This is “Federalism”, chapter 3 from the book 21st Century American Government and Politics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 3 Federalism

Preamble

The war in Iraq was dragging on long past President George W. Bush’s declaration in May 2003 of the end of formal hostilities. In 2004, the Defense Department, wary of the political pain of reviving the military draft, called up most of the National Guard. The Guard consists of volunteers for state military units headed by the state’s governor but answerable to the commander in chief, the president. Most Guard volunteers expect to serve and keep the peace at home in their states, not fight in a war overseas.

State and local governments made it known that they were being adversely affected by the war. At the 2004 annual meeting of the National Governors Association, governors from both political parties fretted that the call-up had slashed the numbers of the National Guard available for states’ needs by as much as 60 percent. Their concerns made the front page of the New York Times. The story began, “Many of the nation’s governors complained…that they were facing severe manpower shortages in guarding prisoners, fighting wildfires, preparing for hurricanes and floods and policing the streets.”Sarah Kershaw, “Governors Tell of War’s Impact on Local Needs,” New York Times, July 20, 2004, A1.

Governors mingling-speaking at the National Governors Association. The annual meeting of the National Governors Association provides an opportunity for state officials to meet with each other, with national officials, and with reporters.

This involvement of state governors in foreign policy illustrates the complexity of American federalism. The national government has an impact on state and local governments, which in turn influence each other and the national government.

The story also shows how the news media’s depictions can connect and affect different levels of government within the United States. The governors meet each year to exchange ideas and express common concerns. These meetings give them an opportunity to try to use the news media to bring public attention to their concerns, lobby the national government, and reap policy benefits for their states.

But the coverage the governors received in the Iraq case was exceptional. The news media seldom communicate the dynamic complexity of government across national, state, and local levels. Online media are better at enabling people to negotiate the bewildering thicket of the federal system and communicate between levels of government.

FederalismThe allocation of powers and responsibilities among national, state, and local governments and the intergovernmental relations between them. is the allocation of powers and responsibilities among national, state, and local governments and the intergovernmental relations between them. The essence of federalism is that “all levels of government in the United States significantly participate in all activities of government.”See Morton Grodzins’s classic book The American System: A New View of Government in the United States (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1966), 13. At the same time, each level of government is partially autonomous from the rest.We follow the founders who reserved “national government” for the legislative, presidential, and judicial branches at the national level, saving “federal government” for the entity consisting of national, state, and local levels. See Paul E. Peterson, The Price of Federalism (Washington, DC: Brookings, 1995), 13–14.

3.1 Federalism as a Structure for Power

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What is federalism?

- What powers does the Constitution grant to the national government?

- What powers does the Constitution grant to state governments?

The Constitution and its amendments outline distinct powers and tasks for national and state governments. Some of these constitutional provisions enhance the power of the national government; others boost the power of the states. Checks and balances protect each level of government against encroachment by the others.

National Powers

The Constitution gives the national government three types of power. In particular, Article I authorizes Congress to act in certain enumerated domains.

Exclusive Powers

The Constitution gives exclusive powersPowers that the Constitution grants to the national or state governments and prevents the other level from exercising. to the national government that states may not exercise. These are foreign relations, the military, war and peace, trade across national and state borders, and the monetary system. States may not make treaties with other countries or with other states, issue money, levy duties on imports or exports, maintain a standing army or navy, or make war.

Concurrent Powers

The Constitution accords some powers to the national government without barring them from the states. These concurrent powersPowers that the Constitution specifies that either national or state governments may exercise. include regulating elections, taxing and borrowing money, and establishing courts.

National and state governments both regulate commercial activity. In its commerce clauseThe section in the Constitution that gives Congress the power to “regulate Commerce with foreign nations, and among the several States and with the Indian tribes.”, the Constitution gives the national government broad power to “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States and with the Indian tribes.” This clause allowed the federal government to establish a national highway system that traverses the states. A state may regulate any and all commerce that is entirely within its borders.

National and state governments alike make and enforce laws and choose their own leaders. They have their own constitutions and court systems. A state’s Supreme Court decision may be appealed to the US Supreme Court provided that it raises a “federal question,” such as an interpretation of the US Constitution or of national law.

Implied Powers

The Constitution authorizes Congress to enact all laws “necessary and proper” to execute its enumerated powers. This necessary and proper clauseConstitutional provision that gives Congress vast power to enact all laws it considers “necessary and proper” to carry out its enumerated powers. allows the national government to claim implied powersUnlisted powers to the national government that are logical extensions from powers expressly enumerated in the Constitution., logical extensions of the powers explicitly granted to it. For example, national laws can and do outlaw discrimination in employment under Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce.

States’ Powers

The states existed before the Constitution, so the founders said little about their powers until the Tenth Amendment was added in 1791. It holds that “powers not delegated to the United States…nor prohibited by it [the Constitution] to the States, are reserved to the States…or to the people.” States maintain inherent powers that do not conflict with the Constitution. Notably, in the mid-nineteenth century, the Supreme Court recognized that states could exercise police powersInherent powers that states hold to protect the public’s health, safety, order, and morals. to protect the public’s health, safety, order, and morals.License Cases, 5 How. 504 (1847).

Reserved Powers

Some powers are reserved to the states, such as ratifying proposed amendments to the Constitution and deciding how to elect Congress and the president. National officials are chosen by state elections.

Congressional districts are drawn within states. Their boundaries are reset by state officials after the decennial census. So the party that controls a state’s legislature and governorship is able to manipulate districts in its favor. Republicans, having taken over many state governments in the 2010 elections, benefited from this opportunity.

National Government’s Responsibilities to the States

The Constitution lists responsibilities the national government has to the states. The Constitution cannot be amended to deny the equal representation of each state in the Senate. A state’s borders cannot be altered without its consent. The national government must guarantee each state “a republican form of government” and defend any state, upon its request, from invasion or domestic upheaval.

States’ Responsibilities to Each Other

Article IV lists responsibilities states have to each other: each state must give “full faith and credit” to acts of other states. For instance, a driver’s license issued by one state must be recognized as legal and binding by another.

No state may deny “privileges and immunities” to citizens of other states by refusing their fundamental rights. States can, however, deny benefits to out-of-staters if they do not involve fundamental rights. Courts have held that a state may require newly arrived residents to live in the state for a year before being eligible for in-state (thus lower) tuition for public universities, but may not force them to wait as long before being able to vote or receive medical care.

Officials of one state must extradite persons upon request to another state where they are suspected of a crime.

States dispute whether and how to meet these responsibilities. Conflicts sometimes are resolved by national authority. In 2003, several states wanted to try John Muhammad, accused of being the sniper who killed people in and around Washington, DC. The US attorney general, John Ashcroft, had to decide which jurisdiction would be first to put him on trial. Ashcroft, a proponent of capital punishment, chose the state with the toughest death-penalty law, Virginia.

“The Supreme Law of the Land” and Its Limits

Article VI’s supremacy clauseThe section in the Constitution that specifies that the Constitution and all national laws are “the supreme law of the land” and supersede any conflicting state or local laws. holds that the Constitution and all national laws are “the supreme law of the land.” State judges and officials pledge to abide by the US Constitution. In any clash between national laws and state laws, the latter must give way. However, as we shall see, boundaries are fuzzy between the powers national and state governments may and may not wield. Implied powers of the national government, and those reserved to the states by the Tenth Amendment, are unclear and contested. The Constitution leaves much about the relative powers of national and state governments to be shaped by day-to-day politics in which both levels have a strong voice.

