This is “Explanations and Significance: Developing Your Analysis”, chapter 4 from the book A Guide to Perspective Analysis (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 4 Explanations and Significance: Developing Your Analysis

4.1 Explaining Your Perspective

Learning Objectives

- Introduce Kenneth Burke’s Pentad as a means for focusing on the essential aspects of the subject.

- Discuss how to provide background information for clarification and further analysis.

- Show how a consideration of audience helps to determine which explanations should be included and which ones can remain implied.

- Discuss how to expand explanations through comparison/contrast and personal experience.

To see a world in a grain of sand

And Heaven in a wild flower

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand

And eternity in an hourWilliam Blake, “Auguries of Innocence” The Mentor Book of Major British Poets, ed. Oscar Williams (New York: The New American Library, 1963), 40.

As one of the more mystical poets of the Romantic period, William Blake may have been thinking about the transformative power of the imagination when he wrote these lines, but his words apply equally well to how analysis can open up new perspectives that give greater understanding and appreciation for our subjects. In this chapter, you will learn how to both explain and show the significance of your initial assertions by looking again at the key aspects of the examples that first inspired them. In doing so, your point of view will evolve as your assertions become increasingly clear and complex. Always keep in mind that the more deeply you think about one area of analysis, the more fully you can understand the other areas. To illustrate, let’s take a fresh look at one of the most well known movies of all time.

For those of you who have not seen The Wizard of Oz,Victor Fleming, dir., The Wizard of Oz (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1939). the 1939 film based on the novel by L. Frank Baum, here is a brief synopsis. Dorothy, a young girl from Kansas, is bored with the life that she leads on her uncle and aunt’s farm and spends much of her time dreaming of running away to a magical place “over the rainbow.” Besides her fantasies, she gets most of her happiness from taking care of her dog, Toto, but soon a mean yet influential woman takes the dog away from her and threatens to drown him in a river. Though Toto escapes and returns to Dorothy, Dorothy decides to run away to protect her pet and seek more exciting adventures. She doesn’t get far, however, before she feels guilty for causing her Auntie Em so much worry and returns home, only to get caught in a tornado that takes her, her dog, and her house to the magical land of Oz.

At this point, the movie changes from black and white to color as Dorothy leaves her home to explore these strange new surroundings. Immediately we see that the house has landed on the Wicked Witch of the East, much to the gratitude of the Munchkins, strange little people whom the witch oppresses. Unfortunately for Dorothy, the witch’s sister (the Wicked Witch of the West) is not at all pleased by this and threatens revenge. Before the Wicked Witch of the West can carry this out, however, Glenda, the Good Witch from the North, protects Dorothy by placing the deceased witch’s magical ruby slippers on her feet. Glenda tells Dorothy to follow the Yellow Brick Road to the Emerald City where the Wizard of Oz lives, the only man wise and powerful enough to protect her and help her to return home.

On the way there, Dorothy encounters a scarecrow, a tin man, and a cowardly lion who accompany her on her journey in the hopes that they too will get something from the wizard: a brain, a heart, and courage.

When they finally reach the wizard, he appears as a disembodied head emerging out of fire and speaking with a booming voice of authority. He refuses to help them until they return with the broom of the Wicked Witch of the West, which eventually they do, but on their return they discover that the fiery wizard is merely a projection of a “smoke and mirror” machine. The real wizard, whom Toto finds operating the machine behind a curtain, is an ordinary man with no more power to grant wishes than the rest of them. Nonetheless, he points out to the Scarecrow, the Tin Man and the Lion that they already performed deeds that showed intelligence, compassion, and courage—proving to them that they already possessed the qualities that they thought they lacked. He is not, however, so successful in helping Dorothy, and it seems as though she will never be able to return to Kansas.

Just when all seems lost, Glenda returns and tells Dorothy that she can return home simply by clicking the heals of her slippers together and repeating the phrase: “There’s no place like home.” The resulting magic returns Dorothy to Kansas where she wakes up in her own bed. When she tells her family about her adventure, they believe that it was only a dream brought about by a concussion caused during the storm. Dream or not, Dorothy tells her family that she’s happy to be back and that if she ever feels the urge to look for happiness and fulfillment again, she doesn’t need to look any further than her own backyard.

The Pentad

There are many different ways to analyze this film, but let’s just focus on two common perspectives. Certain feminist analyses have taken issue with how the film might be seen as a warning to women to avoid the dangers of having too much power or straying too far from their “proper” role in the home. Yet others argue the exact opposite and instead see the film as a reminder to trust our own thoughts and feelings over those of questionable authorities. If you tried to explain each of these perspectives by simply summarizing the general plot, your explanation would seem too broad or too obvious. To fully justify your interpretation, you need to look again at the film with a more critical eye, concentrating on those features that validate your main assertions. To determine which details are the most significant and how they relate to each other, I recommend that you use a heuristic (derived from a concept by the social philosopher Kenneth Burke) called “the Pentad”A method of analysis, developed by Kenneth Burke, that helps us to more thoroughly explain a subject by understanding the nature and relationship of its various aspects: act, agent, agency, scene, and purpose.. The Pentad helps you to break apart any scene, whether real or fictional, into five interrelated components that determine its overall shape and direction:

Act: What generally happens.

