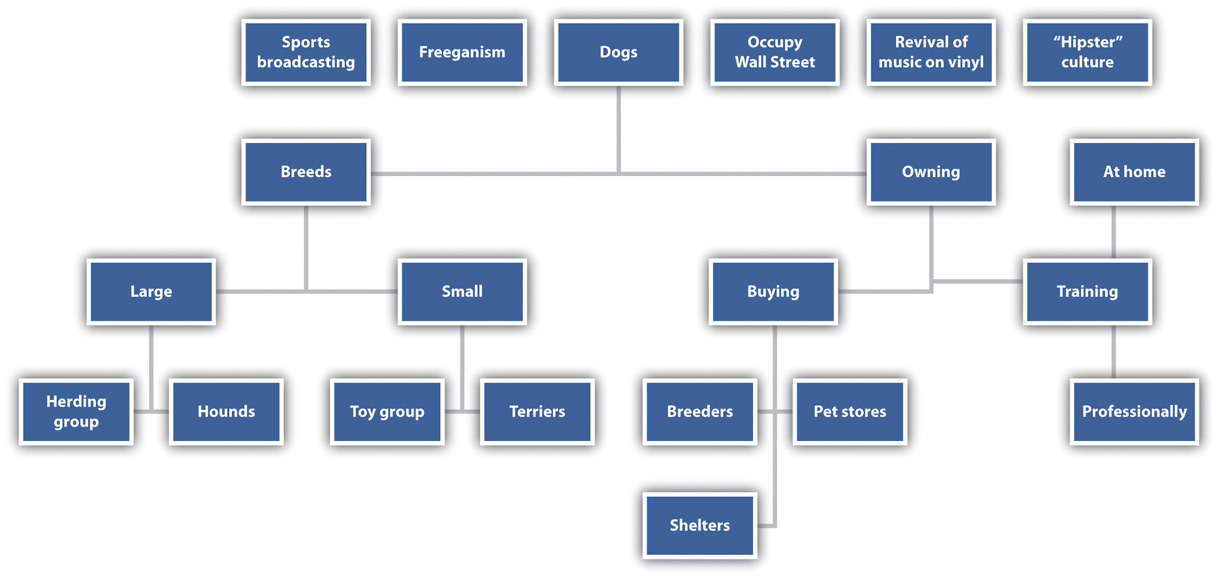

Whether you’ve received parameters that narrow your topic range or not, the first step in choosing a topic is brainstorming. BrainstormingProcess of quickly generating ideas without prejudging them. involves generating many potential topic ideas in a fast-paced and nonjudgmental manner. Brainstorming can take place multiple times as you narrow your topic. For example, you may begin by brainstorming a list of your personal interests that can then be narrowed down to a speech topic. It makes sense that you will enjoy speaking about something that you care about or find interesting. The research and writing will be more interesting, and the delivery will be easier since you won’t have to fake enthusiasm for your topic. Speaking about something you’re familiar with and interested in can also help you manage speaking anxiety. While it’s good to start with your personal interests, some speakers may get stuck here if they don’t feel like they can make their interests relevant to the audience. In that case, you can look around for ideas. If your topic is something that’s being discussed in newspapers, on television, in the lounge of your dorm, or around your family’s dinner table, then it’s likely to be of interest and be relevant since it’s current. Figure 9.1 "Psychological Analysis: Attitudes, Beliefs, and Values" shows how brainstorming works in stages. A list of topics that interest the speaker are on the top row. The speaker can brainstorm subtopics for each idea to see which one may work the best. In this case, the speaker could decide to focus his or her informative speech on three common ways people come to own dogs: through breeders, pet stores, or shelters.

Figure 9.2 Brainstorming and Narrowing a Topic

Overall you can follow these tips as you select and narrow your topic:

- Brainstorm topics that you are familiar with, interest you, and/or are currently topics of discussion.

- Choose a topic appropriate for the assignment/occasion.

- Choose a topic that you can make relevant to your audience.

- Choose a topic that you have the resources to research (access to information, people to interview, etc.).

Specific Purpose

Once you have brainstormed, narrowed, and chosen your topic, you can begin to draft your specific purpose statement. Your specific purposeA one-sentence statement that is audience centered and includes the objective a speaker wants to accomplish in his or her speech. is a one-sentence statement that includes the objective you want to accomplish in your speech. You do not speak aloud your specific purpose during your speech; you use it to guide your researching, organizing, and writing. A good specific purpose statement is audience centered, agrees with the general purpose, addresses one main idea, and is realistic.

An audience-centered specific purpose statement usually contains an explicit reference to the audience—for example, “my audience” or “the audience.” Since a speaker may want to see if he or she effectively met his or her specific purpose, the objective should be written in such a way that it could be measured or assessed, and since a speaker actually wants to achieve his or her speech goal, the specific purpose should also be realistic. You won’t be able to teach the audience a foreign language or persuade an atheist to Christianity in a six- to nine-minute speech. The following is a good example of a good specific purpose statement for an informative speech: “By the end of my speech, the audience will be better informed about the effects the green movement has had on schools.” The statement is audience centered and matches with the general purpose by stating, “the audience will be better informed.” The speaker could also test this specific purpose by asking the audience to write down, at the end of the speech, three effects the green movement has had on schools.

Thesis Statement

Your thesis statementA one-sentence summary of the central idea of your speech that you will either explain or defend. is a one-sentence summary of the central idea of your speech that you either explain or defend. You would explain the thesis statement for an informative speech, since these speeches are based on factual, objective material. You would defend your thesis statement for a persuasive speech, because these speeches are argumentative and your thesis should clearly indicate a stance on a particular issue. In order to make sure your thesis is argumentative and your stance clear, it is helpful to start your thesis with the words “I believe.” When starting to work on a persuasive speech, it can also be beneficial to write out a counterargument to your thesis to ensure that it is arguable.