A Land of Many Governments

“Disliking government, Americans nonetheless seem to like governments, for they have so many of them.”Martha Derthick, Keeping the Compound Republic: Essays on American Federalism (Washington, DC: Brookings, 2001), 83. Table 3.1 "Governments in the United States" catalogs the 87,576 distinct governments in the fifty states. They employ over eighteen million full-time workers. These numbers would be higher if we included territories, Native American reservations, and private substitutes for local governments such as gated developments’ community associations.

Table 3.1 Governments in the United States

| National government | 1 |

| States | 50 |

| Counties | 3,034 |

| Townships | 16,504 |

| Municipalities | 19,429 |

| Special districts | 35,052 |

| Independent school districts | 13,506 |

| Total governmental units in the United States | 87,576 |

Source: US Bureau of the Census, categorizing those entities that are organized, usually chosen by election, with a governmental character and substantial autonomy.

States

In one sense, all fifty states are equal: each has two votes in the US Senate. The states also have similar governmental structures to the national government: three branches—executive, legislative, and judicial (only Nebraska has a one chamber—unicameral—legislature). Otherwise, the states differ from each other in numerous ways. These include size, diversity of inhabitants, economic development, and levels of education. Differences in population are politically important as they are the basis of each state’s number of seats in the House of Representatives, over and above the minimum of one seat per state.

States get less attention in the news than national and local governments. Many state events interest national news organizations only if they reflect national trends, such as a story about states passing laws regulating or restricting abortions.John Leland, “Abortion Foes Advance Cause at State Level,” New York Times, June 3, 2010, A1, 16.

A study of Philadelphia local television news in the early 1990s found that only 10 percent of the news time concerned state occurrences, well behind the 18 percent accorded to suburbs, 21 percent to the region, and 37 percent to the central city.Phyllis Kaniss, Making Local News (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), table 4.4. Since then, the commitment of local news outlets to state news has waned further. A survey of state capitol news coverage in 2002 revealed that thirty-one state capitols had fewer newspaper reporters than in 2000.Charles Layton and Jennifer Dorroh, “Sad State,” American Journalism Review, June 2002, http://www.ajr.org/article_printable.asp?id=2562.

Native American Reservations

In principle, Native American tribes enjoy more independence than states but less than foreign countries. Yet the Supreme Court, in 1831, rejected the Cherokee tribe’s claim that it had the right as a foreign country to sue the state of Georgia. The justices said that the tribe was a “domestic dependent nation.”Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 US 1 (1831). As wards of the national government, the Cherokee were forcibly removed from land east of the Mississippi in ensuing years.

Native Americans have slowly gained self-government. Starting in the 1850s, presidents’ executive orders set aside public lands for reservations directly administered by the national Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). During World War II, Native Americans working for the BIA organized to gain legal autonomy for tribes. Buttressed by Supreme Court decisions recognizing tribal rights, national policy now encourages Native American nations on reservations to draft constitutions and elect governments.See Charles F. Wilkinson, American Indians, Time, and the Law: Native Societies in a Modern Constitutional Democracy (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987); George Pierre Castile, To Show Heart: Native American Self-Determination and Federal Indian Policy, 1960–1975 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1998); and Kenneth R. Philp, Termination Revisited: American Indians on the Trail to Self-Determination, 1933–1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999).

Figure 3.1 Foxwoods Advertisement

The image of glamour and prosperity at casinos operated at American Indian reservations, such as Foxwoods (the largest such casino) in Connecticut, is a stark contrast with the hard life and poverty of most reservations.

© Thinkstock

Since the Constitution gives Congress and the national government exclusive “power to regulate commerce…with the Indian tribes,” states have no automatic authority over tribe members on reservations within state borders.Worcester v. Georgia, 31 US 515 (1832). As a result, many Native American tribes have built profitable casinos on reservations within states that otherwise restrict most gambling.Montana v. Blackfeet Tribe of Indians, 471 US 759 (1985); California v. Cabazon Band of Indians, 480 US 202 (1987); Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida, 517 US 44 (1996).

Local Governments

All but two states are divided into administrative units known as counties.The two exceptions are Alaska, which has boroughs that do not cover the entire area of the state, and Louisiana, where the equivalents of counties are parishes. States also contain municipalities, whether huge cities or tiny hamlets. They differ from counties by being established by local residents, but their powers are determined by the state. Cutting across these borders are thousands of school districts as well as special districts for drainage and flood control, soil and water conservation, libraries, parks and recreation, housing and community development, sewerage, water supply, cemeteries, and fire protection.The US Bureau of the Census categorizes those entities that are organized (usually chosen by election) with a governmental character and substantial autonomy. US Census Bureau, Government Organization: 2002 Census of Governments 1, no. 1: 6, http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/gc021x1.pdf.

Key Takeaways

Federalism is the American political system’s arrangement of powers and responsibilities among—and ensuing relations between—national, state, and local governments. The US Constitution specifies exclusive and concurrent powers for the national and state governments. Other powers are implied and determined by day-to-day politics.

Exercises

- Consider the different powers that the Constitution grants exclusively to the national government. Explain why it might make sense to reserve each of those powers for the national government.

- Consider the different powers that the Constitution grants exclusively to the states. Explain why it might make sense to reserve each of those powers to the states.

- In your opinion, what is the value of the “necessary and proper” clause? Why might it be difficult to enumerate all the powers of the national government in advance?

3.2 The Meanings of Federalism

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How has the meaning of federalism changed over time?

- Why has the meaning of federalism changed over time?

- What are states’ rights and dual, cooperative, and competitive federalism?

The meaning of federalism has changed over time. During the first decades of the republic, many politicians held that states’ rightsAn approach to federalism that holds that each state entered into a compact in ratifying the Constitution and can therefore decide whether or not to obey a law it considers unconstitutional. allowed states to disobey any national government that in their view exceeded its powers. Such a doctrine was largely discredited after the Civil War. Then dual federalismAn approach to federalism that divides power between national and state governments into distinct, clearly demarcated domains of authority., a clear division of labor between national and state government, became the dominant doctrine. During the New Deal of the 1930s, cooperative federalismAn approach to federalism that sees national, state, and local governments working together to address problems and implement public policies in numerous domains., whereby federal and state governments work together to solve problems, emerged and held sway until the 1960s. Since then, the situation is summarized by the term competitive federalismAn approach to federalism that stresses the conflict and compromise between national, state, and local governments., whereby responsibilities are assigned based on whether the national government or the state is thought to be best able to handle the task.

States’ Rights

The ink had barely dried on the Constitution when disputes arose over federalism. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton hoped to build a strong national economic system; Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson favored a limited national government. Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian factions in President George Washington’s cabinet led to the first political parties: respectively, the Federalists, who favored national supremacy, and the Republicans, who supported states’ rights.

Compact Theory

In 1798, Federalists passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, outlawing malicious criticism of the government and authorizing the president to deport enemy aliens. In response, the Republican Jefferson drafted a resolution passed by Kentucky’s legislature, the first states’ rights manifesto. It set forth a compact theory, claiming that states had voluntarily entered into a “compact” to ratify the Constitution. Consequently, each state could engage in “nullification” and “judge for itself” if an act was constitutional and refuse to enforce it.Forrest McDonald, States’ Rights and the Union: Imperium in Imperio, 1776–1876 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2000), 38–43. However, Jefferson shelved states’ rights when, as president, he directed the national government to purchase the enormous Louisiana Territory from France in 1803.