Agent: Those involved in what happens.

Agency: The means through which it happens.

Scene: When and where it happens.

Purpose: Why it happens.

Of the five areas, the “purpose” is the most difficult to define. It can be understood as the motivation for the actions within the subject itself or it could be stated in terms of what it means to you as spelled out in your working thesis. When defined the second way, the Pentad can help you to explain your thesis more thoroughly by helping you to select the most relevant details and consider how they relate to each other. But, of course, this can happen only after you have taken the time to consider the subject long enough to come up with a working thesis in the first place. To illustrate, consider how the Pentad helps us to look again at The Wizard of Oz in light of the two perspectives mentioned.

If the Purpose is to show how the film may discourage women from leaving the home to pursue careers or take on prominent positions in society, then the way you delineate the other aspects of the Pentad may look like this.

Act: Dorothy’s attempts to leave her home are shown as short lived and irresponsible. She finds satisfaction only at the end of the film when she decides to wander no further than her own backyard, thus preparing her for her inevitable future as a stay-at-home wife and mother.

Agent: Powerful women in both Kansas and Oz are shown as “wicked” and abusive. In contrast, Auntie Em and Glenda are considered “good” because of their feminine and homespun qualities. Glenda knows magic but uses it only in small ways and primarily acts as a nurturing figure.

Agency: Objects of power that fall into women’s hands (the broom, the ruby slippers) are either misunderstood or misused. Dorothy learns to disregard these objects, giving away the broom and using the slippers only to get back to a place where they no longer contain power.

Scene: Though Oz is certainly more “colorful” than Kansas, it’s also shown as more dangerous and unsatisfying, which is why Dorothy chooses to leave it almost as soon as she gets there. At the time the film appeared, women were mostly expected to stay at home and any desire to have a career was often seen as strange or unnatural.

After considering all of these elements, you can then explain your perspective more thoroughly:

For many generations The Wizard of Oz has not only served as entertainment but also as subtle propaganda for rigid gender roles. When the film was released in 1939, few women felt that they could pursue careers outside of the home. Those who wanted to do something else with their lives were often viewed as abnormal or irresponsible. The film clearly reinforces this attitude. Throughout, the women who seek more powerful positions are shown as “wicked” and crazy whereas those who are simply content to look after the home or look pretty are shown as good and stable. Though Dorothy is at first unsatisfied with her role as future homemaker, she eventually decides to embrace it, trading in magical objects like the ruby slippers and witch’s broom for her peaceful yet static rural existence.

This is clearly a valid perspective, one that justifies the main assertion with clear and appropriate examples. But while it brings to light something that should be seriously considered, it is not the only permissible way to see the film. Let’s consider the other perspective that the Purpose of the film might be to encourage a questioning of the traditional family structure along with other beliefs passed down by reason of tradition or authority. As the purpose behind our analysis changes, so do the other corresponding elements of the Pentad:

Act: The characters eventually come to accept their own traits and abilities without any need for external validation. Because the authority figures prove to be unreliable, phony, or just plain wicked, the characters eventually learn to rely on themselves.

Agent: Dorothy’s three companions eventually learn that they don’t need a wizard to grant them the qualities that they already possess. Dorothy too learns to stand up to a witch, to call a wizard a phony, and to eventually tap the power within her that she needs to get back home.

Agency: The wizard uses his “smoke and mirror” device to enhance his authority. Though he tries to create a persona that is “all powerful” and frightening, he is only a little man with no more power or ability to grant wishes than the rest of them.

Scene: Oz is a place for personal enlightenment. And while the film may reflect the cultural attitudes of its time, it may also have inspired future generations to question authority and challenge existing norms.

As before, evaluating these different elements leads to a stronger explanation:

While the characters in the film The Wizard of Oz do not wear buttons stamped with the phrase “Question Authority,” the film as a whole strongly suggests that we do so. Though the characters Dorothy encounters look to the wizard to grant them a brain, a heart, and courage, they already show plenty of intelligence, feeling, and bravery. It’s only after Toto inadvertently exposes the real wizard’s “smoke and mirror” contraption that they see the phony behind the curtain and realize that they don’t need his validation to prove their self-worth. Likewise Dorothy learns to stand up to questionable authorities, and though she chooses to remain in the home, she has helped inspire countless others to say “no” to the rigid roles that restrict them.