The thesis statement is different from the specific purpose in two main ways. First, the thesis statement is content centered, while the specific purpose statement is audience centered. Second, the thesis statement is incorporated into the spoken portion of your speech, while the specific purpose serves as a guide for your research and writing and an objective that you can measure. A good thesis statement is declarative, agrees with the general and specific purposes, and focuses and narrows your topic. Although you will likely end up revising and refining your thesis as you research and write, it is good to draft a thesis statement soon after drafting a specific purpose to help guide your progress. As with the specific purpose statement, your thesis helps ensure that your research, organizing, and writing are focused so you don’t end up wasting time with irrelevant materials. Keep your specific purpose and thesis statement handy (drafting them at the top of your working outline is a good idea) so you can reference them often. The following examples show how a general purpose, specific purpose, and thesis statement match up with a topic area:

-

Topic: My Craziest Adventure

General purpose: To Entertain

Specific purpose: By the end of my speech, the audience will appreciate the lasting memories that result from an eighteen-year-old visiting New Orleans for the first time.

Thesis statement: New Orleans offers young tourists many opportunities for fun and excitement.

-

Topic: Renewable Energy

General purpose: To Inform

Specific purpose: By the end of my speech, the audience will be able to explain the basics of using biomass as fuel.

Thesis statement: Biomass is a renewable resource that releases gases that can be used for fuel.

-

Topic: Privacy Rights

General purpose: To Persuade

Specific purpose: By the end of my speech, my audience will believe that parents should not be able to use tracking devices to monitor their teenage child’s activities.

Thesis statement: I believe that it is a violation of a child’s privacy to be electronically monitored by his or her parents.

Key Takeaways

- Getting integrated: Public speaking training builds transferrable skills that are useful in your college classes, career, personal relationships, and civic life.

- Demographic, psychographic, and situational audience analysis help tailor your speech content to your audience.

- The general and specific purposes of your speech are based on the speaking occasion and include the objective you would like to accomplish by the end of your speech. Determining these early in the speech-making process will help focus your research and writing.

- Brainstorm to identify topics that fit within your interests, and then narrow your topic based on audience analysis and the guidelines provided.

- A thesis statement summarizes the central idea of your speech and will be explained or defended using supporting material. Referencing your thesis statement often will help ensure that your speech is coherent.

Exercises

- Getting integrated: Why do some people dread public speaking or just want to avoid it? Identify some potential benefits of public speaking in academic, professional, personal, and civic contexts that might make people see public speaking in a different light.

- Conduct some preliminary audience analysis of your class and your classroom. What are some demographics that might be useful for you to consider? What might be some attitudes, beliefs, and values people have that might be relevant to your speech topics? What situational factors might you want to consider before giving your speech?

- Pay attention to the news (in the paper, on the Internet, television, or radio). Identify two informative and two persuasive speech topics that are based in current events.

9.2 Researching and Supporting Your Speech

Learning Objectives

- Identify appropriate methods for conducting college-level research.

- Distinguish among various types of sources.

- Evaluate the credibility of sources.

- Identify various types of supporting material.

- Employ visual aids that enhance a speaker’s message.

We live in an age where access to information is more convenient than ever before. The days of photocopying journal articles in the stacks of the library or looking up newspaper articles on microfilm are over for most. Yet, even though we have all this information at our fingertips, research skills are more important than ever. Our challenge now is not accessing information but discerning what information is credible and relevant. Even though it may sound inconvenient to have to physically go to the library, students who did research before the digital revolution did not have to worry as much about discerning. If you found a source in the library, you could be assured of its credibility because a librarian had subscribed to or purchased that content. When you use Internet resources like Google or Wikipedia, you have no guarantees about some of the content that comes up.