Links

Alien and Sedition Acts

Read more about the Alien and Sedition Acts online at http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/Alien.html.

Jefferson’s Role

Read more about Jefferson’s role online at http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jefffed.html.

Slavery and the Crisis of Federalism

After the Revolutionary War, slavery waned in the North, where slaves were domestic servants or lone farmhands. In the South, labor-intensive crops on plantations were the basis of Southern prosperity, which relied heavily on slaves.This section draws on James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988).

In 1850, Congress faced the prospect of new states carved from land captured in the Mexican War and debated whether they would be slave or free states. In a compromise, Congress admitted California as a free state but directed the national government to capture and return escaped slaves, even in free states. Officials in Northern states decried such an exertion of national power favoring the South. They passed state laws outlining rights for accused fugitive slaves and forbidding state officials from capturing fugitives.Thomas D. Morris, Free Men All: The Personal Liberty Laws of the North, 1780–1861 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974). The Underground Railroad transporting escaped slaves northward grew. The saga of hunted fugitives was at the heart of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which sold more copies proportional to the American population than any book before or since.

Figure 3.2 Lithograph from Uncle Tom’s Cabin

The plight of fugitive slaves, vividly portrayed in the mega best seller of the 1850s, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, created a crisis in federalism that led directly to the Civil War.

In 1857, the Supreme Court stepped into the fray. Dred Scott, the slave of a deceased Missouri army surgeon, sued for freedom, noting he had accompanied his master for extended stays in a free state and a free territory.An encyclopedic account of this case is Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978). The justices dismissed Scott’s claim. They stated that blacks, excluded from the Constitution, could never be US citizens and could not sue in federal court. They added that any national restriction on slavery in territories violated the Fifth Amendment, which bars the government from taking property without due process of law. To many Northerners, the Dred Scott decision raised doubts about whether any state could effectively ban slavery. In December 1860, a convention in South Carolina repealed the state’s ratification of the Constitution and dissolved its union with the other states. Ten other states followed suit. The eleven formed the Confederate States of America (see Note 3.19 "Enduring Image").

Links

The Underground Railroad

Learn more about the Underground Railroad online at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p2944.html.

The Dred Scott Case

Learn more about the Dred Scott case from the Library of Congress at http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/DredScott.html.

Enduring Image

The Confederate Battle Flag

The American flag is an enduring image of the United States’ national unity. The Civil War battle flag of the Confederate States of America is also an enduring image, but of states’ rights, of opposition to a national government, and of support for slavery. The blue cross studded with eleven stars for the states of the Confederacy was not its official flag. Soldiers hastily pressed it into battle to avoid confusion between the Union’s Stars and Stripes and the Confederacy’s Stars and Bars. After the South’s defeat, the battle flag, often lowered for mourning, was mainly a memento of gallant human loss.See especially Robert E. Bonner, Colors and Blood: Flag Passions of the Confederate South (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002).

The flag’s meaning was transformed in the 1940s as the civil rights movement made gains against segregation in the South. One after another Southern state flew the flag above its capitol or defiantly redesigned the state flag to incorporate it. Over the last sixty years, a myriad of meanings arousing deep emotions have become attached to the flag: states’ rights; Southern regional pride; a general defiance of big government; nostalgia for a bygone era; racist support of segregation; or “equal rights for whites.”For overviews of these meanings see Tony Horwitz, Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War (New York: Random House, 1998) and J. Michael Martinez, William D. Richardson, and Ron McNinch-Su, eds., Confederate Symbols in the Contemporary South (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2000).

Confederate Flag

© Thinkstock

The battle flag appeals to politicians seeking resonant images. But its multiple meanings can backfire. In 2003, former Vermont governor Howard Dean, a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination, addressed the Democratic National Committee and said, “White folks in the South who drive pickup trucks with Confederate flag decals on the back ought to be voting with us, and not them [Republicans], because their kids don’t have health insurance either, and their kids need better schools too.” Dean received a rousing ovation, so he probably thought little of it when he told the Des Moines Register, “I still want to be the candidate for guys with Confederate flags in their pickup trucks.”All quotes come from “Dems Battle over Confederate Flag,” CNN, November 2, 2003, http://www.cnn.com/2003/ALLPOLITICS/11/01/elec04.prez.dean.confederate.flag. Dean, the Democratic front runner, was condemned by his rivals who questioned his patriotism, judgment, and racial sensitivity. Dean apologized for his remark.“Dean: ‘I Apologize’ for Flag Remark,” CNN, November 7, 2003, http://www.cnn.com/2003/ALLPOLITICS/11/06/elec04.prez.dean.flag.

The South’s defeat in the Civil War discredited compact theory and nullification. Since then, state officials’ efforts to defy national orders have been futile. In 1963, Governor George Wallace stood in the doorway of the University of Alabama to resist a court order to desegregate the all-white school. Eventually, he had no choice but to accede to federal marshals. In 1994, Pennsylvania governor Robert Casey, a pro-life Democrat, decreed he would not allow state officials to enforce a national order that state-run Medicaid programs pay for abortions in cases of rape and incest. He lost in court.David L. Shapiro, Federalism: A Dialogue (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1995), 98 n. 139.

Dual Federalism

After the Civil War, the justices of the Supreme Court wrote, “The Constitution, in all its provisions, looks to an indestructible Union, composed of indestructible States.”Texas v. White, 7 Wall. 700 (1869). They endorsed dual federalism, a doctrine whereby national and state governments have clearly demarcated domains of power. The national government is supreme, but only in the areas where the Constitution authorizes it to act.

The basis for dual federalism was a series of Supreme Court decisions early in the nineteenth century. The key decision was McCulloch v. Maryland (1819). The Court struck down a Maryland state tax on the Bank of the United States chartered by Congress. Chief Justice Marshall conceded that the Constitution gave Congress no explicit power to charter a national bank,McCulloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316 (1819). but concluded that the Constitution’s necessary-and-proper clause enabled Congress and the national government to do whatever it deemed “convenient or useful” to exercise its powers. As for Maryland’s tax, he wrote, “the power to tax involves the power to destroy.” Therefore, when a state’s laws interfere with the national government’s operation, the latter takes precedence. From the 1780s to the Great Depression of the 1930s, the size and reach of the national government were relatively limited. As late as 1932, local government raised and spent more than the national government or the states.

Link

McCulloch v. Maryland

Read more about McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) online at http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/antebellum/landmark_mcculloch.html.

On two subjects, however, the national government increased its power in relationship to the states and local governments: sin and economic regulation.

The Politics of Sin

National powers were expanded when Congress targeted obscenity, prostitution, and alcohol.This section draws on James A. Morone, Hellfire Nation: The Politics of Sin in American History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), chaps. 8–11. In 1872, reformers led by Anthony Comstock persuaded Congress to pass laws blocking obscene material from being carried in the US mail. Comstock had a broad notion of sinful media: all writings about sex, birth control, abortion, and childbearing, plus tabloid newspapers that allegedly corrupted innocent youth.

Figure 3.3

The first book by Anthony Comstock, who headed the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, aimed at the supposedly corrupting influence of the tabloid media of the day on children and proposed increasing the power of the national government to combat them.

Source: Morone, James A., Hellfire Nation: The Politics of Sin in American History, (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), 233.

As a result of these laws, the national government gained the power to exclude material from the mail even if it was legal in individual states.