Even though these perspectives are very different, each paragraph reveals a reasonable position arising from a close and thoughtful viewing of the film. And perhaps the most useful aspect of the Pentad is that it not only helps you to reexamine the details of your subject in light of your purpose but also to see how the other elements relate to each other. For instance, it helps us to see how exposing the agency of the wizard’s machine inspires the agents to stand up for themselves. As you apply the Pentad, you might also be surprised by how many details you picked up on subconsciously when you arrived at your initial working thesis, justifying your perspective to yourself as well as to others.

Providing Background Information

Doing extra research and providing more background informationExplications about the context from which a subject emerged and clarifications of its more obscure aspects which a writer chooses to include in an essay after evaluating the needs of her audience. can open up even more areas for analysis of The Wizard of Oz. For instance some scholars have argued that the story is based on the political situation at the turn of the Twentieth Century, the time of the novel’s release, and chronicles the rise of the Populist Party, as represented by Dorothy, that attempted to take on the more established Democrat and Republican Parties, as represented by the two wicked witches. You might also want to read interviews with L. Frank Baum, the author, or Victor Fleming, the director, to find out what inspired them to create the book and the movie.

In addition to suggesting new avenues for interpretation, providing background information and research can help you to explain certain aspects of your subjects that might seem unclear because the terms, sounds or images are abstract, dated or specialized. For instance, to explain the quote from The Tempest in the first chapter you might first need to provide modern versions of some of the more archaic terms or reveal how a “baseless fabric” might refer to the painted sets on a stage. Likewise, if you are considering a historical event or a political speech, you should provide information about the surrounding circumstances and the key people involved in the outcome. For instance, to explain why President Bush decided to invade Iraq, you would need to know something about the potential threat Saddam Hussein posed, American economic interests in the Middle East, President Bush’s character and personal motivations, and the general mood of the American public after 9/11.

Considering the Audience

Just how much background you need to provide mostly depends on what you know about the people who will be reading your essay. For instance you will not need to review the basic principles of Sigmund Freud’s theory of id/ego/superego when writing for your psychology professor. But you might want to explain this when writing to your peers. On the other hand, when writing for your professors, you might need to explain references to popular culture that would be unnecessary if you were writing only to your friends. Despite what you may have been taught in the past, you should never assume that your audience doesn’t know anything because you do not want to bore them by explaining obvious references any more than you want to confuse them by withholding important background.

For this reason, you should also take the context of your writing into account before developing your explanations. If, for instance, you were writing an essay for a class about a book that was previously assigned, you would not have to begin with a general synopsis, but could jump straight to the section that corresponds most closely with your assertions. If, however, you were writing to a broader audience, you should first provide them with a general background or a summary of the piece before examining the sections that specifically stood out for you.

Likewise the tone and style of your essay will vary depending on context, audience, and purpose. When writing to a friend on Facebook, you might use vocabulary, abbreviations, and icons that you would never use when writing a more formal essay for your instructor. Even among teachers your tone and style will vary depending on how formal they expect your writing to appear. Teachers, like everyone else, have their own subjective impressions as to what constitutes effective writing. But try not to let this bother you too much because in learning how to communicate effectively to the various audiences you find in school, you will gain a greater rhetorical flexibility to communicate outside of it.

Explaining a Subject Through Comparison and Contrast

Once you provide enough background information for your specific audience, you can further explain your subject through comparison and contrastA method of analysis that helps us to more thoroughly explain a subject by showing how it relates to others, whether actual or hypothetical. with others that relate to it. For instance, to lend validity to the feminist perspective on The Wizard of Oz, you might compare the film to others of the same period that also show powerful women in a negative light. Consider, for instance, how the evil queen in Walt Disney’s 1937 film Snow White and the Seven DwarvesDavid Hand, dir., Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (Walt Disney Productions, 1937). uses her magic to get what she wants, while Snow White, the ideal of femininity, simply waits for a man to come along and rescue her.

You could also underscore how a subject is influenced by cultural attitudes through contrast. For example, if you wanted to explain why a show like South Park or Family Guy has particular appeal to young people today, you might contrast these shows with coming of age television series from other periods. For instance, you could contrast an episode of South Park with an episode of Leave it to Beaver, an iconic series from the 1950s. Though the main characters, Beaver and Wally Cleaver, often get into trouble, it is never anything like the kind that Eric Cartman gets into, and, unlike Cartman, who is spoiled by his single mother, the Cleaver kids are always able to talk out their difficulties with their father who helps them to learn from their mistakes at the end of each episode. Again, the conclusions you draw from this contrast could vary. You might assert that this reveals the necessity of a strong father figure to keep children in check, or you might suggest that the tightly controlled patriarchal family structure of the 1950s inspired rebellion and ridicule in the decades that followed.