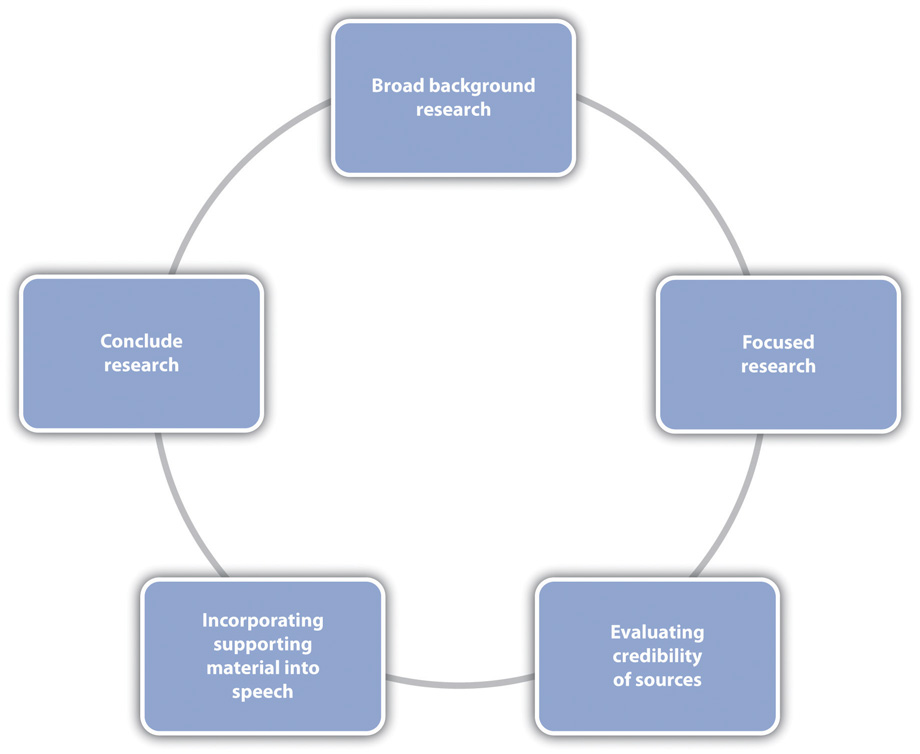

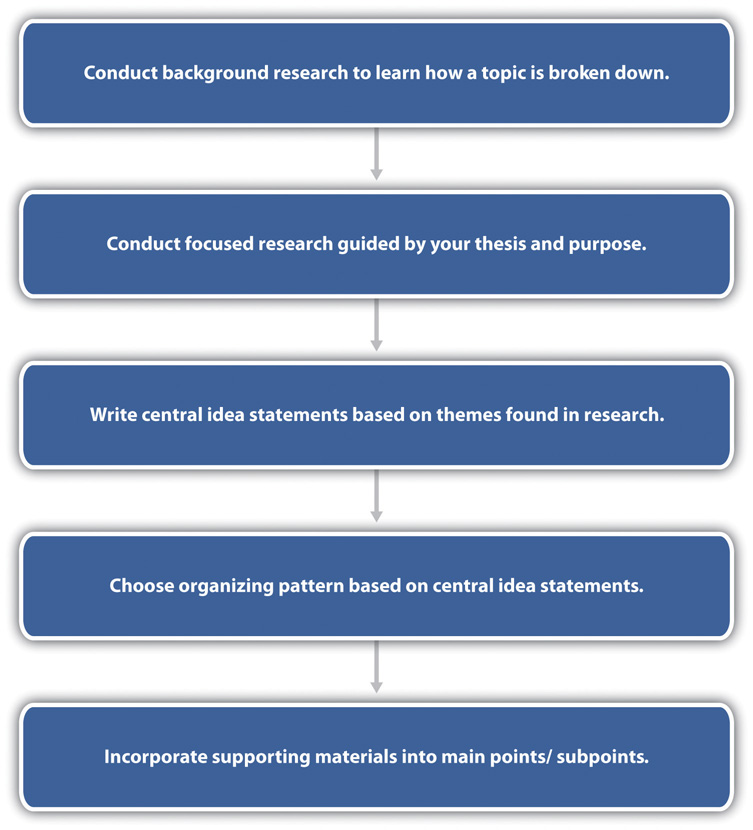

Finding Supporting Material

As was noted in Section 9.1 "Selecting and Narrowing a Topic", it’s good to speak about something you are already familiar with. So existing knowledge forms the first step of your research process. Depending on how familiar you are with a topic, you will need to do more or less background research before you actually start incorporating sources to support your speech. Background research is just a review of summaries available for your topic that helps refresh or create your knowledge about the subject. It is not the more focused and academic research that you will actually use to support and verbally cite in your speech. Figure 9.3 "Research Process" illustrates the research process. Note that you may go through some of these steps more than once.

Figure 9.3 Research Process

I will reiterate several times in this chapter that your first step for research in college should be library resources, not Google or Bing or other general search engines. In most cases, you can still do your library research from the comfort of a computer, which makes it as accessible as Google but gives you much better results. Excellent and underutilized resources at college and university libraries are reference librarians. Reference librariansInformation-retrieval experts at college and university libraries. are not like the people who likely staffed your high school library. They are information-retrieval experts. At most colleges and universities, you can find a reference librarian who has at least a master’s degree in library and information sciences, and at some larger or specialized schools, reference librarians have doctoral degrees. I liken research to a maze, and reference librarians can help you navigate the maze. There may be dead ends, but there’s always another way around to reach the end goal. Unfortunately, many students hit their first dead end and give up or assume that there’s not enough research out there to support their speech. Trust me, if you’ve thought of a topic to do your speech on, someone else has thought of it, too, and people have written and published about it. Reference librarians can help you find that information. I recommend that you meet with a reference librarian face-to-face and take your assignment sheet and topic idea with you. In most cases, students report that they came away with more information than they needed, which is good because you can then narrow that down to the best information. If you can’t meet with a reference librarian face-to-face, many schools now offer the option to do a live chat with a reference librarian, and you can also contact them by e-mail or phone.

College and university libraries are often at the cutting edge of information retrieval for academic research.

©Thinkstock

Aside from the human resources available in the library, you can also use electronic resources such as library databases. Library databases help you access more credible and scholarly information than what you will find using general Internet searches. These databases are quite expensive, and you can’t access them as a regular citizen without paying for them. Luckily, some of your tuition dollars go to pay for subscriptions to these databases that you can then access as a student. Through these databases, you can access newspapers, magazines, journals, and books from around the world. Of course, libraries also house stores of physical resources like DVDs, books, academic journals, newspapers, and popular magazines. You can usually browse your library’s physical collection through an online catalog search. A trip to the library to browse is especially useful for books. Since most university libraries use the Library of Congress classification system, books are organized by topic. That means if you find a good book using the online catalog and go to the library to get it, you should take a moment to look around that book, because the other books in that area will be topically related. On many occasions, I have used this tip and gone to the library for one book but left with several.

Although Google is not usually the best first stop for conducting college-level research, Google Scholar is a separate search engine that narrows results down to scholarly materials. This version of Google has improved much over the past few years and has served as a good resource for my research, even for this book. A strength of Google Scholar is that you can easily search for and find articles that aren’t confined to a particular library database. Basically, the pool of resources you are searching is much larger than what you would have using a library database. The challenge is that you have no way of knowing if the articles that come up are available to you in full-text format. As noted earlier, most academic journal articles are found in databases that require users to pay subscription fees. So you are often only able to access the abstracts of articles or excerpts from books that come up in a Google Scholar search. You can use that information to check your library to see if the article is available in full-text format, but if it isn’t, you have to go back to the search results. When you access Google Scholar on a campus network that subscribes to academic databases, however, you can sometimes click through directly to full-text articles. Although this resource is still being improved, it may be a useful alternative or backup when other search strategies are leading to dead ends.

Types of Sources

There are several different types of sources that may be relevant for your speech topic. Those include periodicals, newspapers, books, reference tools, interviews, and websites. It is important that you know how to evaluate the credibility of each type of source material.

Periodicals

PeriodicalsInformation sources like academic journals and magazines. include magazines and journals, as they are published periodically. There are many library databases that can access periodicals from around the world and from years past. A common database is Academic Search Premiere (a similar version is Academic Search Complete). Many databases, like this one, allow you to narrow your search terms, which can be very helpful as you try to find good sources that are relevant to your topic. You may start by typing a key word into the first box and searching. Sometimes a general search like this can yield thousands of results, which you obviously wouldn’t have time to look through. In this case you may limit your search to results that have your keyword in the abstractAn author-supplied summary of an academic article., which is the author-supplied summary of the source. If there are still too many results, you may limit your search to results that have your keyword in the title. At this point, you may have reduced those ten thousand results down to a handful, which is much more manageable.