The power of the national government also increased when prostitution became a focus of national policy. A 1910 exposé in McClure’s magazine roused President William Howard Taft to warn Congress about prostitution rings operating across state lines. The ensuing media frenzy depicted young white girls torn from rural homes and degraded by an urban “white slave trade.” Using the commerce clause, Congress passed the Mann Act to prohibit the transportation “in interstate commerce…of any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.”Quoted in James A. Morone, Hellfire Nation: The Politics of Sin in American History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), 266. The bill turned enforcement over to a tiny agency concerned with antitrust and postal violations, the Bureau of Investigations. The Bureau aggressively investigated thousands of allegations of “immoral purpose,” including unmarried couples crossing state lines to wed and interracial married couples.

The crusade to outlaw alcohol provided the most lasting expansion of national power. Reformers persuaded Congress in 1917 to bar importation of alcohol into dry states, and, in 1919, to amend the Constitution to allow for the nationwide prohibition of alcohol. Pervasive attempts to evade the law boosted organized crime, a rationale for the Bureau of Investigations to bloom into the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the equivalent of a national police force, in the 1920s.

Prohibition was repealed in 1933. But the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover, its director from the 1920s to the 1970s, continued to call attention through news and entertainment media to the scourge of organized crime that justified its growth, political independence, and Hoover’s power. The FBI supervised film depictions of the lives of criminals like John Dillinger and long-running radio and television shows like The FBI. The heroic image of federal law enforcement would not be challenged until the 1960s when the classic film Bonnie and Clyde romanticized the tale of two small-time criminals into a saga of rebellious outsiders crushed by the ominous rise of authority across state lines.

Economic Regulation

Other national reforms in the late nineteenth century that increased the power of the national government were generated by reactions to industrialization, immigration, and urban growth. Crusading journalists decried the power of big business. Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle exposed miserable, unsafe working conditions in America’s factories. These reformers feared that states lacked the power or were reluctant to regulate railroads, inspect meat, or guarantee food and drug safety. They prompted Congress to use its powers under the commerce clause for economic regulation, starting with the Interstate Commerce Act in 1887 to regulate railroads and the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890 to outlaw monopolies.

The Supreme Court, defending dual federalism, limited such regulation. It held in 1895 that the national government could only regulate matters directly affecting interstate commerce.United States v. E. C. Knight, 156 US 1 (1895). In 1918, it ruled that Congress could not use the commerce clause to deal with local matters like conditions of work. The national government could regulate interstate commerce of harmful products such as lottery tickets or impure food.Hammer v. Dagenhart, 247 US 251 (1918). A similar logic prevented the US government from using taxation powers to the same end. Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Company, 259 US 20 (1922).

Cooperative Federalism

The massive economic crises of the Great Depression tolled the death knell for dual federalism. In its place, cooperative federalism emerged. Instead of a relatively clear separation of policy domains, national, state, and local governments would work together to try to respond to a wide range of problems.

The New Deal and the End of Dual Federalism

Elected in 1932, Democratic president Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) sought to implement a “New Deal” for Americans amid staggering unemployment. He argued that the national government could restore the economy more effectively than states or localities. He persuaded Congress to enact sweeping legislation. New Deal programs included boards enforcing wage and price guarantees; programs to construct buildings and bridges, develop national parks, and create artworks; and payments to farmers to reduce acreage of crops and stabilize prices.

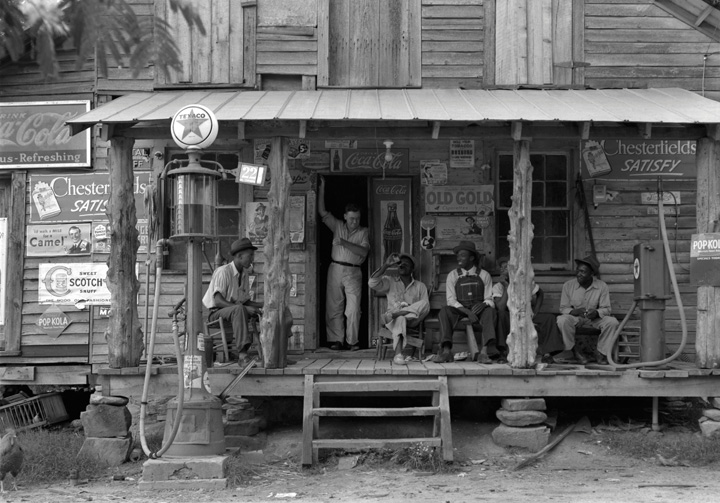

Figure 3.4 Dorothea Lange Photograph

The 1930s New Deal programs included commissioning photographers to document social conditions during the Great Depression. The resultant photographs are both invaluable historical documents and lasting works of art.

Source: Photo courtesy of the US Farm Security Administration, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dorothea_Lange,_Country_store_on_dirt _road,_Gordonton,_North_Carolina,_1939.jpg.

By 1939, national government expenditures equaled state and local expenditures combined.Thomas Anton, American Federalism & Public Policy: How the System Works (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1988), 41. FDR explained his programs to nationwide audiences in “fireside chats” on the relatively young medium of radio. His policies were highly popular, and he was reelected by a landslide in 1936. As we describe in Chapter 15 "The Courts", the Supreme Court, after rejecting several New Deal measures, eventually upheld national authority over such once-forbidden terrain as labor-management relations, minimum wages, and subsidies to farmers.Respectively, National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel, 301 US 1 (1937); United States v. Darby, 312 US 100 (1941); Wickard v. Filburn, 317 US 111 (1942). The Court thereby sealed the fate of dual federalism.

Links

The New Deal

Learn more about the New Deal online at http://www.archives.gov/research/alic/reference/new-deal.html.

Fireside Chats

Read the Fireside Chats online at http://docs.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/firesi90.html.

Grants-in-Aid

Cooperative federalism’s central mechanisms were grants-in-aidThe national government’s provision of funds to states or localities to administer particular programs.: the national government passes funds to the states to administer programs. Starting in the 1940s and 1950s, national grants were awarded for infrastructure (airport construction, interstate highways), health (mental health, cancer control, hospital construction), and economic enhancement (agricultural marketing services, fish restoration).David B. Walker, The Rebirth of Federalism: Slouching toward Washington (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 1999), 99.

Grants-in-aid were cooperative in three ways. First, they funded policies that states already oversaw. Second, categorical grantsGrants through which states and localities spend national funds on programs to meet the precise purposes Congress specified. required states to spend the funds for purposes specified by Congress but gave them leeway on how to do so. Third, states’ and localities’ core functions of education and law enforcement had little national government supervision.Martha Derthick, Keeping the Compound Republic: Essays on American Federalism (Washington, DC: Brookings, 2001), 17.

Competitive Federalism

During the 1960s, the national government moved increasingly into areas once reserved to the states. As a result, the essence of federalism today is competition rather than cooperation.Paul E. Peterson, Barry George Rabe, and Kenneth K. Wong, When Federalism Works (Washington, DC: Brookings, 1986), especially chap. 5; Martha Derthick, Keeping the Compound Republic: Essays on American Federalism (Washington, DC: Brookings, 2001), chap. 10.

Judicial Nationalizing

Cooperative federalism was weakened when a series of Supreme Court decisions, starting in the 1950s, caused states to face much closer supervision by national authorities. As we discuss in Chapter 4 "Civil Liberties" and Chapter 5 "Civil Rights", the Court extended requirements of the Bill of Rights and of “equal protection of the law” to the states.