Along these lines, you might also consider explaining your subject by contrasting it with how it could have been different by calling our attention to the details that were deliberately omitted. For instance you might analyze an advertisement by revealing what it doesn’t show about the product. Advertisements for fast food restaurants usually show families sitting together, relaxed, and having a good time, but they never show how people usually eat at these places, quickly and alone. And these ads certainly do not reveal the negative effects that eating too much fast food can have on the body, such as heart disease or obesity. Similarly, we can tell a lot about how people feel about something or someone not only by the terms they use but also by the ones they refuse to use. For instance, if the first time you say “I love you” to your significant other only garners the response “thank you,” you might begin to suspect that your feelings run more deeply than those of your partner.

Explaining a Subject Through Personal Values and Experiences

As discussed in the first chapter, the process through which we discover meaning takes place in the interaction between the subject and the viewer/reader/listener. So to fully explain how and why you came up with your assertions, you should also consider how your experiences, your values, even your mood at the moment of encounter can shed light on how you see your subject. As the above examples indicate, you might begin by considering how your surrounding culture influences your response. For instance, Thomas de Zengotita argues that Americans have become so used to media constructions of reality that they often get bored with the real world that is unmitigated by it. To illustrate, he points out that if you were to see wolves in the wild, you might at first be fascinated, but then will quickly lose interest because the sight cannot measure up to the ones that you are used to seeing in movies and on television:

And you will get bored really fast if that ‘wolf’ doesn’t do anything. The kids will start squirming in, like, five minutes; you’ll probably need to pretend you’re not getting bored for a while longer. But if that little smudge of canine out there in the distance continues to just loll around in the tall grass, and you don’t have a really powerful tripod-supported telelens gizmo to play with, you will get bored. You will begin to appreciate how much technology and editing goes into making those nature shows.Thomas de Zengotita, “The Numbing of the American Mind,” Harpers (April 2002), 37.

Other times, your response may emerge from what is going on in your life at the moment of encounter. Consider, for instance, how time and experience might change how we view a subject. When I first heard the song “Time” from Pink Floyd’s album, The Dark Side of the Moon, I came across a line that confused me, “And then one day you find ten years have got behind you /No one told you when to run; you missed the starting gun.” At fifteen, I could not understand how ten years could just get “behind you.” That amount of time was pretty much my entire conscious life. But now at fifty, I understand the line much better. It often seems as though the last ten years have zoomed by, and I have missed “the starting gun” on so many things that I wanted to accomplish.

But we need to be careful here. One reason many teachers do not allow students to use the word “I” is that they often overuse it. If every sentence began with the phrase “I see it this way because” the essay would soon become monotonous and repetitive. Most of the time, you do not need to write this (or similar phrases like “in my opinion”) because it is implied that as the writer you are expressing your point of view. However, like most rules of writing that teachers pass down this one can be taken too far. Often, using “I” will make your writing clearer, more accurate, and more meaningful than constructions that begin with generic subjects like “the reader,” “the viewer” or “one.” These terms can make it tempting to not justify our perspectives, because they can give the impression that all people see a subject in the same way; this simply isn’t true, as evidenced by the fact that we can use these terms to make contradictory assertions: “the reader sees the poem as about the renewal and energy the life force brings to both people and nature”; “the reader views the poem as about the destructive consequences of time.” Think of how much more accurate, meaningful, and clear it is for me to write: “when I was younger I understood the poem to be about the mystery and power that creates life in people and nature, but now (having just turned fifty) I see it as revealing the inevitable decay of both.”

Those teachers who tell their students to never use “I” expect them to seem like objective and indifferent scholars. Yet according to Joan Didion, one of the most prolific and respected essayists of our time, the nature of writing is never like this:

In many ways writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind. It’s an aggressive, even a hostile act. You can disguise its aggressiveness all you want with veils of subordinate clauses and qualifiers and tentative subjunctives, with ellipses and evasions with the whole manner of intimating rather than claiming, of alluding rather than stating but there’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the readers most private space.Joan Didion, “Why I Write” (New York Times Magazine, December 5, 1976).

Michel de Montaigne, the man credited with inventing the essay form, would clearly agree with Didion’s assessment because he frequently used the personal pronoun to acknowledge the subjective nature of his perspectives. Consider this excerpt from “Of Idleness”: “Lately when I returned to my home,…it seemed to me that I could do my mind no greater favor than to let it entertain itself in full idleness and stay and settle in itself, which I hoped it might do more easily now, having become weightier and riper with time.”Michael de Montaigne, “Of Idleness” Montaigne’s Essays and Selected Writing, trans. Donald M Frame (New York: Saint Martin’s Press, 1963), 7. Imagine if he had been expected to write these lines without the use of the personal pronoun: “when one returns to one’s home, it seems to a person….”. So don’t be afraid of including that vertical line when it adds accuracy, clarity, or depth to your explanations.