Within your search results, you will need to distinguish between magazines and academic journals. In general, academic journals are considered more scholarly and credible than magazines because most of the content in them is peer reviewed. The peer-review processA rigorous form of review that takes several months to years and ensures that the information published has been vetted and approved by numerous experts on the subject. is the most rigorous form of review, which takes several months to years and ensures that the information that is published has been vetted and approved by numerous experts on the subject. Academic journals are usually affiliated with professional organizations rather than for-profit corporations, and neither authors nor editors are paid for their contributions. For example, the Quarterly Journal of Speech is one of the oldest journals in communication studies and is published by the National Communication Association.

The National Communication Association publishes several peer-reviewed academic journals.

Source: Courtesy of the National Communication Association.

If your instructor wants you to have sources from academic journals, you can often click a box to limit your search results to those that are “peer reviewed.” There are also subject-specific databases you can use to find periodicals. For example, Communication and Mass Media Complete is a database that includes articles from hundreds of journals related to communication studies. It may be acceptable for you to include magazine sources in your speech, but you should still consider the credibility of the source. Magazines like Scientific American and Time are generally more credible and reliable than sources like People or Entertainment Weekly.

Newspapers and Books

Newspapers and books can be excellent sources but must still be evaluated for relevance and credibility. Newspapers are good for topics that are developing quickly, as they are updated daily. While there are well-known newspapers of record like the New York Times, smaller local papers can also be credible and relevant if your speech topic doesn’t have national or international reach. You can access local, national, and international newspapers through electronic databases like LexisNexis. If a search result comes up that doesn’t have a byline with an author’s name or an organization like the Associated Press or Reuters cited, then it might be an editorial. Editorials may also have bylines, which make them look like traditional newspaper articles even though they are opinion based. It is important to distinguish between news articles and editorials because editorials are usually not objective and do not go through the same review process that a news story does before it’s published. It’s also important to know the background of your paper. Some newspapers are more tabloid focused or may be published by a specific interest group that has an agenda and biases. So it’s usually better to go with a newspaper that is recognized as the newspaper of record for a particular area.

Books are good for a variety of subjects and are useful for in-depth research that you can’t get as regularly from newspapers or magazines. Edited books with multiple chapters by different authors can be especially good to get a variety of perspectives on a topic.

Don’t assume that you can’t find a book relevant to a topic that is fairly recent, since books may be published within a year of a major event.

Source: Photo courtesy of Lin Kristensen, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Books_of_the_Past.jpg.

To evaluate the credibility of a book, you’ll want to know some things about the author. You can usually find this information at the front or back of the book. If an author is a credentialed and recognized expert in his or her area, the book will be more credible. But just because someone wrote a book on a subject doesn’t mean he or she is the most credible source. For example, a quick search online brings up many books related to public speaking that are written by people who have no formal training in communication or speech. While they may have public speaking experience that can help them get a book deal with a certain publisher, that alone wouldn’t qualify them to write a textbook, as textbook authors are expected to be credentialed experts—that is, people with experience and advanced training/degrees in their area. The publisher of a book can also be an indicator of credibility. Books published by university/academic presses (University of Chicago Press, Duke University Press) are considered more credible than books published by trade presses (Penguin, Random House), because they are often peer reviewed and they are not primarily profit driven.

Reference Tools

The transition to college-level research means turning more toward primary sources and away from general reference materials. Primary sourcesMaterials written by people with firsthand experience with an event or researchers/scholars who conducted original research. are written by people with firsthand experiences with an event or researchers/scholars who conducted original research. Unfortunately, many college students are reluctant to give up their reliance on reference tools like dictionaries and encyclopedias. While reference tools like dictionaries and encyclopedias are excellent for providing a speaker with a background on a topic, they should not be the foundation of your research unless they are academic and/or specialized.

Dictionaries are handy tools when we aren’t familiar with a particular word. However, citing a dictionary like Webster’s as a source in your speech is often unnecessary. I tell my students that Webster’s Dictionary is useful when you need to challenge a Scrabble word, but it isn’t the best source for college-level research. You will inevitably come upon a word that you don’t know while doing research. Most good authors define the terms they use within the content of their writing. In that case, it’s better to use the author’s definition than a dictionary definition. Also, citing a dictionary doesn’t show deep research skills; it only shows an understanding of alphabetical order. So ideally you would quote or paraphrase the author’s definition rather than turning to a general dictionary like Webster’s. If you must turn to a dictionary, I recommend an academic dictionary like The Oxford English Dictionary (OED), which is the most comprehensive dictionary in the English language, with more than twenty volumes. You can’t access the OED for free online, but most libraries pay for a subscription that you can access as a student or patron. While the OED is an academic dictionary, it is not specialized, and you may need a specialized dictionary when dealing with very specific or technical terms. The Dictionary of Business and Economics is an example of an academic and specialized dictionary.

Many students have relied on encyclopedias for research in high school, but most encyclopedias, like World Book, Encarta, or Britannica, are not primary sources. Instead, they are examples of secondary sourcesSources that compile and summarize research done by others. that aggregate, or compile, research done by others in a condensed summary. As I noted earlier, reference sources like encyclopedias are excellent resources to get you informed about the basics of a topic, but at the college level, primary sources are expected. Many encyclopedias are Internet based, which makes them convenient, but they are still not primary sources, and their credibility should be even more scrutinized.

Wikipedia’s open format also means it doesn’t generally meet the expectations for credible, scholarly research.

Source: Wikimedia Foundation.

Wikipedia revolutionized how many people retrieve information and pioneered an open-publishing format that allowed a community of people to post, edit, and debate content. While this is an important contribution to society, Wikipedia is not considered a scholarly or credible source. Like other encyclopedias, Wikipedia should not be used in college-level research, because it is not a primary source. In addition, since its content can be posted and edited by anyone, we cannot be sure of the credibility of the content. Even though there are self-appointed “experts” who monitor and edit some of the information on Wikipedia, we cannot verify their credentials or the review process that information goes through before it’s posted. I’m not one of the college professors who completely dismisses Wikipedia, however. Wikipedia can be a great source for personal research, developing news stories, or trivia. Sometimes you can access primary sources through Wikipedia if you review the footnote citations included in an entry. Moving beyond Wikipedia, as with dictionaries, there are some encyclopedias that are better suited for college research. The Encyclopedia of Black America and the Encyclopedia of Disaster Relief are examples of specialized academic reference sources that will often include, in each entry, an author’s name and credentials and more primary source information.