The Great Society

In 1963, President Lyndon Johnson proposed extending the New Deal policies of his hero, FDR. Seeking a “Great Society” and declaring a “War on Poverty,” Johnson inspired Congress to enact massive new programs funded by the national government. Over two hundred new grants programs were enacted during Johnson’s five years in office. They included a Jobs Corps and Head Start, which provided preschool education for poor children.

The Great Society undermined cooperative federalism. The new national policies to help the needy dealt with problems that states and localities had been unable or reluctant to address. Many of them bypassed states to go straight to local governments and nonprofit organizations.David B. Walker, The Rebirth of Federalism: Slouching toward Washington (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 1999), 123–25.

Link

The Great Society

Read more about the Great Society online at http://www.pbs.org/johngardner/chapters/4.html.

Obstacles and Opportunities

In competitive federalism, national, state, and local levels clash, even battle with each other.The term “competitive federalism” is developed in Thomas R. Dye, American Federalism: Competition among Governments (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1990). Overlapping powers and responsibilities create friction, which is compounded by politicians’ desires to get in the news and claim credit for programs responding to public problems.

Competition between levels of federalism is a recurring feature of films and television programs. For instance, in the eternal television drama Law and Order and its offshoots, conflicts between local, state, and national law enforcement generate narrative tension and drama. This media frame does not consistently favor one side or the other. Sometimes, as in the film The Fugitive or stories about civil rights like Mississippi Burning, national law enforcement agencies take over from corrupt local authorities. Elsewhere, as in the action film Die Hard, national law enforcement is less competent than local or state police.

Mandates

Under competitive federalism, funds go from national to state and local governments with many conditions—most notably, directives known as mandatesDirectives from the national government to state and local governments, either as orders or as conditions on the use of national funds..This definition is drawn from Michael Fix and Daphne Kenyon, eds., Coping with Mandates: What Are the Alternatives? (Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press, 1988), 3–4. State and local governments want national funds but resent conditions. They especially dislike “unfunded mandates,” according to which the national government directs them what to do but gives them no funds to do it.

After the Republicans gained control of Congress in the 1994 elections, they passed a rule to bar unfunded mandates. If a member objects to an unfunded mandate, a majority must vote to waive the rule in order to pass it. This reform has had little impact: negative news attention to unfunded mandates is easily displaced by dramatic, personalized issues that cry out for action. For example, in 1996, the story of Megan Kanka, a young New Jersey girl killed by a released sex offender living in her neighborhood, gained huge news attention. The same Congress that outlawed unfunded mandates passed “Megan’s Law”—including an unfunded mandate ordering state and local law enforcement officers to compile lists of sex offenders and send them to a registry run by the national government.

Key Takeaways

Federalism in the United States has changed over time from clear divisions of powers between national, state, and local governments in the early years of the republic to greater intermingling and cooperation as well as conflict and competition today. Causes of these changes include political actions, court decisions, responses to economic problems (e.g., depression), and social concerns (e.g., sin).

Exercises

- What view of federalism allowed the Confederate states to justify seceding from the United States? How might this view make it difficult for the federal government to function in the long run?

- What are the differences between dual federalism and cooperative federalism? What social forces led to the federal state governments working together in a new way?

- How is federalism portrayed in the movies and television shows you’ve seen? Why do you think it is portrayed that way?

3.3 Why Federalism Works (More or Less)

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How do national, state, and local governments interact to make federalism work more or less?

- How are interest groups involved in federalism?

- What are the ideological and political attitudes toward federalism of the Democratic and Republican parties?

When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans and the surrounding areas on August 29, 2005, it exposed federalism’s frailties. The state and local government were overwhelmed, yet there was uncertainty over which level of government should be in charge of rescue attempts. Louisiana governor Kathleen Blanco refused to sign an order turning over the disaster response to federal authorities. She did not want to cede control of the National Guard and did not believe signing the order would hasten the arrival of the troops she had requested. President Bush failed to realize the magnitude of the disaster, then believed that the federal response was effective. In fact, as was obvious to anyone watching television, it was slow and ineffective. New Orleans mayor C. Ray Nagin and state officials accused the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) of failing to deliver urgently needed help and of thwarting other efforts through red tape.

Hurricane Katrina was an exceptional challenge to federalism. Normally, competition between levels of government does not careen out of control, and federalism works, more or less. We have already discussed one reason: a legal hierarchy—in which national law is superior to state law, which in turn dominates local law—dictates who wins in clashes in domains where each may constitutionally act.

There are three other reasons.See also John D. Nugent, Safeguarding Federalism: How States Protect Their Interests in National Policymaking (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009). First, state and local governments provide crucial assistance to the national government. Second, national, state, and local levels have complementary capacities, providing distinct services and resources. Third, the fragmentation of the system is bridged by interest groups, notably the intergovernmental lobby that provides voices for state and local governments. We discuss each reason.

Applying Policies Close to Home

State and local governments are essential parts of federalism because the federal government routinely needs them to execute national policy. State and local governments adjust the policies as best they can to meet their political preferences and their residents’ needs. Policies and the funds expended on them thus vary dramatically from one state to the next, even in national programs such as unemployment benefits.Thomas R. Dye, American Federalism: Competition among Governments (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1990), chap. 2; Paul E. Peterson, The Price of Federalism (Washington, DC: Brookings, 1995), chap. 4.

This division of labor, through which the national government sets goals and states and localities administer policies, makes for incomplete coverage in the news. National news watches the national government, covering more the political games and high-minded intentions of policies then the nitty-gritty of implementation. Local news, stressing the local angle on national news, focuses on the local impact of decisions in distant Washington (see Note 3.29 "Comparing Content").

Comparing Content

Passage of No Child Left Behind Act

The No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act vastly expanded the national government’s supervision of public education with requirements for testing and accountability. Amid the final push toward enacting the law, Washington reporters for national newspapers were caught up in a remarkable story: the bipartisan coalition uniting staunch opponents President George W. Bush and liberal senator Edward Kennedy (D-MA) civilly working together on a bold, historic piece of legislation. Dana Milbank’s Washington Post story was typical. Milbank termed the bill “the broadest rewriting of federal education policy in decades,” and he admired “Washington’s top bipartisan achievement of 2001.”Dana Milbank, “With Fanfare, Bush Signs Education Bill,” Washington Post, January 9, 2002, A3. The looming problems of funding and implementing the act were obscured in the national media’s celebration of the lovefest.

By contrast, local newspapers across the country calculated the benefits and costs of the new legislation on education in their states and localities—in particular, how much money the state would receive under NCLB and whether or not the law’s requirements and deadlines were reasonable. On January 9, 2002, the Boston Globe’s headline was “Mass. Welcomes Fed $$; Will Reap $117M for Schools, Testing,” and the Denver Post noted, “Colorado to Get $500 million for Schools.”Ed Hayward, “Mass. Welcomes Fed $$; Will Reap $117M for Schools, Testing,” Boston Globe, January 9, 2002, 7; Monte Whaley, “Colorado to Get $500 Million for Schools,” Denver Post, January 9, 2002, A6.