Whether you choose to explain your subject through background information, cultural influence, personal experience, comparison and contrast with other subjects, or some combination of these, you should never ignore this area of analysis. Your interpretation of a subject may seem apparent to you, but your reader may see it very differently and not understand how you derived your perspectives. By providing explanations, you show that you took the time to pay careful attention. Though not everyone will agree with your point of view, most will at least respect it if they see that you derived your assertions from a close consideration of the subject and did not just rely on a gut reaction based on a brief glance.

Exercise 1

Think of an important event that happened to you, one that you can vividly recall. First consider how the details of it correspond with the Pentad. What generally happened? Which key people were involved? Through what means did it happen? When and where did it happen? And, finally, why did it happen? In answering the last question, you might think of different reasons; for instance, what motivated the actions at the time and what lessons it may have taught you down the road. Now think of how these various aspects relate to each other. For example, if the scene where it took place was unfamiliar to you at the time, how did that shape your response as an agent? Freewrite on these various aspects and on how each relates to the other and then consider how this process gave you a better understanding of both the event and its consequences.

Exercise 2

Look over the event that you just analyzed and write a brief letter about it to two different audiences: to a friend who experienced it with you and to a stodgy older person. Consider the difference in content, how you provide more or less background information to explain what happened and include various considerations as to why and how it happened. Notice, also, the difference in the overall tone, vocabulary and voice. Now think of how you might write the letter to a friend who was not there with you or to a more mellow open-minded older person.

Key Takeaways

- A closer examination of a particular aspect of a subject can lead to a more thorough justification of how we derived our assertions from it.

- Background information can reveal the surface meaning of a subject but should not substitute for a more thorough justification of an interpretation.

- You can explain a subject further by comparing and contrasting it with others (actual or hypothetical), and by relating how your personal beliefs and experiences cause you to see it in a unique light.

- Understanding the needs of the audience who will be reading your essay can help you to determine what additional information you need to provide about both the subject and yourself.

4.2 Considering the Broader Significance

Learning Objectives

- Discuss how to reveal the broader significance of the analysis—personal, cultural, and scholarly.

- Explain how to avoid clichés and broad declarative statements.

- Reveal heuristics that help us explore the significance.

By now you should have a pretty good idea of how to look carefully at your subject, come up with key assertions, find specific examples to illustrate these assertions, and justify your point of view through a close reading. Yet there is still one more area of analysis that we need to discuss: the significance. Sadly, this is the area most often overlooked in school because the answer to the question “Why are you writing the essay?” is so obvious—“Duh, because my teacher told me to.” However, without significance an essay simply becomes an interpretation, which by itself may not mean anything other than an excuse to show off how clever you are. Just as spices give flavor to food, significance is the ingredient that turns an interpretation into a perspective that is meaningful for both the writer and the audience. In fact, outside of school, the primary motivation for engaging in analysis is not to simply show off the ability to discern patterns in a subject, but to call attention to something of wider importance. In exploring the significance, you reveal how the process of analysis engenders new insights about your personal beliefs and experiences as well as the wider cultural concerns that surround both you and your subject.

Whether you choose to explore the personal, cultural, or academic significance of your subject, you will move in the reverse direction from how you derived your explanation. To illustrate, let’s return to The Wizard of Oz for a moment. If I were to use a personal experience to explain how I see one of the key scenes, it might write:

When I was a kid, I always felt intimidated by my teachers. To me they seemed like the fiery machine version of Oz—powerful, untouchable, and all knowing. However, when my mom became friends with my third grade teacher, and I got to know her outside of class, I discovered that she didn’t know everything and had problems just like the rest of us. So when Toto exposes the man behind the curtain, it reminds me of how quickly authority can vanish in the harsh light of reality.

However, to make my analysis significant, I would need to discuss the implications of this further:

You might think that I lost respect for my teacher as I got to see more of her imperfections, but in fact I ended up liking her more, just as I’ve always preferred the humble, human version of Oz to his fiery alter ego. I wish that more authority figures would stop pretending and admit that they don’t know everything. In my experience, people who talk and act with absolute certainty tend to be mediocre teachers and leaders; I have much greater respect for those who aren’t afraid to utter the phrase “I don’t know” once in awhile.

In short, while your explanations justify your perspectives through a discussion of the relevant details contained within your subject, the significance reveals the insights this leads you to discover in other related areas.