Interviews

When conducting an interview for a speech, you should access a person who has expertise in or direct experience with your speech topic. If you follow the suggestions for choosing a topic that were mentioned earlier, you may already know something about your speech topic and may have connections to people who would be good interview subjects. Previous employers, internship supervisors, teachers, community leaders, or even relatives may be appropriate interviewees, given your topic. If you do not have a connection to someone you can interview, you can often find someone via the Internet who would be willing to answer some questions. Many informative and persuasive speech topics relate to current issues, and most current issues have organizations that represent their needs. For an informative speech on ageism or a persuasive speech on lowering the voting age, a quick Internet search for “youth rights” leads you to the webpage for the National Youth Rights Association. Like most organization web pages, you can click on the “Contact Us” link to get information for leaders in the organization. You could also connect to members of the group through Facebook and interview young people who are active in the organization.

Once you have identified a good interviewee, you will want to begin researching and preparing your questions. Open-ended questions cannot be answered with a “yes” or “no” and can provide descriptions and details that will add to your speech. Quotes and paraphrases from your interview can add a personal side to a topic or at least convey potentially complicated information in a more conversational and interpersonal way.

Even if you record an interview, take some handwritten notes and make regular eye contact with the interviewee to show that you are paying attention.

©Thinkstock

Closed questions can be answered with one or two words and can provide a starting point to get to more detailed information if the interviewer has prepared follow-up questions. Unless the guidelines or occasion for your speech suggest otherwise, you should balance your interview data with the other sources in your speech. Don’t let your references to the interview take over your speech.

Tips for Conducting Interviews

- Do preliminary research to answer basic questions. Many people and organizations have information available publicly. Don’t waste interview time asking questions like “What year did your organization start?” when you can find that on the website.

- Plan questions ahead of time. Even if you know the person, treat it as a formal interview so you can be efficient.

- Ask open-ended questions that can’t be answered with only a yes or no. Questions that begin with how and why are generally more open-ended than do and did questions. Make sure you have follow-up questions ready.

- Use the interview to ask for the personal side of an issue that you may not be able to find in other resources. Personal narratives about experiences can resonate with an audience.

- Make sure you are prepared. If interviewing in person, have paper, pens, and a recording device if you’re using one. Test your recording device ahead of time. If interviewing over the phone, make sure you have good service so you don’t drop the call and that you have enough battery power on your phone. When interviewing on the phone or via video chat, make sure distractions (e.g., barking dogs) are minimized.

- Whether the interview is conducted face-to-face, over the phone, or via video (e.g., Skype), you must get permission to record. Recording can be useful, as it increases accuracy and the level of detail taken away from the interview. Most smartphones have free apps now that allow you to record face-to-face or phone conversations.

- Whether you record or not, take written notes during the interview. Aside from writing the interviewee’s responses, you can also take note of follow-up questions that come to mind or notes on the nonverbal communication of the interviewee.

- Mention ahead of time if you think you’ll have follow-up questions, so the interviewee can expect further contact.

- Reflect and expand on your notes soon after the interview. It’s impossible to transcribe everything during the interview, but you will remember much of what you didn’t have time to write down and can add it in.

- Follow up with a thank-you note. People are busy, and thanking them for their time and the information they provided will be appreciated.

Websites

We already know that utilizing library resources can help you automatically filter out content that may not be scholarly or credible, since the content in research databases is selected and restricted. However, some information may be better retrieved from websites. Even though both research databases and websites are electronic sources, there are two key differences between them that may impact their credibility. First, most of the content in research databases is or was printed but has been converted to digital formats for easier and broader access. In contrast, most of the content on websites has not been printed. Although not always the case, an exception to this is documents in PDF form found on web pages. You may want to do additional research or consult with your instructor to determine if that can count as a printed source. Second, most of the content on research databases has gone through editorial review, which means a professional editor or a peer editor has reviewed the material to make sure it is credible and worthy of publication. Most content on websites is not subjected to the same review process, as just about anyone with Internet access can self-publish information on a personal website, blog, wiki, or social media page. So what sort of information may be better retrieved from websites, and how can we evaluate the credibility of a website?

Most well-known organizations have official websites where they publish information related to their mission. If you know there is an organization related to your topic, you may want to see if they have an official website. It is almost always better to get information from an official website, because it is then more likely to be considered primary source information. Keep in mind, though, that organizations may have a bias or a political agenda that affects the information they put out. If you do get information from an official website, make sure to include that in your verbal citation to help establish your credibility. Official reports are also often best found on websites, as they rarely appear in their full form in periodicals, books, or newspapers. Government agencies, nonprofits, and other public service organizations often compose detailed and credible reports on a wide variety of topics.

The US Census Bureau’s official website is a great place to find current and credible statistics related to population numbers and demographic statistics.

Source: Photo courtesy of U.S. Census Bureau.

A key way to evaluate the credibility of a website is to determine the site’s accountability. By accountability, I mean determining who is ultimately responsible for the content put out and whose interests the content meets. The more information that is included on a website, the better able you will be to determine its accountability. Ideally all or most of the following information would be included: organization/agency name, author’s name and contact information, date the information was posted or published, name and contact information for person in charge of web content (i.e., web editor or webmaster), and a link to information about the organization/agency/business mission. While all this information doesn’t have to be present to warrant the use of the material, the less accountability information is available, the more you should scrutinize the information. You can also begin to judge the credibility of a website by its domain name. Some common domain names are .com, .net, .org, .edu, .mil, and .gov. For each type of domain, there are questions you may ask that will help you evaluate the site’s credibility. You can see a summary of these questions in Table 9.2 "Website Domain Names and Credibility". Note that some domain names are marked as “restricted” and others aren’t. When a domain is restricted, .mil for example, a person or group wanting to register that domain name has to prove that their content is appropriate for the guidelines of the domain name. Essentially, this limits access to the information published on those domain names, which increases the overall credibility.