Local newspapers sought out comments of state and local education officials and leaders of local teachers’ unions, who were less smitten by the new law. The Sacramento Bee published a lengthy front-page story by reporter Erika Chavez on January 3, shortly before Bush signed the law. Chavez contrasted the bill’s supporters who saw it as “the most meaningful education reform in decades” with opponents who found that “one crucial aspect of the legislation is nothing more than a pipe dream.” Discussing the bill’s provision that all teachers must be fully credentialed in four years, a staffer at the State Department of Education was quoted as saying “The numbers don’t add up, no matter how you look at them.” The California Teachers’ Association’s president called it “fantasy legislation,” adding, “It’s irresponsible to pass this kind of law and not provide the assistance needed to make the goals attainable. I can’t understand the reason or logic that went into this legislation. It’s almost a joke.”Erika Chavez, “Federal Teacher Goal is Blasted; Congress’ Mandate that Instructors Get Credentials in 4 Years is Called Unrealistic,” Sacramento Bee, January 3, 2002, A1.

Complementary Capacities

The second reason federalism often works is because national, state, and local governments specialize in different policy domains.This section draws on Paul E. Peterson, The Price of Federalism (Washington, DC: Brookings, 1995). The main focus of local and state government policy is economic development, broadly defined to include all policies that attract or keep businesses and enhance property values. States have traditionally taken the lead in highways, welfare, health, natural resources, and prisons.Thomas Anton, American Federalism & Public Policy: How the System Works (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1988), table 3.3. Local governments dominate in education, fire protection, sewerage, sanitation, airports, and parking.

The national government is central in policies to serve low-income and other needy persons. In these redistributive policiesPolicies whereby those who pay the taxes usually do not receive the service paid by the taxes., those paying for a service in taxes are not usually those receiving the service.This definition comes from Paul E. Peterson, Barry George Rabe, and Kenneth K. Wong, When Federalism Works (Washington, DC: Brookings, 1986), 15. These programs rarely get positive coverage in the local news, which often shows them as “something-for-nothing” benefits that undeserving individuals receive, not as ways to address national problems.Paul E. Peterson, Barry George Rabe, and Kenneth K. Wong, When Federalism Works (Washington, DC: Brookings, 1986), 19.

States cannot effectively provide redistributive benefits. It is impossible to stop people from moving away because they think they are paying too much in taxes for services. Nor can states with generous benefits stop outsiders from moving there—a key reason why very few states enacted broad health care coverageMark C. Rom and Paul E. Peterson, Welfare Magnets: A New Case for a New National Standard (Washington, DC: Brookings, 1990).—and why President Obama pressed for and obtained a national program. Note, however, that, acknowledging federalism, it is the states’ insurance commissioners who are supposed to interpret and enforce many of the provisions of the new federal health law

The three levels of government also rely on different sources of taxation to fund their activities and policies. The national government depends most heavily on the national income tax, based on people’s ability to pay. This enables it to shift funds away from the wealthier states (e.g., Connecticut, New Jersey, New Hampshire) to poorer states (e.g., New Mexico, North Dakota, West Virginia).

Taxes of local and state governments are more closely connected to services provided. Local governments depend mainly on property taxes, the more valuable the property the more people pay. State governments collect state income taxes but rely most on sales taxes gathered during presumably necessary or pleasurable consumer activity.

Link

Tax and Budget Information for Federal, State, and Local Governments

Find more information about government budgets and taxes.

Federal

http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/federal_govt_finances_employment.html

State

Local

The language of “no new taxes” or “cutting taxes” is an easy slogan for politicians to feature in campaign ads and the news. As a result, governments often increase revenues on the sly, by lotteries, cigarette and alcohol taxes, toll roads, and sales taxes falling mostly on nonresidents (like hotel taxes or surcharges on car rentals).Glenn R. Beamer, Creative Politics: Taxes and Public Goods in a Federal System (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999), chap. 4.

The Intergovernmental Lobby

A third reason federalism often works is because interest groups and professional associations focus simultaneously on a variety of governments at the national, state, and local levels. With multiple points of entry, policy changes can occur in many ways.Thomas Anton, American Federalism & Public Policy: How the System Works (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1988), chap. 5.

In bottom-up change, a problem is first identified and addressed, but not resolved at a local level. People, and often the media, then pressure state and national governments to become involved. Bottom-up change can also take place through an interest group calling on Congress for help.David R. Berman, Local Government and the States: Autonomy, Politics, and Policy (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2003), 20. In 1996, pesticide manufacturers, fed up with different regulations from state to state, successfully pushed Congress to set national standards to make for more uniform, and less rigorous, regulation.

In top-down change, breaking news events inspire simultaneous policy responses at various levels. Huge publicity for the 1991 beating that motorist Rodney King received from Los Angeles police officers propelled police brutality onto the agenda nationwide and inspired many state and local reforms.Regina G. Lawrence, The Politics of Force: Media and the Construction of Police Brutality (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000).

Policy diffusion is a horizontal form of change.Jack L. Walker, “Diffusion of Innovations among American States,” American Political Science Review 63 (1969): 880–99. State and local officials watch what other state and local governments are doing. States can be “laboratories of democracy,” experimenting with innovative programs that spread to other states. They can also make problems worse with ineffective or misdirected policies.

These processes—bottom-up, top-down, and policy diffusion—are reinforced by the intergovernmental lobby. State and local governments lobby the president and Congress. Their officials band together in organizations, such as the National Governors Association, National Association of Counties, the US Conference of Mayors, and the National Conference of State Legislatures. These associations trade information and pass resolutions to express common concerns to the national government. Such meetings are one-stop-shopping occasions for the news media to gauge nationwide trends in state and local government.

Democrats, Republicans, and Federalism

The parties stand for different principles with regard to federalism. Democrats prefer policies to be set by the national government. They opt for national standards for consistency across states and localities, often through attaching stringent conditions to the use of national funds. Republicans decry such centralization and endorse devolution, giving (or, they say, “returning”) powers to the states—and seeking to shrink funds for the national government.

Principled distinctions often evaporate in practice. Both parties have been known to give priority to other principles over federalism and to pursue policy goals regardless of the impact on boundaries between national, state, and local governments.Paul L. Posner, The Politics of Unfunded Mandates: Whither Federalism? (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1998), 223.

So Republicans sometimes champion a national policy while Democrats look to the states. In 2004, the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled that the state could not deny marriage licenses to same-sex couples, and officials in cities like San Francisco defied state laws and began marrying same-sex couples. Led by President George W. Bush, Republicans drafted an amendment to the US Constitution to define marriage as between a man and a woman. Bush charged that “activist judges and local officials in some parts of the country are not letting up in their efforts to redefine marriage for the rest of America.”Carl Hulse, “Senators Block Initiative to Ban Same-Sex Unions,” New York Times, July 15, 2004, A1. Democrats, seeking to defuse the amendment’s appeal, argued that the matter should be left to each of the states. Democrats’ appeal to federalism swayed several Republican senators to vote to kill the amendment.

“The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act,” enacted in February 2009, is another example. This was a dramatic response by Congress and the newly installed Obama administration to the country’s dire economic condition. It included many billions of dollars in a fiscal stabilization fund: aid to the states and localities struggling with record budget deficits and layoffs. Most Democratic members of Congress voted for the legislation even though it gave the funds unconditionally. Republicans opposed the legislation, preferring tax cuts over funding the states.

Economic Woes

The stimulus package was a stopgap measure. After spending or allocating most of the federal funds, many states and localities still faced a dire financial situation. The federal government, running a huge budget deficit, was unlikely to give the states significant additional funding. As unemployment went up and people’s incomes went down, states’ tax collections decreased and their expenditures for unemployment benefits and health care increased. Many states had huge funding obligations, particularly for pensions they owed and would owe to state workers.