Thinking Beyond Clichés and Obvious Classifications

Though there are no hard and fast rules concerning how much you should explore the significance, you should at least take your observations beyond the obvious and cliché. Sometimes clichés don’t make any sense at all; we just repeat them ourselves because we hear others constantly utter them. When I was a child, anytime I would complain that something isn’t fair, my parents would often respond with the cliché “life isn’t fair.” Though I often repeated the phrase myself (especially when I started teaching), I have since decided that it doesn’t really make any sense. “Life” is too big to be broadly characterized as “fair” or “unfair”; instead we all experience countless moments of both justice and injustice. And even if life isn’t fair, that’s no reason for us to act unjustly. We may not have the ability to fix all the seemingly random sufferings that come with living, but we can at least strive to behave in a reasonable manner ourselves.

Other times, clichés become clichés because they are often true, but this does not mean that they are always true for all occasions. In fact, for every cliché you can come up with, you can find another that has the opposite meaning. “Absence can make the heart grow fonder,” but often loved ones who are “out of sight are out of mind.” “Good things may come to those who wait,” but “it’s the early bird that gets the worm.” “The grass may be greener on the other side,” but, as Dorothy reminds us, “there’s no place like home.” And not only can clichés seem contradictory, but also suggest a person’s desire not to think. For instance, if you were having problems with a long distance relationship and asked your roommates for advice, you probably would not want them to simply reply “absence makes the heart grow fonder.” Such a response would imply that they didn’t care enough about you to take into account the specific concerns of your particular situation. Likewise, readers often feel the same way when a cliché substitutes for more detailed significance.

Along with a tendency to overuse clichés, the other factor that prevents writers from thinking very deeply about the implications of their subject occurs when they rely too much on those statements of classification and taste discussed in the previous chapter. When exploring the significance, try not to simply label your subject as “ironic,” or “absurd,” and leave it at that, but also consider why it matters that we see it this way. For instance, you could discuss how certain aspects remind you of an absurdity in your own life that needs correcting. In short, try to move beyond simply showing that you understand the surface meaning of these terms to fully exploring the wider insights that they helped you to discover. If you only rely on a cliché or broad declarative statement, the significance of your essay may disappoint your reader like an unsatisfying punch line to a joke that took forever to set up.

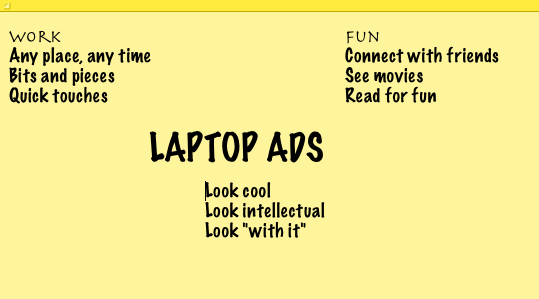

One way to move beyond simple declarative statements or clichés is to brainstorm on what you already know about the significance of your focus. “Brainstorming”A method of exploring the implications of a subject by quickly writing down everything it makes you think of and then organizing the associations into categories. or “listing” is a widely used heuristic in which you quickly write down all the thoughts and associations that you have on a subject to see where the ideas may lead you. To give your mind free reign, you should not pause to censor any of the ideas because sometimes the ones that seem the most bizarre initially can lead to your most profound insights. Consider, for instance, the following brainstorm on the nature and implications of advertisements for laptops:

It’s easy to look like I’m working

Work anywhere I like

Better than carrying a stack of heavy books

Always connected to my friends and fun stuff

Make it my favorite color and it’ll look cool

After doing this for several minutes, you should then look over your jottings to see if any patterns appear. For instance, from my notes above you can see how these commercials might let students think that laptops make it easy for them to look intellectual and do their work in bits and pieces. In addition, this implies that they can use this one product to manage the “lighter side” of their lives—social interactions and relaxation (reading, watching movies).

For those of you who tend to think in concepts before considering the concrete details, you might try clusteringA method of exploring the implications of a subject by first writing down the general categories that relate to it and then listing the specific details that make up these categories. (sometimes referred to as “looping” or “a spider diagram”), a variation of brainstorming in which you move in the opposite direction, from categories to specific instances (and, again, list everything that comes to mind without censorship). In this version, you first write down the main topic you wish to examine in the middle of a piece of paper, surround this topic with the major issues and concerns that come to mind when you think of it, and then surround these issues with the concrete details that they consist of. For instance a cluster around the topic of commercials for laptops might look like this:

Notice that while the layout is different, the considerations appear similar to the ones that emerged while brainstorming. It doesn’t really matter which form you use or how you use it, as long as it sparks new insights.