Table 9.2 Website Domain Names and Credibility

| Domain Name | Purpose | Restricted? | Questions to Ask |

|---|---|---|---|

| .com, .net | Commercial | No | Is the information posted for profit? Is the information posted influenced by advertisers? |

| .org | Mostly noncommercial organizations | No | What is the mission of the organization? Who is responsible for the content? Is the information published to enhance public knowledge or to solicit donations? |

| .edu | Higher education | Yes | Who published the information? (the institution or an administrator, faculty member, staff member, or student) |

| .mil | US military | Yes | Most information on .mil sites will be credible, since it is not published for profit and only limited people have access to post information. |

| .gov | US government | Yes | Most information on .gov sites will be credible, since it is not published for profit and only limited people have access to post information. |

Types of Supporting Material

There are several types of supporting material that you can pull from the sources you find during the research process to add to your speech. They include examples, explanations, statistics, analogies, testimony, and visual aids. You will want to have a balance of information, and you will want to include the material that is most relevant to your audience and is most likely to engage them. When determining relevance, utilize some of the strategies mentioned in Section 9.1 "Selecting and Narrowing a Topic". Thinking about who your audience is and what they know and would like to know will help you tailor your information. Also try to incorporate proxemic informationInformation that is geographically relevant to the audience., meaning information that is geographically relevant to your audience. For example, if delivering a speech about prison reform to an audience made up of Californians, citing statistics from North Carolina prisons would not be as proxemic as citing information from California prisons. The closer you can get the information to the audience, the better. I tell my students to make the information so relevant and proxemic that it is in our backyards, in the car with us on the way to school or work, and in the bed with us while we sleep.

Examples

An exampleA cited case that is representative of a larger whole. is a cited case that is representative of a larger whole. Examples are especially beneficial when presenting information that an audience may not be familiar with. They are also useful for repackaging or reviewing information that has already been presented. Examples can be used in many different ways, so you should let your audience, purpose and thesis, and research materials guide your use. You may pull examples directly from your research materials, making sure to cite the source. The following is an example used in a speech about the negative effects of standardized testing: “Standardized testing makes many students anxious, and even ill. On March 14, 2002, the Sacramento Bee reported that some standardized tests now come with instructions indicating what teachers should do with a test booklet if a student throws up on it.” You may also cite examples from your personal experience, if appropriate: “I remember being sick to my stomach while waiting for my SAT to begin.”

You may also use hypothetical examples, which can be useful when you need to provide an example that is extraordinary or goes beyond most people’s direct experience. Capitalize on this opportunity by incorporating vivid description into the example that appeals to the audience’s senses. Always make sure to indicate when you are using a hypothetical example, as it would be unethical to present an example as real when it is not. Including the word imagine or something similar in the first sentence of the example can easily do this.

Whether real or hypothetical, examples used as supporting material can be brief or extended. Brief examples are usually one or two sentences, as you can see in the following hypothetical example: “Imagine that your child, little sister, or nephew has earned good grades for the past few years of elementary school, loves art class, and also plays on the soccer team. You hear the unmistakable sounds of crying when he or she comes home from school and you find out that art and soccer have been eliminated because students did not meet the federal guidelines for performance on standardized tests.” Brief examples are useful when the audience is already familiar with a concept or during a review. Extended examples, sometimes called illustrations, are several sentences long and can be effective in introductions or conclusions to get the audience’s attention or leave a lasting impression. It is important to think about relevance and time limits when considering using an extended illustration. Since most speeches are given within time constraints, you want to make sure the extended illustration is relevant to your speech purpose and thesis and that it doesn’t take up a disproportionate amount of the speech. If a brief example or series of brief examples would convey the same content and create the same tone as the extended example, I suggest you go with brevity.

Explanations

ExplanationsType of supporting material that clarifies ideas by providing information about what something is, why something is the way it is, or how something works or came to be. clarify ideas by providing information about what something is, why something is the way it is, or how something works or came to be. One of the most common types of explanation is a definition. Definitions do not have to come from the dictionary. Many times, authors will define concepts as they use them in their writing, which is a good alternative to a dictionary definition.

Since quoting a dictionary definition during a speech is difficult, it’s better to put a definition into your own words based on how it is defined in the original source in which it appeared.

©Thinkstock

As you do your research, think about how much your audience likely knows about a given subject. You do not need to provide definitions when information is common knowledge. Anticipate audience confusion and define legal, medical, or other forms of jargon as well as slang and foreign words. Definitions like the following are also useful for words that we are familiar with but may not know specifics: “According to the 2011 book Prohibition: 13 Years That Changed America, what we now know as Prohibition started in 1920 with the passage of the Volstead Act and the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment.” Keep in mind that repeating a definition verbatim from a dictionary often leads to fluency hiccups, because definitions are not written to be read aloud. It’s a good idea to put the definition into your own words (still remembering to cite the original source) to make it easier for you to deliver.

Other explanations focus on the “why” and “how” of a concept. Continuing to inform about Prohibition, a speaker could explain why the movement toward Prohibition began: “The Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution gained support because of the strong political influence of the Anti-Saloon League.” The speaker could go on to explain how the Constitution is amended: “According to the same book, a proposed amendment to the Constitution needs three-fourths of all the states to approve it in order to be ratified.” We use explanations as verbal clarifications to support our claims in daily conversations, perhaps without even noticing it. Consciously incorporating clear explanations into your speech can help you achieve your speech goals.