State governors and legislators, particularly Republicans, had promised in their election campaigns not to raise taxes. They relied on cutting costs. They reduced aid to local governments and cities. They fired some state employees, reduced pay and benefits for others, slashed services and programs (including welfare, recreation, and corrections), borrowed funds, and engaged in accounting maneuvers to mask debt.

At the University of California, for example, staff were put on furlough, which cut their pay by roughly 8 percent, teaching assistants were laid off, courses cut, library hours reduced, and recruitment of new faculty curtailed. Undergraduate fees (tuition) were increased by over 30 percent, provoking student protests and demonstrations.

At the local level, school districts’ budgets declined as they received less money from property taxes and from the states (about one quarter of all state spending goes to public schools). They fired teachers, hired few new ones (resulting in a horrendous job market for recent college graduates wanting to teach), enlarged classes, cut programs, shortened school hours, and closed schools.

Key Takeaways

The federal system functions, more or less, because of the authority of national over state laws, which trump local laws; crucial assistance provided by states and local governments to execute national policy; the complementary capacities of the three levels of government; and the intergovernmental lobby. The functioning of the system is being challenged by the economic woes faced by government at all levels. The Democratic and Republican parties differ ideologically about federalism, although these differences can be changed to achieve political objectives.

Exercises

- How do the perspectives of national, state, and local governments complement one another? What are the strengths of each perspective?

- Why do you think Democrats are more likely to prefer to make policy at the national level? Why are Republicans more likely to prefer to leave policymaking to state and local governments?

- How did conflicts between the national government and state and local governments contribute to damage caused by Hurricane Katrina? Why do you think federalism broke down in that case?

3.4 Federalism in the Information Age

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the media in covering federalism?

- How are some public officials in the federal system able to use the media to advance their political agendas?

- What effects could the new media have on people’s knowledge of and commitment to federalism?

Federalism gives the American political system additional complexity and dynamism. The number of governments involved in a wide sweep of issues creates many ways for people in politics to be heard. These processes are facilitated by a media system that resembles federalism by its own merging and mingling of national, state, and local content and audiences.

Media Interactions

National, state, and local news and entertainment outlets all depict federalism. Now they are joined by new technologies that communicate across geographical boundaries.

National News Outlets

News on network television, cable news channels, and public broadcasting is aimed at a national audience. A few newspapers are also national. Reporters for these national outlets are largely based in New York and Washington, DC, and in a smattering of bureaus here and there across the country.

Local News Outlets

Local television stations transmit the news programs of the national networks to which they are affiliated. They broadcast local news on their own news shows. These shows are not devoid of substance, although it is easy to make fun of them as vapid and delivered by airheads, like Will Ferrell’s character Ron Burgundy in the 2004 comic film Anchorman. But they have only scattered national and international coverage, and attention to local and state government policies and politics is overshadowed by stories about isolated incidents such as crimes, car chases, and fires.

Almost all newspapers are local. Stories from the wire services enable them to include national and international highlights and some state items in their news, but most of their news is local. As their staff shrinks, they increasingly defer to powerful official sources in city hall or the police station for the substance of news. The news media serving smaller communities are even more vulnerable to pressure from local officials for favorable coverage and from advertisers who want a “feel-good” context for their paid messages.

From National to Local

Local newspapers and television stations sometimes have their own correspondents in Washington, DC. They can add a local angle by soliciting information and quotes from home-state members of Congress. Or, pooling of resources lets local television broadcasts make it look as though they have sent a reporter to Washington; a single reporter can send a feed to many stations by ending with an anonymous, “Now back to you.”

From Local to National

Some local stories become prominent and gain saturation coverage in the national news. Examples are the shootings at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, in 1999; the murder of pregnant Laci Peterson in California on Christmas Eve 2002; the kidnapping in Utah of Elizabeth Smart in 2003; and the 2005 battle over the fate of the comatose Terri Schiavo in Florida. The cozy relationships of local officials and local reporters are dislodged when national reporters from the networks parachute inWhen national reporters come from the networks to cover a local event. to cover the event.

In 2011, federalism took center stage with the efforts of Republican governor Scott Walker of Wisconsin, and related steps by the Republican governors of Indiana and Ohio, to save funds by stripping most of the collective bargaining power of the state’s public employee unions. Stories reported on the proposed policies, Democratic legislators’ efforts to thwart them, and the workers’ and supporters’ sit-ins and demonstrations.

Such stories expand amid attention from local and national news outlets and discussion about their meaning and import. National, state, and local officials alike find they have to respond to the problems evoked by the dramatic event.Benjamin I. Page, Who Deliberates? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996).

State News and State Politics

Except for certain governors and attorneys general, the local media give little space in their news to state governments and their policies. One reason is that there are only a few truly statewide news outlets like New Hampshire’s Manchester UnionLeader or Iowa’s Des Moines Register. Another reason is that most state capitals are far from the state’s main metropolitan area. Examples such as Boston and Atlanta, where the state capital is the largest city, are unusual. The four largest states are more typical: their capitals (Sacramento, Austin, Tallahassee, and Albany) are far (and in separate media markets) from Los Angeles, Houston, Miami, and New York City.

Capital cities’ local news outlets do give emphasis to state government. But those cities are relatively small, so that news about state government usually goes to people involved with state government more than to the public in the state as a whole.

State officials do not always mind the lack of scrutiny of state government. It allows some of them to get their views into the media. Governors, for example, have full-time press officers as key advisors and routinely give interviews and hold news conferences. According to governors’ press secretaries, their press releases are often printed word-for-word across the state; and the governors also gain positive coverage when they travel to other cities for press events such as signing legislation.Charles Layton and Jennifer Dorroh, “Sad State,” American Journalism Review, June 2002, http://www.ajr.org/article_printable.asp?id=2562.

Media Consequences

The variety and range of national and local media offer opportunities for people in politics to gain leverage and influence. National policymakers, notably the president, use national news and entertainment media to reach a national public. But because local news media serve as a more unfiltered and thus less critical conduit to the public, they also seek and obtain positive publicity from them.

State governors and big-city mayors, especially when they have few formal powers or when they face a state legislature or city council filled with opponents, can parlay favorable media attention into political power.This section draws from Thad L. Beyle and Lynn R. Muchmore, eds., “The Governor and the Public,” in Being Governor: The View from the Office (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1983), 52–66; Alan Rosenthal, Governors and Legislatures: Contending Powers (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 1990), 24–27; and Phyllis Kaniss, Making Local News (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), chap. 6. At best, a governor (as one wrote in the 1960s) “sets the agenda for public debate; frames the issues; decides the timing; and can blanket the state with good ideas by using access to the mass media.”Former governor of North Carolina, Terry Sanford, Storm over the States (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967), 184–85, quoted in Thad L. Beyle and Lynn R. Muchmore, eds., “The Governor and the Public,” in Being Governor: The View from the Office (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1983), 52.

Some state attorneys general are particularly adept and adroit at attracting positive media coverage through the causes they pursue, the (sometimes) outrageous accusations they announce, and the people they prosecute. One result is to put intolerable pressure on their targets to settle before trial. Another is reams of favorable publicity that they can parlay into a successful campaign for higher office, as Eliot Spitzer did in becoming governor of New York in 2006, and Andrew Cuomo in 2010.