After taking time out to explore the significance, you can then return to your analysis to integrate your new insights about the broader implications of your piece:

There’s little doubt that laptop advertisements work—or companies wouldn’t continue to use these same tired plots. Typically we see a group of “with it” people— young students at a desk, on the grass or at a coffee shop; well-groomed professionals having success at a business meeting; young children looking at movies or educational learning programs. The laptops may be coordinated to their style or type of clothing (for instance, black or gray for a businessman; red for a college student; pink for a little girl). While people may like what they “see”, the ads don’t necessarily focus on what a laptop really helps you do—preparing work, researching and rewriting presentations or conducting appropriate due diligence on research findings. This same focus on style over substance permeates much of our culture, from politicians who say that they are against government spending while increasing their personal salaries and staff to the students who paste “Go Green” bumper stickers to their unnecessarily large, gas guzzling cars.

The paragraph is much more intriguing than it would be if you tried to sum up the significance too quickly by relying on a cliché: "Buyer Beware." If you think carefully about both the piece and the issues it raises before writing about it more formally, you will develop a much more satisfying discussion of its significance.

The Personal Significance

When looking at the personal significance, it’s helpful to remind yourself that you need to be careful of not overdoing it. A reason that teachers often tell students not to use “I” is that it often encourages them to only talk about themselves and leave the subject behind, leading to the dreaded “tangent” discussed in the first chapter. The temptation to go off course can be very great because it is usually easier to write about yourself than to sustain the close attention a successful analysis requires. For instance, one of my students had a difficult time understanding Woody Allen’s film The Purple Rose of Cairo, so instead of challenging himself to think about it further, he decided to begin his paper this way: “In the film the main character behaves in a manner that is naïve. I too behaved naively once….” And the rest of the paper was about a trip he took to Las Vegas where he lost all the money he needed for college that semester. This might have been fine if he had chosen to write about this experience in the first place; however, he didn’t really analyze what happened to him during the trip either but simply reported on it. Too much attention to the significance leads to tangents, but ignoring it altogether makes the paper seem like a bland academic exercise with no lasting meaning.

Though you might think that it would be easier to discover the personal significance of something that you yourself are involved in, it can often be quite challenging, as anyone who has spent a sleepless night thinking about what a relationship or job means to them can testify. In fact, even something as simple as the trip to the gym that I wrote about in the previous chapter can lead to several complex insights:

So here I am, taking a break from working in front of the computer in order to go to a place where I am surrounded by even more machines, devices to work out on and devices to listen to as I go about it. I sometimes miss being a kid when I hardly relied on technology at all (I grew up before video games, iPods and the Internet). I would go out and play with other kids and we would create our own fantasies, games and exercises. I guess, however, that it is pretty unrealistic to assume that I would have the time to do that now, even if I could find friends my age that would be willing to take a break in the middle of the day. But maybe a change of setting wouldn’t hurt either. Perhaps I can go for a hike tomorrow instead of working out on the elliptical. It may take more time to get to my destination and be less efficient at burning calories, but I’m sure it will be a lot more fun.

None of these insights would have occurred to me if I hadn’t stopped to think about why I felt in such a rut every time I considered working out. I had to challenge myself to think beyond the obvious fact that exercise can sometimes feel like a chore to discover the more specific reasons I felt this way and what I could do to make it better.

The Broader Significance

When looking beyond the personal significance of your subject, you can examine a variety of related topics, depending on what you learned in the course of your analysis. However, the basic question you always need to ask is: how does your analysis offer a more complete and satisfying examination of your subject than those that have been done in the past, and how does this understanding lead to more appropriate insights about the discipline or situation from which your subject emerged? For instance, in his book The Ecology of Fear, environmentalist Mike Davis shows why it is important to reexamine the policies that have guided the city planning of Los Angeles for the past several decades:

For generations, market-driven urbanization has transgressed environmental common sense. Historic wildfire corridors have been turned into view-lot suburbs, wetland liquefactions zones into marinas, and floodplains into industrial districts and housing tracts. Monolithic public works have been substituted for regional planning and a responsible land ethic. As a result, Southern California has reaped flood, fire, and earthquake tragedies that were as avoidable, as unnatural as the beating of Rodney King and the ensuing explosion in the streets. In failing to conserve natural ecosystems it has squandered much of its charm and beauty.Mike Davis, Ecology of Fear (New York: Vintage Books, 1999), 9.

By revealing the disastrous consequences of basing city-planning decisions solely on short-term profits, Davis underscores the importance of his own, environmentally focused, analysis.