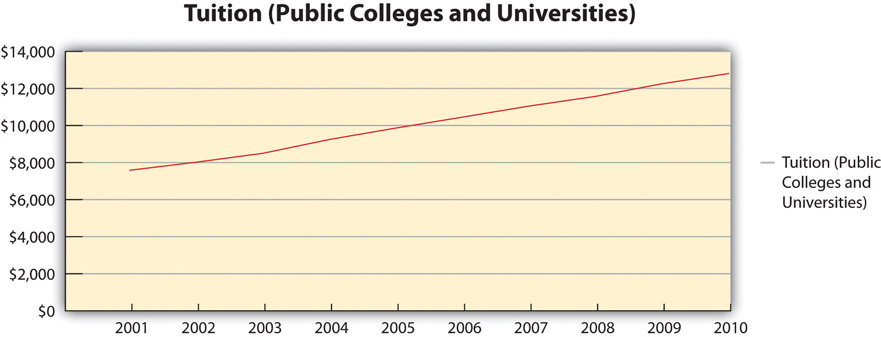

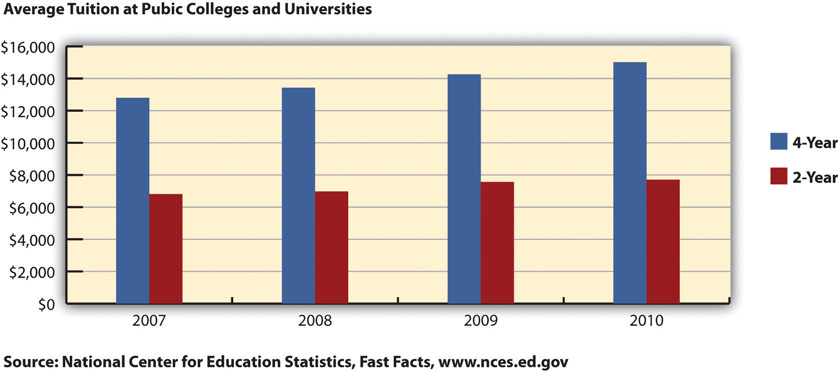

Statistics

StatisticsNumerical representations of information. are numerical representations of information. They are very credible in our society, as evidenced by their frequent use by news agencies, government offices, politicians, and academics. As a speaker, you can capitalize on the power of statistics if you use them appropriately. Unfortunately, statistics are often misused by speakers who intentionally or unintentionally misconstrue the numbers to support their argument without examining the context from which the statistic emerged. All statistics are contextual, so plucking a number out of a news article or a research study and including it in your speech without taking the time to understand the statistic is unethical.

Although statistics are popular as supporting evidence, they can also be boring. There will inevitably be people in your audience who are not good at processing numbers. Even people who are good with numbers have difficulty processing through a series of statistics presented orally. Remember that we have to adapt our information to listeners who don’t have the luxury of pressing a pause or rewind button. For these reasons, it’s a good idea to avoid using too many statistics and to use startling examples when you do use them. Startling statistics should defy our expectations. When you give the audience a large number that they would expect to be smaller, or vice versa, you will be more likely to engage them, as the following example shows: “Did you know that 1.3 billion people in the world do not have access to electricity? That’s about 20 percent of the world’s population according to a 2009 study on the International Energy Agency’s official website.”

You should also repeat key statistics at least once for emphasis. In the previous example, the first time we hear the statistic 1.3 billion, we don’t have any context for the number. Translating that number into a percentage in the next sentence repeats the key statistic, which the audience now has context for, and repackages the information into a percentage, which some people may better understand. You should also round long numbers up or down to make them easier to speak. Make sure that rounding the number doesn’t distort its significance. Rounding 1,298,791,943 to 1.3 billion, for example, makes the statistic more manageable and doesn’t alter the basic meaning. It is also beneficial to translate numbers into something more concrete for visual or experiential learners by saying, for example, “That’s equal to the population of four Unites States of Americas.” While it may seem easy to throw some numbers in your speech to add to your credibility, it takes more work to make them impactful, memorable, and effective.

Tips for Using Statistics

- Make sure you understand the context from which a statistic emerges.

- Don’t overuse statistics.

- Use startling statistics that defy the audience’s expectations.

- Repeat key statistics at least once for emphasis.

- Use a variety of numerical representations (whole numbers, percentages, ratios) to convey information.

- Round long numbers to make them easier to speak.

- Translate numbers into concrete ideas for more impact.

Analogies

AnalogiesType of supporting material that compares ideas, items, or circumstances. involve a comparison of ideas, items, or circumstances. When you compare two things that actually exist, you are using a literal analogy—for example, “Germany and Sweden are both European countries that have had nationalized health care for decades.” Another type of literal comparison is a historical analogy. In Mary Fisher’s now famous 1992 speech to the Republican National Convention, she compared the silence of many US political leaders regarding the HIV/AIDS crisis to that of many European leaders in the years before the Holocaust.

My father has devoted much of his lifetime to guarding against another holocaust. He is part of the generation who heard Pastor Niemöller come out of the Nazi death camps to say, “They came after the Jews and I was not a Jew, so I did not protest. They came after the Trade Unionists, and I was not a Trade Unionist, so I did not protest. They came after the Roman Catholics, and I was not a Roman Catholic, so I did not protest. Then they came after me, and there was no one left to protest.” The lesson history teaches is this: If you believe you are safe, you are at risk.

A figurative analogy compares things that are not normally related, often relying on metaphor, simile, or other figurative language devices. In the following example, wind and revolution are compared: “Just as the wind brings changes in the weather, so does revolution bring change to countries.”

When you compare differences, you are highlighting contrast—for example, “Although the United States is often thought of as the most medically advanced country in the world, other Western countries with nationalized health care have lower infant mortality rates and higher life expectancies.” To use analogies effectively and ethically, you must choose ideas, items, or circumstances to compare that are similar enough to warrant the analogy. The more similar the two things you’re comparing, the stronger your support. If an entire speech on nationalized health care was based on comparing the United States and Sweden, then the analogy isn’t too strong, since Sweden has approximately the same population as the state of North Carolina. Using the analogy without noting this large difference would be misrepresenting your supporting material. You could disclose the discrepancy and use other forms of supporting evidence to show that despite the population difference the two countries are similar in other areas to strengthen your speech.

Testimony

TestimonyQuoted information from people with direct knowledge about a subject or situation. is quoted information from people with direct knowledge about a subject or situation. Expert testimony is from people who are credentialed or recognized experts in a given subject. Lay testimony is often a recounting of a person’s experiences, which is more subjective. Both types of testimony are valuable as supporting material. We can see this in the testimonies of people in courtrooms and other types of hearings. Lawyers know that juries want to hear testimony from experts, eyewitnesses, and friends and family. Congressional hearings are similar.