But to live by the media sword is sometimes to die by it, as Governor Spitzer discovered when the media indulged in a feeding frenzyOften excessive coverage by the media of every aspect of a story. of stories about his engaging the services of prostitutes. He resigned from office in disgrace in March 2008. (See the documentary Client 9, listed in our “Recommended Viewing.”) Indeed, news attention can be unwanted and destructive. After he was arrested in December 2008 for corruption, the widespread negative coverage Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich received in the national, state, and local media contributed to his speedy impeachment and removal from office by the state legislature the next month.

The media are also important because officials are news consumers in their own right. State legislators value news exposure to communicate to other legislators, the governor, and interest groups and to set the policy agenda.Christopher A. Cooper, “Media Tactics in the State Legislature,” State Politics and Policy Quarterly 2 (2002): 353–71. Thus legislative staffers in Illinois conclude that news coverage is a better indicator of public opinion than polls.Susan Herbst, Reading Public Opinion: How Political Actors View the Democratic Process (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), chap. 2. The news may more heavily and quickly influence officials’ views of problems and policy issues than the public’s.

New Media and Federalism

New technologies that enable far-flung individuals quickly to obtain news from many locales can help people understand the many dimensions of federalism. People in politics in one state can, with a few keystrokes, find out how an issue is being dealt with in all fifty states, thus providing a boost for ideas and issues to travel more quickly than ever across state lines. The National Conference of State Legislatures, as part of its mission to “offer a variety of services to help lawmakers tailor policies that will work for their state and their constituents,” maintains a website, http://www.ncsl.org, with a motto “Where Policy Clicks!” allowing web surfers to search the latest information from a whole range of states about “state and federal issues A to Z.”

But new media create a challenge for federalism. They erode the once-close connection of media to geographically defined communities. Consumers can tune in to distant satellite and cable outlets as easily as local television stations. Cell phones make it as convenient (and cheap) to call across the country as across the street. The Internet and the web, with their listservs, websites, weblogs, chat rooms, and podcasts, permit ready and ongoing connections to groups and communities that can displace individuals’ commitment to and involvement in their physical surroundings.

In one sense, new technologies simply speed up a development launched in the 1960s, when, as one scholar writes, “one type of group—the place-based group that federalism had honored—yielded to groups otherwise defined, as by race, age, disability, or orientation to an issue or cause.”Martha Derthick, Keeping the Compound Republic: Essays on American Federalism (Washington, DC: Brookings, 2001), 152.

Yet the vitality of state and local governments, presenting so many opportunities for people in politics to intervene, reminds us that federalism is not about to wither and die. In the end, the new technologies may enable individuals and groups more efficiently to manage the potentially overwhelming amount of information about what is going on in policymaking—and to navigate quickly and adroitly the dazzling and bemusing complexity of American federalism.

Key Takeaways

The US media system blends national, state, and local outlets. Issues and stories move from one level to another. This enables people in politics to gain influence but can undermine them. New media technologies, fostering quick communication across vast expanses, allows people to learn and understand more about federalism but challenge federalism’s geographical foundation. Federalism seems like a daunting obstacle course, but it also opens up many opportunities for political action.

Exercises

- How do the perspectives of the national and local media differ? Why is there relatively little coverage of state politics in the national and local media?

- Do you get any of your news from new media? How does such news differ from the news you get from the traditional media?

Civic Education

Michael Barker versus the School Board

As Hamilton predicted in Federalist No. 28, if the people are frustrated at one level of government, they can make their voice heard and win policy battles at another. Federalism looks like a daunting obstacle course, yet it opens up a vast array of opportunities for political action.

Michael Barker did not set out to push the Louisiana state legislature for a new law. In 2003, Barker, a seventeen-year-old high school junior from the town of Jena, had wondered if his school district might save money on computer equipment by making smarter purchases. He sent four letters to the LaSalle Parish School Board requesting information about computer expenditures. He was rebuffed by the superintendent of schools, who notified him that a state law allowed public officials to deny requests for public records from anyone under the age of eighteen.

Barker did not understand why minors—including student journalists—had no right to access public information. Stymied locally, he aimed at the state government. He conducted an Internet search and discovered a statewide nonprofit organization, the Public Affairs Research Council (PAR), that promotes public access. Barker contacted PAR, which helped him develop a strategy to research the issue thoroughly and contact Jena’s state representative, Democrat Thomas Wright. Wright agreed to introduce House Bill 492 to strike the “age of majority” provision from the books. Barker testified in the state capital of Baton Rouge at legislative hearings on behalf of the bill, saying, “Our education system strives daily to improve upon people’s involvement in the democratic process. This bill would allow young people all over the state of Louisiana to be involved with the day-to-day operations of our state government.”

But Barker’s crusade had just begun. A state senator who had a personal beef with Representative Wright tried to block passage of the bill. Barker contacted a newspaper reporter who wrote a story about the controversy. The ensuing media spotlight caused the opposition to back down. After the bill was passed and signed into law by Governor Kathleen Blanco, Barker set up a website to share his experiences and to provide advice to young people who want to influence government.This information comes from Jan Moller, “Teen’s Curiosity Spurs Open-Records Bill,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, April 14, 2004; and Wendy Scahetzel Lesko, “Teen Changes Open-Records Law,” Youth Activism Project, E-News, July 2004, http://www.youthactivism.com/newsletter-archives/YA-July04.html.

3.5 Recommended Reading

Berman, David R. Local Government and the States: Autonomy, Politics, and Policy. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2003. An overview of the relationship between state and local governments.

Derthick, Martha. Keeping the Compound Republic: Essays on American Federalism. Washington, DC: Brookings, 2001. A set of discerning essays on intergovernmental relations.

Kaniss, Phyllis. Making Local News. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991. A pathbreaking account of how politicians and journalists interact to produce local news.

Lawrence, Regina G. The Politics of Force: Media and the Construction of Police Brutality. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000. An eye-opening example of how local issues do and do not spread to national news and politics.

Peterson, Paul E. The Price of Federalism. Washington, DC: Brookings, 1995. An astute assessment of the contributions that national, state, and local levels can and do make to government.

Posner, Paul L. The Politics of Unfunded Mandates: Whither Federalism? Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1998. A concise account of the ups and downs of unfunded mandates.

Shapiro, David L. Federalism: A Dialogue. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1995. A distinguished legal scholar debates with himself on the pros and cons of federalism.

3.6 Recommended Viewing

Amistad (1997). This Steven Spielberg dramatization of the legal aftermath of a revolt on a slave ship examines interactions between local, state, national, and international law.

Anchorman (2004). This vehicle for comedian Will Ferrell, set in the 1970s, spoofs the vapidity of local television news.

Bonnie and Clyde (1967). Small-time criminals become romanticized rebels in this famous revisionist take on the expansion of national authority against crime in the 1930s.

Cadillac Desert (1997). A four-part documentary about the politics of water across state lines in the American West.

Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer (2010). Alex Gibney’s interviews-based documentary about the interweaving of hubris, politics, enemies, prostitution, the FBI, and the media.

The FBI Story (1959). James Stewart stars in a dramatized version of the Bureau’s authorized history, closely overseen by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover.

First Blood (1982). When Vietnam vet John Rambo clashes with a monomaniacal local sheriff in this first “Rambo” movie, it takes everyone from the state troopers, the National Guard, and his old special forces colonel to rein him in.

George Wallace: Settin’ the Woods on Fire (2000). A compelling documentary on the political transformations of the Alabama governor who championed states’ rights in the 1960s.

Mystic River (2003). A state police officer investigating the murder of the daughter of a childhood friend faces “the law of the street” in a working-class Boston neighborhood.