For Davis this perspective opens up an entire book outlining how Los Angeles (and by implication other cities) should use ecology, rather than short-term profit as the main guide for how it should develop. But sometimes the significance of your subject will seem so blatantly obvious that it feels like there just isn’t anything left to discuss. This does not necessarily mean that your focus is overly simplistic because many of the most powerful works gravitate toward very definitive points of view. Almost all critics agree that The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain is one of the greatest American novels and yet there is nothing subtle or ambiguous about how it shows slavery as an evil institution, particularly in one key scene. Huck, the narrator, has been helping Jim, a runaway slave, to escape. All his life Huck has been told that slaves are property and that anyone who helps a slave to escape is committing a deadly sin, one that will surely send him to Hell. Finally, Huck’s conscience gets the better of him and he writes a letter to Miss Watson, Jim’s “owner,” alerting her of their location. At first Huck claims, “I felt good and all washed clean of sin for the first time I had ever felt so in my life…” but on further reflection Huck begins to recall all the great things Jim had done for him, how he was the best friend that Huck had ever known, how he was much kinder to Huck than his own father. At that moment Huck sees the letter and makes his decision: “‘All right, then, I’ll go to hell’—and tore it up.”Mark Twain, The Annotated Huckleberry Finn, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn (New York: Norton, 2001), 344. Even if the point is obvious, that Jim is not just property, that slavery is an evil institution, and that Huck’s personal experience is a better guide for his conscience than a warped social morality, the emotional impact of this scene always brings a tear to my eyes.

Yet there are still ways to examine the significance of this scene that take us beyond the obvious: for instance, to discuss how people often distort religious maxims to justify profitable social conventions. Many people who lived at the time the novel takes place argued that slaves were property and The Bible commands us not to steal, and, therefore, helping a slave to escape is breaking one of the Ten Commandments. However, a closer reading of The Bible may lead us to see that the dignity of the individual should matter more than following rules that preserve an unjust social system. After all, Moses, the man who delivered the Ten Commandments in the first place, helped a whole country of slaves to escape. Along these lines we might also consider what issues we currently face that could potentially create conflicts between individual and social morality. Though all reasonable people should now agree that slavery was wrong, we can still speculate as to which actions, behaviors, or beliefs that we embrace today might seem repugnant to future generations.

Of course we can only speculate on future trends, but it isn’t necessary when exploring the significance to come to definitive conclusions. Just as your assertions on a given subject may express ambivalence, so might your discussion of what it implies. It is fine, even desirable, to express ambivalence as long as you do not do so in a vague manner. For example, if you were to consider a current issue that instigates a moral dilemma for you that’s similar to the conflict felt by Huck, you don’t want to simply sound confused: I guess we need to protect the environment, but I don’t know it seems like a hassle sometimes, though I guess I could do more, but I’m really busy right now and the bus is often late, so it’s easier to drive. Instead you might write: If people survive for the next hundred years, they may look back at our generation and shudder about how badly we treated the environment. I wish I could say that I am as dedicated as Huck in defying social convention, but I am just as guilty as most in choosing what is convenient over what is responsible. While the first sentence seems like the jumbled thoughts of one pondering the issue for the first time, the second reads like an intelligent consideration that acknowledges ambivalence.

If you still have trouble articulating what makes your subject significant, I suggest that you go back over the questions for initial consideration raised at the beginning of the last chapter. We are often driven to consider a particular subject because of the meaning it suggests to us, even when we have not yet fully grasped the implications of that meaning. This happens to me all the time. When I go to an art gallery or when I listen to an album, I will focus on a particular painting or song before I realize why it commands my attention. Only later when I’ve had time to really think about it, do I discover that it reminds me of something that happened in the past or helps me to clarify an issue that I’m currently pondering.

Though I’ve broken apart a way to consider analysis into particular elements to discuss each of them more clearly, when we actually begin to write on a subject, it will seldom follow such a neat and linear order. Instead our consideration of these aspects will take place recursively and sometimes in the reverse order of how I presented them, for when we think through the significance, we often come up with more precise assertions, which inspire us to choose more appropriate examples, which we can then explain more thoroughly. This takes time and effort but ultimately what we end up writing will be much more interesting than if we had simply jotted down the first thesis that came to mind and quickly tried to prove it. As we continue to think about our ideas, writing them down, considering them, modifying them, we eventually arrive at perspectives that are clear, reasonable, and worthwhile.

Exercise

Consider a cliché or aphorism that you often heard when you were a child. It could be something that your parents or teachers used to say to motivate you to work or to stop you from complaining. For example, I used to hear “life isn’t fair” to my frequent pointing out of familial injustices. Brainstorm or cluster on ways this cliché has been true in your life and on ways that it has been false or misleading. For example I might first make note of the inevitable injustices that come with living and then list ones that we have the ability to change. Try to fit your ideas into broader categories and then write a paragraph in which you more thoroughly examine the significance suggested by the cliché.

Key Takeaways

- A discussion of the significance of our interpretations can provide greater insight into our selves, our culture, and our core beliefs.

- Broad declarative statements and clichés should be avoided because they do not provide a satisfying exploration of why a particular perspective matters.

- Certain heuristics like brainstorming and clustering can help us to consider the broader implications of our subjects more thoroughly.

- A close examination of one aspect of analysis leads to a better understanding of the other areas as well.