Congressional hearings often draw on expert and lay testimony to provide a detailed understanding of an event or issue.

Source: Photo courtesy of Federal Emergency Management Agency, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FEMA_-_ 21441_-_Photograph_by_Mark_Wolfe_taken_on_01-14 -2006_in_Mississippi.jpg.

When Toyota cars were malfunctioning and being recalled in 2010, mechanics and engineers were called to testify about the technical specifications of the car (expert testimony), and car drivers like the soccer mom who recounted the brakes on her Prius suddenly failing while she was driving her kids to practice were also called (lay testimony). When using testimony, make sure you indicate whether it is expert or lay by sharing with the audience the context of the quote. Share the credentials of experts (education background, job title, years of experience, etc.) to add to your credibility or give some personal context for the lay testimony (eyewitness, personal knowledge, etc.).

“Getting Competent”

Choosing the Right Supporting Material

As you sift through your research materials to find supporting material to incorporate into your speech, you will want to include a variety of information types. Choosing supporting material that is relevant to your audience will help make your speech more engaging. As was noted earlier, a speaker should consider the audience throughout the speech-making process. Imagine you were asked to deliver a speech about your college or university. To get some practice adapting supporting material to various audiences, provide an example of each type of supporting material that is tailored to the following specific audiences. Include an example, an explanation, a statistic, an analogy, some testimony, and a visual aid.

- Incoming first-year students

- Parents of incoming first-year students

- Alumni of the college or university

- Community members that live close to the school

Visual Aids

Visual aidsMaterials that reinforce speech content visually, which helps amplify the speaker’s message. help a speaker reinforce speech content visually, which helps amplify the speaker’s message. They can be used to present any of the types of supporting materials discussed previously. Speakers rely heavily on an audience’s ability to learn by listening, which may not always be successful if audience members are visual or experiential learners. Even if audience members are good listeners, information overload or external or internal noise can be barriers to a speaker achieving his or her speech goals. Therefore skillfully incorporating visual aids into a speech has many potential benefits:

- Helping your audience remember information because it is presented orally and visually

- Helping your audience understand information because it is made more digestible through diagrams, charts, and so on

- Helping your audience see something in action by demonstrating with an object, showing a video, and so on

- Engaging your audience by making your delivery more dynamic through demonstration, gesturing, and so on

There are several types of visual aids, and each has its strengths in terms of the type of information it lends itself to presenting. The types of visual aids we will discuss are objects; chalkboards, whiteboards, and flip charts; posters and handouts; pictures; diagrams; charts; graphs; videos; and presentation software. It’s important to remember that supporting materials presented on visual aids should be properly cited. We will discuss proper incorporation of supporting materials into a speech in Section 9.3 "Organizing". While visual aids can help bring your supporting material to life, they can also add more opportunities for things to go wrong during your speech. Therefore we’ll discuss some tips for effective creation and delivery as we discuss the various types of visual aids.

Objects

Three-dimensional objects that represent an idea can be useful as a visual aid for a speech. They offer the audience a direct, concrete way to understand what you are saying. I often have my students do an introductory speech where they bring in three objects that represent their past, present, and future. Students have brought in a drawer from a chest that they were small enough to sleep in as a baby, a package of Ramen noodles to represent their life as a college student, and a stethoscope or other object to represent their career goals, among other things. Models also fall into this category, as they are scaled versions of objects that may be too big (the International Space Station) or too small (a molecule) to actually show to your audience.

Tips for Using Objects Effectively

- Make sure your objects are large enough for the audience to see.

- Do not pass objects around, as it will be distracting.

- Hold your objects up long enough for the audience to see them.

- Do not talk to your object, wiggle or wave it around, tap on it, or obstruct the audience’s view of your face with it.

- Practice with your objects so your delivery will be fluent and there won’t be any surprises.

Chalkboards, Whiteboards, and Flip Charts

Chalkboards, whiteboards, and flip charts can be useful for interactive speeches. If you are polling the audience or brainstorming you can write down audience responses easily for everyone to see and for later reference. They can also be helpful for unexpected clarification. If audience members look confused, you can take a moment to expand on a point or concept using the board or flip chart. Since many people are uncomfortable writing on these things due to handwriting or spelling issues, it’s good to anticipate things that you may have to expand on and have prepared extra visual aids or slides that you can include if needed. You can also have audience members write things on boards or flip charts themselves, which helps get them engaged and takes some of the pressure off you as a speaker.

Posters and Handouts

Posters generally include text and graphics and often summarize an entire presentation or select main points. Posters are frequently used to present original research, as they can be broken down into the various steps to show how a process worked. Posters can be useful if you are going to have audience members circulating around the room before or after your presentation, so they can take the time to review the poster and ask questions. Posters are not often good visual aids during a speech, because it’s difficult to make the text and graphics large enough for a room full of people to adequately see. The best posters are those created using computer software and professionally printed on large laminated paper.

Printing/copying businesses are now good at helping produce professional-looking posters. Although they can be costly, they add to the speaker’s credibility.

©Thinkstock

These professional posters come at a price, often costing between forty and sixty dollars. If you opt to make your own poster, take care to make it look professional. Use a computer and printer to print out your text; do not handwrite on a poster. Make sure anything you cut by hand has neat, uniform edges. You can then affix the text, photos, and any accent backing to the poster board. Double-sided tape works well for this, as it doesn’t leave humps like those left by rolled tape or the bubbles, smearing, or sticky mess left by glue.

Handouts can be a useful alternative to posters. Think of them as miniposters that audience members can reference and take with them. Audience members will likely appreciate a handout that is limited to one page, is neatly laid out, and includes the speaker’s contact information. It can be appropriate to give handouts to an audience before a long presentation where note taking is expected, complicated information is presented, or the audience will be tested on or have to respond to the information presented. In most regular speeches less than fifteen minutes long, it would not be wise to distribute handouts ahead of time, as they will distract the audience from the speaker. It’s better to distribute the handouts after your speech or at the end of the program if there are others speaking after you.

Pictures